Zuzana Chovanec

Poppies and Women Under the Linden Tree in a Slovak Village:

Exploring Culturally Significant Plants Through Informed Archaeological Storytelling

ABSTRACT

In her 1993 book, What This Awl Means, Jane Spector examined the relationship between gender, objects, environment and archaeology through a female personal narrative. While such historical storytelling has been viewed as unconventional, it is effective as it paints a vibrant picture communicating context, significance and insight into what might otherwise be viewed in traditional archaeological description as a simple, utilitarian tool. However, to do this effectively, sufficient cultural competence and symbolic understanding must be woven with archaeological research, anthropological interpretation and understanding of the cultural and historical context through the lens of storytelling. This paper explores this approach by presenting the complex symbolic and agroeconomic relationships maintained with the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum L.) and the linden tree (Tilia spp.) by ancient peoples in Central Europe. The story draws on a body of archaeological, botanical and chemical research, Slovak cultural and linguistic background, as well as ancestral oral history.

Keywords

storytelling, plants, poppies, linden tree, archaeology, Slovak.

ntroduction

ntroduction

A story is connected to many elements, including the relationship of the storyteller to the story that is woven. As the teller of this story, I draw from my research as an archaeologist working on various aspects of the environmental history of the opium poppy, with data collected as a Fulbright scholar in the Slovak Republic (2018–19), but also many years of accumulated cultural knowledge from my own experiences, having been born in the Slovak city of Trnava, and ancestral oral traditions covering multiple generations. My work is also informed by research on Indigenous storytelling and environmental relationships, to which I was introduced through my experiences in North American archaeology over the last decade and related engagement with Tribal Nations in historic preservation contexts.

The lost art of storytelling in archaeology

Stories are, in principle, at the centre of what archaeologists do – namely, unraveling the lifeways of past peoples through the ordered examination and analysis of the material remains left behind.1 The nature of those stories depends largely on the hands weaving these remaining threads. Maggio notes that there is some focus on storytelling as a domain within anthropology, but this tends to be more about individuals telling stories of experience and the relationship of the storyteller to listeners, story characters and events. The resulting narrative is predominantly analytical, rather than utilising storytelling as a research method or mode of communicating results.2 Such analytical writing often takes the form of what Pluciennik terms diktat, where archaeologists view themselves as experts weaving authoritative and objective narratives that they are uniquely qualified to write.3 This is unfortunate because, in almost every domain, storytelling informs the human aspect of our lives.

The stories told in archaeology have changed over time. In the foundational years, stories meant fanciful tales of princes and princesses and presumptions about the past that said more about the predominantly Western European men writing them than the lives represented in patterns of material culture remnants. Over the years, archaeology firmly articulated its methods of investigation and diversified modes of interpretation by engaging with various anthropological models. Regarding gendered perspectives, the entry of women into the field initiated changes in archaeological narratives – inserting women, children, people of colour, those crossing gender categories, and numerous other voices into an archaeological record previously only inhabited by men as primary actors.4

Thus, the character of the academic narrative also changed, towards Pluciennik’s5 demotic voice, which presents archaeologists as ‘mediators and facilitators’ in a conversation about the past that includes many voices. This approach accepts the ‘responsibility of archaeologists as authors’6 and that archaeological data represents a subset of a lived reality. Those working in ethnoarchaeological perspectives and in consultation with descent communities may more readily appreciate the potential misinterpretations of their datasets.

Day acknowledged that the ‘linear, written, expository’ archaeology narrative does not reflect how human beings experience life and as such ‘experimental narratives’ transform ‘the two-dimensional world of data… into the multidimensional world of sensory life’. 7 But are these necessarily stories?

Ranco and Haverkamp state in regard to Indigenous storytelling that ‘[w]ithout stories, we have no way of connecting what it means to be human with the pathway of our existence’ and that stories are ‘central to knowing, learning, and teaching about the world and reality’. 8 In this sense, stories serve as the lens through which we comprehend our surroundings, as well as other living creatures inhabiting it.

The terms narratives, stories and storytelling require some distinction. Grötsch and Palmberger note that ‘narratives give meaning to events and experiences’,9 while Bruner differentiates between ‘landscape[s] of action’ and ‘landscape[s] of consciousness’, wherein one addresses events and the other how they are experienced and perceived.10 These landscapes are ultimately ‘intertwined’ through the story.11 However, the distinctions soon blur into synonyms and analytical treatment as mere indications of cultural thinking and values. Boas and Malinowski acknowledged as much a century ago in recognising oral traditions as a touchstone for understanding other cultural elements.12

Nothing stated here should be taken to suggest that such archaeological storytelling lacks rigour, principles or methods. Successful archaeological storytelling requires parameters, such as those espoused by ethnoarchaeological approaches, the goal of which is to better understand ‘how ancient societies functioned day-to-day’ from archaeological remains.13 In London’s work on pottery production in Cyprus and the eastern Mediterranean, it quickly becomes clear how arbitrary interpretative categories that well-meaning archaeologists unknowingly superimpose on their subjects may be. In reality, people had far ‘more fluid lifestyles and workplaces’.14

Storytelling and communicating research

Who tells the story makes a difference. Van Dyke and Bernbeck15 rightly suggest limitations for outsider archaeologists (i.e., Western European, American, or others where colonial or imperial legacies have privileged their positions) in writing fictionalised accounts of ancient individuals that purport to give the said individual(s) a voice. This need not apply to all, as a greater number of anthropologists and archaeologists are working in their own communities, protecting their own heritage and writing histories from their own perspectives. It is acknowledged that archaeology as a scientific discipline must be explicit about its methods, data and interpretative schemes, and, thus, storying cannot replace other modes of research dissemination. Pollack, who makes an important point in a field where popularised misinformation can reign, emphasises that such creative presentations must explicitly connect to archaeological data.16 However, as recent critiques of the discipline’s history have shown, new perspectives are needed.

The story presented by Phillip Tuwaleststiwa (Hopi) and Judy Tuwaleststiwa is instructive. Their work, which uses imagery from diverse points in history, represents an accumulation of cultural understanding, with the resulting story carrying ‘much truth as fiction’ ‘to the Native eye and ear’.17 Such a perspective is invaluable; but outsider archaeologists can also take steps to account for such differences (e.g., Van Dyke making sources explicit and Jane Spector’s extensive collaboration with descent community members).18

Returning to the needed distinction between story and narrative, Phillips and Bunda aptly characterise storying ‘as an act of making and remaking meaning through stories’, which are ‘alive and in constant fluidity as we story with them’. 19 They rightly view ‘humans as storying beings’ wherein ‘telling stories is a natural human habit’.20 Why should the presentation of ancient human lives through archaeological data be any different? More recent focus on oral traditions demonstrates they act as great repositories of cultural information, capable of communicating complex, interrelated themes in the form that our human brains are best equipped to process. Thus, ‘[s]torytelling reveals meaning without the error of defining it’.21 There is much to be learned from listening to these voices in their own right,22 but also in how the relationships between ecological knowledge, cultural understanding and intergenerational communication are approached and understood. The significant role that storytelling holds for multigenerational women is further acknowledged, as well as how it functions to encapsulate and transmit cultural and technical knowledge.23

Women as transmitters of knowledge

The domains traditionally inhabited by women as holders and transferers of knowledge interface with the ecological, religious and economic. Montanari and Bergh illustrate how women’s traditional knowledge transforms product development.24 Kelly and Ardren25 further relay archaeological case studies wherein women’s traditional knowledge covers various domains (culinary, ethno-medicinal, agricultural, etc.) and forms ‘an integral part of the women’s contribution to the daily sustenance and maintenance of the household’.26 This should not, however, be taken as a simple statement about domestic work, but as fundamental and critical work in which women are actors, directing not only the perpetuation of crucial knowledge systems in complex social pathways, but also decision-making that ensures the health and prosperity of the social system at multiple levels.

As ‘knowledge and use of … plants are concentrated among women because of their role as managers of household health’, Reyes-Garcia27 shows that such knowledge is distributed based on a series of variables (e.g., kinship, age, degree of specialisation) and transmitted through social network relationships. For example, information may be transmitted vertically (e.g., from parent to child), horizontally (between ‘two individuals of the same generation’), or through oblique, but nonvertical transmission (from parental to filial generation, but not a parent to child).28

Storytelling is often the mechanism through which such information is transmitted and within the domain of women. According to Phillips and Bunda, ‘[w]omen were always the story-givers, the memory-keepers, the dreamers’, with the transgenerational transfer of ‘grandmothering stories’ serving to ‘connect womenhood across time, culture, and place’.29

Plants as actors

There may also be other nonhuman actors in such storytelling, including plants. In such scenarios, not only are the stories different, but the characters taking the central role may also be so. Middlehoff and Peselmann30 highlight not only the myriad ways in which plants interweave themselves in human lives, but also how they enter the narratives that humans weave about themselves. Those that observe and understand the individual, communal and temporal relationships plants have with both vegetal and non-vegetal co-inhabitants within an ecosystem perspective come to realise the value of other explanatory models (i.e., traditional ecological knowledge systems). Myers stated that ‘more than the sciences [was needed] to engage in meaningful encounters with plants’.31 These sentiments highlight the degree of separation and alienation from nature (as conceived by Tyburski)32 and the great desire to reinsert an ‘ecological consciousness’ into Western science.

Sensing plant stories requires so much unlearning … [of] approaches that alienate us from our more-than-human kin and render them as objects and resources… unlearning what we think sensing is, what we think communication is, what we think counts as a story…33

However, those coming from a cultural paradigm based on extraction and exploitation must take care not to focus this desire into an appropriation from ‘eco-cultures’ that have maintained their connections to nature.34 Such examples can readily be seen in the popularised search for secret Indigenous knowledge from psychoactive plants and the assumption of Indigenous practices, like smudging.35 Tsymbalyuk likewise highlights not only a similar ‘resourcification’ of the Russian war on Ukraine, but also the significant role that stories about plants have on the emotional connections of places – destroyed or forcibly abandoned – to the extent that ‘the connections to plants in those landscapes are synonymous with conceptions of home, self, and being’.36

In the context of storying practices, plants may serve as actors and tell us about themselves at three levels: a plant’s lifecycle, that of a plant community (i.e., forest, field, garden) and individual plant lives.37 Such levels are represented in the story below with different types of plants whose lifecycle extends on vastly different time scales, individual plants (i.e., individual trees), and communities of plants (i.e., poppy fields and treestands). As discussed later, the story serves as a repository of knowledge – drawing from fifteen years of archaeological research from various viewpoints (botanical, chemical, archaeological, culinary, etc.), accumulated cultural knowledge, and ancestral oral traditions – presented in a format that is equally accessible to readers (or listeners) across diverse domains. Complex interrelated themes, histories and information are communicated in a simplified form that humans – as storying beings – understand best.

STORY: Poppies, pins and women under a Slovak tree grove

Figure 1.

Poppies in bloom, Podbanské, Slovakia, 2021 (left); dried poppies in field, Zuberec, Museum of the Orava Village, Slovakia, 2023 (right).

Source: courtesy of Alena Chovanec.

Our village is one of several within a broad valley that is nestled in the forested foothills of two low mountain ranges and made fertile by the streams that descend from them. At the end of spring, the gardens of our village were set ablaze with the vibrant colour of our poppy crop, standing tall and proud, swaying in the wind as it rolled through the valley.

One of the happiest times when I was a girl would happen a few months later, when the poppies were dried, piled up and carried to the courtyard of our family’s compound. It was here that the women of my family – my mother, grandmother and sisters – would sit in a circle talking – telling stories of our village, family and how our people came here and established our village generations ago, stories of brave heroes that once fought against invaders, of young girls seeking shelter under the linden tree in the sacred woods of the surrounding hills that still remained at the edge of the valley, and children’s stories where mountains, flowers, trees and mushrooms came alive.

The memories of these simpler times of my life in my family’s house bring me joy, though they now seem a lifetime away, as I walk in silence alongside the other high-status women of my husband’s family. The men trot their horses before us to the neighbouring village for the summer festival.

My clothes are now made of the finest flax. Grown and harvested by men like my father and grandfather, who later stacked it to dry in little piles across the hills. Later it was spun by women not unlike my sisters – all of whom live on the lower road of our village – where I rarely get the occasion to travel freely these days. My sleeves are layered and adorned with the age-old designs of my village foremothers; my hair is parted, wrapped and braided with summer flowers, and my neck and arms laden with metal spiraling bands. My ceremonial dress is affixed with metal pins extending from the breast of my dress up beyond my shoulders. They are long, like that of a poppy stalk and their carefully fashioned heads are globular like that of a dried poppy capsule top.

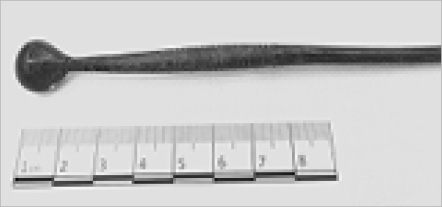

Figure 2.

Copper pin, Malá Vieska type*, measuring 44 cm in length, head of pin, 1.3 cm diameter. A1983.

Source: photograph by author with permission of the Balneologické Múzeum V Piešťanoch, Pieštany, Slovakia, 2019.

Note: * The Malá Vieska type of copper pin is longer than many other types of pins, which may measure between 40 cm to well over metre in length. The example discussed here represents a shorter version. See Novotná Die Nadeln in der Slowakei for detailed catalogue.

These metal ornaments reflect my husband’s stature. They are fine, but heavy, making the miles we are to walk to the celebration in the neighbouring village far more arduous than it once was. We walk the lower road, where I spent my childhood and past my father’s compound. I longed to walk through the wooden doorway and take one more look through the courtyard where I spent my younger, carefree days.

The swaying poppy flowers that coloured so many mornings of my youth had already passed. The petals had long blown away, and all that remained were the large, bloated capsules filled with blue seeds to make pastries filled with ground poppy seeds sweetened with my grandfather’s honey. The stalks were tall, rigid and dry, being collected into wooden wagons, which would soon be delivered into the compound courtyard, where the women of the household would sit for many hours. With their heavy skirts gathered, holding a weathered but still sharp knife, they would skillfully slice off the wheel on top of the capsule, and the lovely gray and blue seeds would be poured into the buckets between their feet. Typically, we would sit close to the animal pen or the outdoor hearth, where we would discard the stalks and empty pods that would be later burned or composted with other trash.

They were difficult but happy times, narrated by the songs that women in our village had sung for generations before ours, filling the hills with music, as they toiled in the fields. My favourite when I was a girl was the song about the little finch and how the poppy is sown, grows, flowers and is eaten. These flowers and seeds always seemed to follow me through the happy and difficult times of my life. They sweetened my meals and nourished me when meat was scarce.

By this time, the dried poppies would fall apart almost as soon as the seeds left their casing. But occasionally there was an especially large, or lovely capsule, that would be kept in its entirety, to remind us of the blessings of the summer and keep away the unruly spirits that roamed the changes of seasons. These my aunts would save and place in vases or weave into wreaths at the end of the summer, which would later be placed to guard our windows or doors.

In the years when the great sickness swept through the villages, I learned how the smaller, more shriveled capsules could be soaked in a tea made from the mountain herbs to be given to the little ones when their fevers raged through sleepless nights. It brought my little cousin some brief comfort as I sang to and cradled him close just before the morning light – before he like many others in the village succumbed to the great god. It still weighs on my heart to think of when we laid his frail little body to rest with all the other faces I had once known. Now it is only those few of us who remain that know what lies beneath the unmarked, barren ground in the empty space at the entry way of the cemetery. In following summers, I used to make a little man or wagon out of the dried chaff and leave it on the stone wall to let him know I still think of him.38

My fingers slowly touched the long metal ornament binding the layers of embroidered cloth, running down from each of my shoulders. They were long and fashioned to appear as the tall, proud poppies, and were in fact nearly as long as the poppy stalks. The poppies no longer dotted the margins of the fields, but I always carried their significance with me in this way.

Years later when the people from the east came, I would carefully shed my fine clothes and metal adornments, along with those that my daughters and their cousins had worn. We bound them together and wrapped them in our layered garments, before burying them. This was not the only time my people buried metal objects; the men would likewise bury objects made of our valuable metal axes and spearheads at strategic paths along their journeys. The burial of our pins differed from their more practical means.

We women removed our pins, carefully bent the bottoms to close their spiritual paths, bound them with items of each of our clothes and buried them on the south side of the hill overlooking our valley.39 We laid them in the shade of the linden trees in the primordial forests, where stories resounded of my ancestors who revered these ancient trees. As a child I only knew them as the source of the flowers that we used for tea in the winter. When I became a woman, I learned that they held much greater power and significance for us – like the poppy that had followed me through the ups and downs of my life, that we looked to for wishes of protection and prosperity and new beginnings. We only went to the linden in greater times of need. As we have for generations before, we return to these sacred woods; so now it seems fitting to take the symbol that led and nourished me through my life thus far and entrust it to these trees so that the women our village may be protected from dangers that come from across the eastern mountains. And so, we bury these great symbols, born of our fields, products of the mountains, and moulded by fire, we lay them here, bind them with the fruits of our labour, that they may protect us as we move further west.

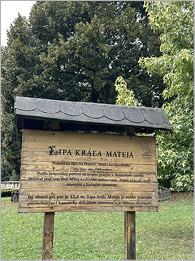

Figure 3.

Gabriela Čechovičova harvesting and selling poppy seed in Cifer, Slovakia.

Source: Alena Chovanec, 2021.

Figure 4.

Dried, halved poppy capsules in wreaths and dried poppy stalks on display.

Source: Author, 2018, Trnava, Slovakia.

Poppies in the field

As much of the above centres around the imagery and symbolism of the opium poppy, a brief introduction to the plant’s characteristics and significance follows. The opium poppy, Papaver somniferum L., is a plant with which human beings have maintained a long and complex relationship. The plant has four-petaled flowers that vary in color, a capsule-like fruit that produces many seeds and a white juice (latex) that produces numerous pharmacologically active chemical compounds, found in the exterior of the capsule40 (see Figure 1). It serves both as a highly nutritious food and one of the most widely used psychoactive and medicinal substances.41 These features make it a multipurpose plant in a genus (Papaver) with various members.

The white juice in the outer skin of the capsule serves as a defensive mechanism against predators that would injure the capsule to get to the seeds inside. It contains over forty alkaloids, in five different classes, including morphine, the most abundant. The concentrations of alkaloids may differ based on plant development and environmental factors. Together, the product opium is highly addictive but also has a wide range of medicinal applications. Excessive doses result in nausea, convulsions or death.42 As such, the opium poppy and its alkaloids are at the centre of the global opioid crisis. Public concerns about opium addiction are not a modern phenomenon, with large scale addiction documented in the nineteenth century, as evidenced by a range of tonics with opium as an ingredient, public criticism of opium addiction in nineteenth century news articles, and the well-known account of an English self-professed opium-eater.43

Despite this history, the opium poppy in Central Europe was traditionally utilised as an edible plant, which corroborates much of the archaeobotanical data.44 It may be noted that Sovičová classifies the opium poppy in a list of poisonous plants.45 Those from East and Central Europe are keenly aware of the number of food items produced from poppy seeds and that the poppy seeds and the alkaloid-rich opium are synthesised and harvested from different parts of the plant in different ways.46 The seeds are obtained from inside the poppy capsule and may be harvested when the seeds inside the capsule sound like a child’s rattle. Depending on the point of harvest, different varieties (blue, gray, white, etc.) have different flavour profiles47 (see Figure 3). Opium derives from within the exterior coat of the poppy capsule and functions botanically as a defensive mechanism, to protect the seeds inside the capsule.48

Direct and indirect archaeological and historical evidence for the knowledge of the opium poppy occurs throughout the Mediterranean Basin, Europe and beyond. The nature of evidence includes preserved macrobotanical remains (seeds and capsules), microbotanical remains (pollen and phytoliths), chemical residues, literary references and a broader body of suggestive evidence for the knowledge of and a symbolic association with the opium poppy’s psychoactive and soporific (sleep inducing properties). In Central Europe, remains of poppy were first encountered in the nineteenth century in the context of Neolithic pile-dweller villages around the banks of Swiss lakes, which had extraordinary preservation of organic remains. There is some evidence for poppy species in modern-day Slovakia in these earlier periods, but it is not until the Bronze Age that it appears in notable amounts, reaching high levels of cultivation in the Medieval period. The remains most often are found within food storage contexts, and almost exclusively in the form of seeds.49

The nutritional value of poppy seeds is significant, largely due to their high oil content. This oil, which has a long shelf-life, contains various vitamins and minerals. It is especially high in Vitamin E and the essential fatty acid linoleic acid, which is key to growth and development. Safflower (Carthamus tinctorius) is the only other plant oil that is higher in linoleic acid.50 Olive oil, one of the key edible and industrial oils of ancient times, is high in oleic acid, but relatively low in linoleic.51 The benefits of poppy seed oil have received greater attention in recent years.52

Delineating the early history of the opium poppy and its use by humans is complicated in that it’s a weedy species that readily invades disturbed soils. Differentiating the small seeds to the species level can be difficult. This is necessary to determine if and how the remains were used by ancient humans.53

There are significant cultural and symbolic associations with the plant, particularly in the Slavic world where its use as a culinary product is widespread and it is a frequent element in folklore.54 Far too often the narcotic and medicinal uses of the opium poppy are overemphasised whereas its importance in subsistence and symbolic culture overlooked, as is its embeddedness within the broader environmental, social, economic and cultural framework. Interwoven in this framework are relationships with other actors, such as the people who grow, process and use the poppies and their products, other plants with which the poppy shares an ecological landscape (i.e., hemp and flax) and the stories, songs and rituals – both large and small – that communicate their meaning intergenerationally.

The opium poppy, role of women and storytelling in Slovak cultural context

Several important themes pertaining to the poppy are illustrated in the story. The first is that, for Central European Slavic people and Slovak people especially, the opium poppy is an agricultural product, used for its seeds and oil, having a special role in culinary culture, signifying wealth and prosperity, health and goodness,55 but also having broader symbolic associations with the plant’s soporific properties.56

As noted above, there is a greater research focus on the psychoactive characteristics of the plant and its use by humans than on its agricultural history (and prehistory). The archaeological, botanical and historical evidence for much of the opium poppy’s history has largely been agricultural in nature, though the plant’s role as medicine, narcotic and poison cannot be overlooked either.

In that regard, this story examines the spatial, ecological and social relationships involved in the cultivation of poppy, including conditions under which it is sown, harvested and used, who does this work and how, and other key plants with which the poppy has a relationship, particularly flax (Linum usitatissimum). The story likewise highlights a knowledge of the ‘poppy tea’ traditionally used to help children sleep,57 while making it clear that the extraction of opium from the plant was not how it was used in this cultural context.

A number of details derive from personal and family experiences, locations and oral histories, including the relationship among multigenerational women within the same extended family, and their role in society and household production. In this regard, the story should not be viewed as one that occurred at a particular historical time or place, which is a key characteristic of novelistic tales in the Slovak tradition58 (as well as the Hopi story above). In such tales, time and place remain undefined, and they tend to be situated in Slovak towns, and focus on ‘everyday life of a common person’.59 More specifically, ‘novelistic tales reflect social reality’, depicting rituals, with ‘material culture also work[ing] its way in’.60

Today’s corpus of Slovak folktales was collected in the nineteenth century by Pavol Dobšinský, Ján Botto and other Slovaks in the generation of Ľudovit Štúr, who codified a formal literary Slovak language.61 One belief, in collecting these tales, was that, inasmuch as the wondertales may reflect ‘events of the ancient past, only symbolically’,62 in examining their content and the themes held therein ‘“we would see the entire science of our forebearers about the gods, the creation and the order of the earth”’.63 This is not vastly dissimilar from the role of storying as taken up by Phillips and Bunda.64 Zipes emphasises that ‘fairytales are rooted in oral traditions’, ‘were never given titles, nor did they exist in’ their modern forms.65 Thus, there is a malleability or dialogic character between the tales and the cultural themes to which they relate. Further, not only do the tales ‘contribute to our storying selves but [they] also weave the threads of social relationships and make life social’.66

In that regard, themes of space, in the organisation of village life, but likewise in the distance of social space experienced by married women, are important elements to the story and in a sense ensure the reader is aware of that traditional societal norms and hierarchical divisions are at play, while acknowledging the significant role that female kinship played in the maintenance of various types of cultural knowledge. Other cultural elements, that again reconnect with archaeological and historical elements, relate to the production of fine cloth from the finer flax thread and the use of fine metal adornments that simultaneously highlight elements of the historical kroj – traditional, ethnic clothes the designs of which were highly localised. This is also reference to the long metal pins that would have served as adornments similar to those used in the Bronze Age.67 Novotná and Kvietok suggested that this pin type, taken together in its shape, dimensions and decoration, signified the opium poppy68 (see Figures 1 and 2 for comparison). The symbol of the poppy, representing wealth, prosperity, goodness and health, would fit this context well.

The poppy was decorative in other contexts, being saved and used for wreaths which served a protective function at crucial times of year (see Figure 4). It appears in songs (e.g., Čižiček, čižiček, vtáčik maličký), modern stories (Maková Panenka, Poppy Fairy), and other versions of well-known fairy tales. An example of the latter comes from Cinderella (Popoluška). As many familiar with the tale know, our heroine is given menial tasks to fill her time so that she is unable to get ready for the ball, but, in the Slovak version, the task she is given is to separate poppy seeds from ashes.69

Future story events and the significance of the linden tree (Lipa)

Future events are recalled in the story, namely the burial and ‘killing’ of the pins by bending them, which references metal hoards of bound Bronze Age metal pins within forested areas, well documented in the Bronze and Iron Ages, as well as in the Celtic world.70 These events are accompanied by another important cultural plant – the linden tree (Lipa in Slovak). The relationship to the linden is a key aspect of the story, not only in terms of the relationships that plants have with other human and nonhuman entities, but also because it has very specific cultural connotations. Slavic cultures, including but particularly Slovaks, adopted the linden as a cultural symbol (see discussion below).

Trees as symbols in human culture may mean many things. For Rival, a key symbol is that of perseverance, due to their permanence in our surroundings and across human lives.71 Wohlleben brings our attention to the temporal differences between the lives of creatures, including human beings, and the lives of trees – as individuals as well as communities.72 It should be noted here that some of Wohlleben’s viewpoints are controversial in that the biological and ecological ‘actions’ of trees have yet to be demonstrated.73 However, Indigenous scholars, such as Robin Wall Kimmerer (Citizen Potawatomi Nation), may hold different perspectives about ascribing human characteristics to trees.74

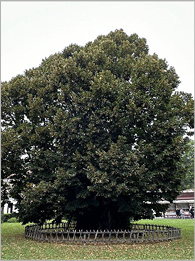

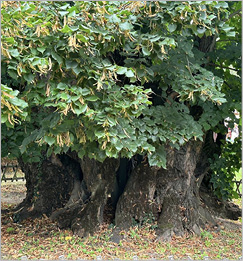

Regardless, the actions and reactions of trees are minimally visible to us and, as a result, trees represent permanent beings in our lives, our landscapes and generally our understanding of the world around us. For example, the oldest linden tree (large-leafed variety, Tilia platyphyllos) known in Slovakia is over 700 years old and sits within the grounds of the Bojnice Castle located in the town of Bojnice, in Trenčin region (see Figure 5). According to legend, the tree was planted by Matús Čák in 1301 to mark the occasion of the death of the last Arpad king, a Magyar dynasty that established itself after the conquest of the Carpathian Basin and consolidation of its tribes at the turn of the tenth century. The story above likewise alludes to these historical events wherein invaders come from the east, but the focus is more on cultural themes, relationships with symbolic plants and the role of these plants as co-inhabitants of these landscapes. The Bojnice linden is today a national monument.75 Another important tree is located near the Church of St Margita Antioch in Kopčany, overlooking the Great Moravian capital of Nitra. In 2019, the tree received sixth place in the European Tree of the Year contest.76

Figure 5.

The oldest linden tree in Slovakia at Bojnice Castle.

Source: Jan Chovanec, Bojnice, 2023.

The linden continued to play a significant role in more recent Slovak national history. When then Czechoslovakia first became a republic in 1918, the occasion was celebrated with the planting of a linden tree in the main square of Skalica – the linden of freedom (‘Lipa slobody’). Similarly, the planting of linden trees marked other important occasions in national history, clearly symbolising Slovak identity and perseverance, such as following the Velvet Revolution in 1989, and, indeed, a linden leaf is depicted on the Slovak Republic national seal.77

The story deliberately models the linden tree as a safe place, a place of refuge, associated with freedom, but also resistance, a symbol of Slovaks, safety and self. The tree, with its heart-shaped leaf, adorns many important entities in recent history, including the national seal and commemorative stamps, but it has had this connotation for hundreds of years, pre-dating Christianisation. In the first century bc, when Celtic tribes inhabited Slovakia, a coin depicts a king by the name Biatec riding a horse, holding tree branches with heart-shaped leaves, typical of the linden tree.78

Linden trees were incorporated into many parts of the Slovak cultural landscape; they were often planted by churches, at the entrances of villages, to mark important occasions.79 This is not dissimilar from the Osage Indians (Osage Nation) in the central United States planting trees, sometimes culturally-modified, to mark important places, water sources or crossings, and facing specific directions.80 The plants themselves are not inactive participants, with the actions of the tree hardly visible to rapid human lives, but moulding the intentions and actions of their co-habiting Slovak neighbours for centuries. This element of intra-species relationships explains the significance of stands of trees not only from an ecological perspective, but also as a locality where significant human events take place.

Sir James Frazer in his well-known compilation of cross-cultural religious practices shows a great interest in trees and their worship.81 However, Ronald Hutton importantly highlighted the series of ethnic biases and political agendas underlying many observations in the Golden Bough.82 For instance, in reference to the current topics, Frazer states, ‘[t]he heathen Slavs worshipped trees and groves’.83 While such observations are quite problematic, the comparative methods he applied still provide important insights and demonstrate a clear reverence that human beings have for trees with many examples of human-tree (and plant) relationships.84

We see elements of kinship and their incorporation into the cycle of human reproduction; a connection to the supernatural, and a means to influence agricultural productivity. Some examples include rituals involving trees for women desiring a child – and signs of whether their desires will be granted.85 Likewise, trees, including linden trees, were located in every yard, considered sacred, and ‘pregnant women clasped [them] to ensure easy delivery’.86 There are again references to flax, referenced in the story and in relationship to both the poppy and the linden. In an example from Germany, a ritual took place under seven lindens, in which a ‘grass king’ was stripped, crown removed, and branches were put in flax fields ‘in order to make the flax grow tall’.87 Elsewhere, linden bark was used for this purpose.88

There are clear, personal relationships with individual trees or communities of trees. In The Giving Tree, a modern story with which many readers may be familiar,89 we see an individual relationship with a specific tree but situated within a more contemporary tendency to see trees as ‘utilitarian sources for human life – providing wood, fruit, sap and shade’.90 This kinship also extended to the trees themselves: ‘The conception of trees and plants as animated beings naturally results in treating them as male and female, who can be married to each other in a real and not merely figurative or poetical sense of the world’.91

Such ideas are articulated in multiple storying traditions. Thus, these are the stories that plants tell if we listen to them.92 And the opium poppy and the linden tree tell the story of the Slovak people.

An informed archaeological storytelling

In terms of the utility of informed storytelling in archaeological narrative, Maggio highlights elements of storytelling in ethnography, where storytelling is an act and thus an ‘anthropology of storytelling should consider … everything that happens around it’.93 As demonstrated above, many elements are woven into the story – cultural, material, botanical, structural – that intersect in complex ways. An informed story not only presents the complexity of our tasks as archaeologists, but likewise ‘makes the reader [or hearer] empathise with the characters’, thereby creating a relatable connection, and achieving the goal of understanding and re-animating the fullness of what remains of lives lived long ago.94 Annabel argues that folktales simultaneously ‘must always be understood in [their] social-historical context’ but have ‘universal appeal because of the way [they] function’95 and, in that sense, there are always parameters required for an archaeological story of this sort.

In that sense, storytelling in archaeology can be an effective means for communicating the complex interplay of diverse sets of data that cross disciplines and vary in scope within the temporal scales unique to archaeological inquiry. Doing so within an informed story synthesises these data, presented in a format that connects data points to human experience and understanding, while also humanising the actions preserved in material remains – not only for readers of diverse backgrounds, but also as a much-needed reminder to the investigators themselves.

Conclusions

The goal of this paper was to use an informed storytelling framework that draws on historical and archaeological research, knowledge of significant cultural themes and related oral traditions to illustrate the dynamic and complex lives that ancient people, sometimes our ancestors, lived. From this perspective, a simple, but well-crafted, informed story, presents many themes interwoven in an approachable way to help us understand how different elements of the archaeological record work together. In the relating of this story, two culturally significant plants – the opium poppy and the linden tree – hold active and directing roles in the events, relationships and themes described. And thus, referencing Arthur Frank,96 it may well be the plants within these stories that breathe and animate our lives.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research underpinning the work presented here was supported by the US Fulbright Association (2018–2019). Recognition is given to the J.W. Fulbright Commission in the Slovak Republic, the Slovak Academy of Sciences in Nitra, the Agricultural Museum, the Nitra Museum, and the Balneology Museum, as well as Dr Matej Ruttkay, Dr Lucia Benediková, Dr Maria Hajnalová, Dr Vladimir Krupa and Dr Andrej Sabov for their research assistance, also to Dr Gloria London for planting the seed of archaeological storytelling. Special thanks to my parents – Jan and Alena Chovanec – for their support and for sharing founts of knowledge, as well as the many relations from generations past whose stories continue to be told to this day.

REFERENCES

Abrahámova, M. and G. Čechovičová. 2017. Maková knižka. Bratislava, Slovakia: iKAR.

Aggarwal, R. 2000. ‘Traversing lines of control: Feminist anthropology today’. Annals of the American Academy 571: 14–29.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716200571001002

Bátora, J. 2015. ‘Poherbiská a pohrebný rítus’. In Staré Slovensko: Doba Bronzová. Vol. 4. Nitra: Archeologický ústav SAV. pp. 117–24.

Bellan, Stano. 2019. ‘Stromy našich životov’. Skalický Obzor, 8 March. http://skalickyobzor.sk/cms/stromy-nasich-zivotov/ (accessed 23 August 2023).

Beranová, M. 2012. Jídlo a Pití. V Pravéku a ve Stredovéku. Praha: Academia.

Bernáth, J. 1998. ‘Utilization of poppy seed’. In J. Bernáth (ed.) Poppy. The Genus Papaver. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic. pp. 337–41.

British Museum. 2023. ‘Biatec’: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG194617 (accessed 20 August 2023).

Brück, J. 2016. ‘Hoards, fragmentation and exchange in the European Bronze Age’. In S. Hansen, D. Neumann and T. Vachta (eds), Raum, Gabe und Erinnerung. Weihgaben und Heiligtümer in prähistorischen und antiken Gesellschaten. Berlin: Edition Topoi. pp. 75–92.

Chovanec, Z. 2019. ‘Examining the history of the opium poppy in the Eastern Mediterranean and Europe’. Full Spectrum Communication. https://openarchem.com/2019/04/07/examining-the-history-of-the-opium-poppy-in-the-eastern-mediterranean-and-central-europe/ (accessed 10 April 2019).

Chovanec, Z. 2020. ‘Cracking the history of the olive: Differentiating olive oil and Mediterranean plant oils through organic residue analysis’. Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry 22 (1): 45–66. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5906722

Chovanec, Z. 2023. ‘Oil, seeds, and cultural symbols: An agricultural history of the opium poppy, Papaver somniferum L., in the Eastern Mediterranean and Central Europe in comparative perspective’. Agricultural History Society Annual Conference, Knoxville, TN, 10 June 2023.

Chovanec Z. and P. Flourentzos. 2021. ‘A review of opium poppy studies in Cyprus and the Eastern Mediterranean with new evidence from Iron Age Cyprus’. In Z. Chovanec and W. Crist (eds). All Things Cypriot: Studies on Ancient Environment, Technology, and Society in Honor of Stuart Swiny. Alexandria: American Society of Overseas Research. ARS 28. pp. 145–56.

Cooper, D.L. (ed., trans.). 2001. Traditional Slovak Folktales. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe, Inc.

De Quincey, T. 1885. Confessions of an Opium Eater. New York: John B. Alden.

Dever, W. 2022. ‘Women in archaeology and antiquity’. In J. Ebeling and L. Mazow (eds). Pursuit of Visibility: Essays in Archaeology, Ethnography, and Text in Honor of Beth Alpert Nakhai. Oxford, UK: Archaeopress Publishing, Ltd. pp. 182–89.

Ďuríčková, M. and L. Pavlovičová-Baková (eds). 1990. ‘Čižiček, čižiček, vtáčik maličký’. In Spievaj si, vtáčatko: Slovenské ľudové piesne deti male i väčšie. Bratislava, Slovakia: Mladé letá. p. 58.

Fejér, J. and I. Salamon. 2014. ‘Poppy (Papaver somniferum L.) as a special crop in the Slovakian history and culture’. Acta horticulturae 1036: 107–09.

https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2014.1036.11

Frank, A.W. 2010. Letting Stories Breathe: A Socio-Narratology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226260143.001.0001

Frazer, J.G. 1890. The Golden Bough: A Study in Comparative Religion. MacMillian and Co.: London.

Furmánek, V. 2015. ‘Kov’. In Staré Slovensko: Doba Bronzová. Vol. 4. Nitra: Archeologický ústav SAV. pp. 223–45.

Furmánek, V. 2015. ‘Hromadné nálezy kovových predmetov’. In Staré Slovensko: Doba Bronzová. Vol. 4. Nitra: Archeologický ústav SAV. pp. 288–89.

Furmánek, V. and V. Mitáš. 2015. ‘Poherbiská a pohrebný rítus’. In Staré Slovensko: Doba Bronzová. Vol. 4. Nitra: Archeologický ústav SAV. pp. 268–71.

Grötsch, B. and M. Palmberger. 2022. ‘Introduction. The nexus of anthropology and narrative: ethnographic encounters with storytelling practices’. Narrative Culture 9 (1): 1–22.

https://doi.org/10.1353/ncu.2022.0000

Hajnalová, M. 2012. Archeobotanika v dobej bronzovej na Slovensku. Nitra: Univerzita Konštantína Filozofická.

Hutton, R. 2023. ‘Sir James Frazer’. Shaking the Tree, Breaking the Bough: Frazer’s Golden Bough at 100 Virtual Conference. 10 February 2023.

Jurgová, O. and K. Kaššová. 2018. Mak na našom stole. Bratislava: Slovenské pedagogické nakladateľstvo.

Kapoor, L.D. 1995. Opium Poppy: Botany, Chemistry, and Pharmacology. Binghampton, NY: The Hawthorn Press, Inc.

Kelly, S.E. and T. Ardren (eds). 2016. Gendered Labor in Specialized Economies: Archaeological Perspectives on Female and Male Work. Boulder, Co. University Press of Colorado.

https://doi.org/10.5876/9781607324836

Lančaričová, A., M. Havrlentova, D. Muchová and A. Bednárová. 2016. ‘Oil content and fatty acids composition of poppy seeds cultivated in two localities in Slovakia’. Agriculture (Pol’nohospodárstvo) 62 (1): 19–27.

https://doi.org/10.1515/agri-2016-0003

London, G. 2022. ‘Ethnographic and ethnoarchaeological insights to interpret first-millennium BCE material culture’. In E. Pfoh (ed.) T&T Clark Handbook of Anthropology and the Hebrew Bible. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, Inc. pp. 97–128.

https://doi.org/10.5040/9780567704757.ch-005

Maggio, R. 2014. ‘The anthropology of storytelling and the storytelling of anthropology’. Journal of Comparative Research in Anthropology and Sociology 5 (2): 89–106.

Marcus, M.I. 1994. ‘Dressed to kill: Women and pins in early Iran’. The Oxford Art Journal 17 (2): 3–15.

https://doi.org/10.1093/oxartj/17.2.3

Marder, Michael. 2023. ‘A philosophy of stories plants tell’. Narrative Culture 10 (3): 189–205.

https://doi.org/10.1353/ncu.2023.a903844

Marec, J. 2009. Požehnaj tieto dary: Tradičná ľudová strava na Horných Kysuciach. Magma: Kysucké múzeum v Čadci, Slovak Republic.

Merlin, M.D. 1984. On the Trail of the Ancient Opium Poppy. Cranbury, NJ: Associated University Press, Inc.

Middelhoff, F. and A. Peselmann. 2023. ‘The stories plants tell: An introduction to vegetal narrative cultures’. Narrative Culture 10 (2): 171–88.

https://doi.org/10.1353/ncu.2023.a903843

Montanari, B. and S.I. Bergh. 2019. ‘Why women’s traditional knowledge matters in the production of natural product development: The case of the Green Morocco Plan’. Women’s Studies International Forum 77.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2019.102275

Myers, N., F. Middelhoff and A. Peselmann. 2023. ‘Stories are seeds. We need to learn how to sow other stories about plants’. Narrative Culture 10 (2): 266–76.

https://doi.org/10.1353/ncu.2023.a903848

‘Najstaršia lipa na Slovensku má 715 rokov: Matús Čák Trenčiansky ju zasadil zo škodoradosti!’ 2016. Nový Čas 21 February: https://www.cas.sk/clanok/365302/najstarsia-lipa-na-slovensku-ma-715-rokov-matus-cak-trenciansky-ju-zasadil-zo-skodoradosti/. (accessed 23 August 2023).

Nitzke, S. 2023. ‘Narrative trees: Arboreal storytelling and what it means for reading’. Narrative Culture 10 (2): 206–25.

https://doi.org/10.1353/ncu.2023.a903845

Norkunas, M. 2017. ‘Are trees spiritual? Do trees have souls? Narratives about human tree relationships’. Narrative Culture 4 (2): 169–84.

https://doi.org/10.13110/narrcult.4.2.0169

Novotná, M. and M. Kvietok. 2015. ‘Nové Hromadne Nálezy z Doby Bronzovej z Moštenice’. Slovenská Archeologia LXIII: 209–37.

Novotná, M. 1980. Die Nadeln in der Slowakei. Prähistorische Bronzefunde. Abteilung XIII. Band 6. Műnchen: C.H. Becksche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

Ožďani, O. 2015. ‘Poherbiská a pohrebný rítus’. In Staré Slovensko: Doba Bronzová. Vol. 4. Nitra: Archeologický ústav SAV. p. 161.

Palovic, Z. and G. Bereghazyova. 2020. The Legend of the Linden: A History of Slovakia. Bratislava: Hybrid Global Publishing.

Pember, M.A. 2019. ‘Native Americans Troubled By The Cultural Appropriation Of Smudging’. Beauty Independent (20 May, 2019) https://www.beautyindependent.com/

native-americans-troubled-appropriation-commoditization-smudging/. (accessed 11 Jan. 2024).

Personal communication. S. Ďuranová. Slovak Agricultural Museum, Nitra. October 2018.

Personal communication. Mária Hajnalová. November 2018.

Personal communication. Mária Izakovičová. August 2019.

Personal communication Dr Steggman-Rajtar (2019)

Personal communication, Alena Chovanec. August 2023.

Phillips, L.G. and T. Bunda. 2018. Research, Through, With and As Storying. Abingdon: Routledge.

https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315109190

Pluciennik, M. 2015. ‘Authoritative and ethical voices: From diktat to the demotic’. In Van Dyke and Bernbeck (eds), Subjects and Narratives in Archaeology. pp. 55–82.

https://doi.org/10.5876/9781607323815.c003

Ranco, D. and J. Haverkamp. 2022. ‘Storying indigenous (life)worlds: An introduction’. Genealogy 6 (25): 1–9.

https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy6020025

Repka, D. 2018. ‘Intentionally broken vessels in Celtic graves: Evidence of funerary rites in La Téne period’. Archeologické rozhledy LXX: 239–59.

https://doi.org/10.35686/AR.2018.9

Reyes-Garcia, V. 2010. ‘The relevance of traditional knowledge systems for ethnopharmacological research: theoretical and methodological contributions’. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 6: 32.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-6-32

Rival, L. 1998. ‘Tree, from symbols of life and regeneration to political artefacts’. In Rival (ed.) The Social Life of Trees: Anthropological Perspectives on Tree Symbolism. Oxford: Berg. pp. 1–36.

https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003136040-1

Robinson, D.G., C. Ammer, A. Polle, J. Bauhus, R. Aloni, P. Annighöfer, T. Basin, M. Blatt, A. Bolte, H. Bugmann, J. Cohen, P. Davies, A. Draguhn, H. Hartmann, H. Hasenauer, P. Hepler, U. Kohnle, F. Lang, M. Löf, C. Messier, S. Munné-Bosche, A. Murphy, K. Puettmann, I. Marchant, P. Raven, D. Sanders, D. Seidel, C. Schwechheimer, P. Spathelf, M. Steer, L. Talz, S. Wagner, N. Henriksson and T. Näsholm. 2023. ‘Mother trees, altruistic fungi, and the perils of plant personification’. Trends in Plant Science 29 (1): 20–31.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2023.08.010.

Russel, L. 2018. ‘Osage Nation dedicates tree outside Smallin Cave in Christian County’. KY3 29 March. https://www.ky3.com/content/news/Osage-Nation-dedicates-tree-outside-Smallin-Cave-in-Christian-County-478308283.html (accessed 30 August 2023).

Silverstein, S. 1964. The Giving Tree. New York: Harper & Row Publishing.

Sovičová, L. 2010. Jedovaté Rastliny V NPR Regetovské Rašelinisko. Diplomová práca. Slovenská Nitra, Slovak Republic: Poľnohospodárska Univerzita v Nitre.

Spector, J.D. 1993. What It Awl Means: Feminist Archaeology at a Wahpeton Dakota Village. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press.

Spichak, S. 2022. ‘Psychedelics are surging – at the expense of indigenous communities’. The Daily Beast (26 Dec. 2022): https://www.thedailybeast.com/psychedelics-are-surging-at-the-expense-of-indigenous-communities (accessed 12 January 2023).

Storl, W.-D. 2004. Magické Rostliny Keltů: Léčitelství Rostlinná Kouzla Stromový Kalendář. Volvox Globator.

‘Striga’. 2014. Centrum pre tradičnú ľudovú kultúru: https://www.ludovakultura.sk/polozka-encyklopedie/striga/ (accessed 3 April 2019).

‘Symbols’. 2023. Zuzana Čaputová, presidentka Slovenskej republiky. Kancelária prezidenta SR: https://www.prezident.sk/en/page/symbols-and-currency/ (accessed 24 August 2023).

Tenche-Constantinescu, A., C. Varan, Fl. Borlea, E. Madoşa and G. Szekely. 2015. ‘The symbolism of the linden tree’. Journal of Horticulture, Forestry, and Biotechnology 19 (2): 237–42.

‘The guardian of Great Moravia’s secrets’. ND. European Tree of the Year: https://www.treeoftheyear.org/previous-years/2019/Strazkyne-velkomoravskych-tajemstvi (accessed 10 August 2023).

‘The opium habit: The most abject of slavaries – is there any emancipator?’. 1887. Southern Standard (McMinnville, Tenn.) 19 November, p. 6: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86090474/1887-11-19/ed-1/seq-6/ (accessed 15 April 2023).

Tsymbalyuk, D. 2023. ‘I dream of seeing the steppe again: Plant stories in the context of Russia’s war on Ukraine’. Narrative Culture 10 (2): 246–65.

https://doi.org/10.1353/ncu.2023.a903847

Tuwaleststiwa, P. and J. Tuwaletstiwa. 2015. ‘Landscape: The reservoir of the unconscious’. In Van Dyke and Bernbeck (eds) Subjects and Narratives in Archaeology. pp. 101–22.

https://doi.org/10.5876/9781607323815.c005

Tyburski, W. 2013. ‘Hendryk Skolimowski on ecological culture’. Dialogue and Universalism 4: 75–86.

https://doi.org/10.5840/du201323450

Urbanová, K. 2018. ‘Prehistoric dressing for third millennium visitors. The reconstruction of clothing for an exhibition in the Liptov Museum in Ružomberok (Slovakia)’. EXARC Journal 3: https://exarc.net/issue-2018-3/at/prehistoric-dressing-third-millennium (accessed 3 March 2020).

US Geological Survey. 2023. Incorporating Indigenous Knowledges into Federal Research and Management. Webinar Series: https://www.usgs.gov/programs/climate-adaptation-science-centers/webinar-series-incorporating-indigenous-knowledges (accessed 3 June 2023).

Van Dyke, R.M. 2015. ‘The Chacoan past: Creative representations and sensory engagements’. In Van Dyke and Bernbeck (eds), Subjects and Narratives in Archaeology. pp. 83–100.

https://doi.org/10.5876/9781607323815.c004

Van Dyke, R.M. and R. Bernbeck (eds). 2015. Subjects and Narratives in Archaeology. Boulder: University of Colorado Press.

https://doi.org/10.5876/9781607323815

Van Dyke, R.M. and R. Bernbeck. 2015. ‘Introduction’. In Van Dyke and Bernbeck (eds), Subjects and Narratives in Archaeology. pp. 1–26.

https://doi.org/10.5876/9781607323815.c001

Whyte, K.P. 2013. ‘On the role of traditional ecological knowledge as a collaborative concept: a philosophical study’. Ecological Processes 2 (7): 1–12.

https://doi.org/10.1186/2192-1709-2-7

Wohlleben, P. 2015. The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate. Discoveries from a Secret World. Műnich: Ludwig Verlag.

Zipes, J. 2012. ‘Cultural evolution of storytelling and fairy tales: Human communication and memetics’. In The Irresistible Fairy Tale: The Cultural and Social History of a Genre. Princeton University Press: Princeton. pp. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.23943/princeton/9780691153384.003.0001

Zuzana Chovanec earned a Ph.D. in Anthropology from the State University of New York at Albany in 2013 and served as Fulbright Scholar to the Slovak Republic in 2018–2019. Her research has primarily focused on organic residue analysis on archaeological materials, the relationships ancient people maintained with the plant world, especially multi-purpose plants like the opium poppy, and the Bronze Age in Cyprus, but also deals with historic preservation matters in North America. She was born in Trnava, Slovakia and has lived in the USA from a young age.

Email: zuzana.chovanec@gmail.com

1 London, ‘Ethnographic and ethnoarchaeological insights’, pp. 99–100.

2 Maggio, ‘The anthropology of storytelling and the storytelling of anthropology’, pp. 90, 92.

3 Pluciennik, ‘Authoritative and ethical voices’, pp. 55, 61–62.

4 Aggarwal, ‘Traversing lines of control: Feminist anthropology today’, p. 17; London, ‘Ethnographic and ethnoarchaeological insights’, p. 120.

5 Pluciennik. ‘Authoritative and ethical voices’, p. 62.

6 Ibid, p. 55.

7 In Van Dyke and Bernbeck, ‘Introduction’, pp. 3–6.

8 Ranco and Haverkamp, ‘Storying indigenous (life)worlds’, p. 2.

9 Grötsch and Palmberger, ‘Introduction’, p. 4.

10 Ibid., p. 4.

11 Ibid., p. 5.

12 Ibid. pp. 5–6.

13 London, ‘Ethnographic and ethnoarchaeological insights’, p. 97.

14 Ibid.

15 Van Dyke and Bernbeck, ‘Introduction’.

16 Ibid., p. 19.

17 Tuwaleststiwa and Tuwaletstiwa. ‘Landscape’, p. 102.

18 Van Dyke, ‘The Chacoan past’, p. 93.

19 Phillips and Bunda, Research Through, With, and As Storying, p. 7.

20 Ibid., p. 8.

21 Ibid., p. 10.

22 The social, historical, and environmental implications of Indigenous storytelling – and the traditional knowledges that underpin them – are inseparable from the acknowledgment that there are other ways of knowing. But they are also inseparable from modern historical realities (see Whyte ‘On the role of traditional ecological knowledge’ for an introduction to these concepts and the USGS Incorporating Indigenous Knowledges webinar series for case studies). These contemporary conversations have specific aims for the Indigenous communities that strive to ensure their sovereignty and prosperity.

23 Dever, ‘Women in archaeology and antiquity’, pp. 183–84.

24 Montanari and Bergh, ‘Why women’s traditional knowledge matters’.

25 Kelly and Ardren, Gendered Labor in Specialized Economies.

26 Montanari and Bergh, ‘Why women’s traditional knowledge matters’, p. 4.

27 Reyes-Garcia, ‘The relevance of traditional knowledge systems’, p. 5.

28 Ibid., p. 6.

29 Phillips and Bunda, Research Through, With, and As Storying, pp. 12, 27.

30 Middelhoff and Peselman, ‘The stories plants tell’, pp. 171–88.

31 Myers, Middelhoff and Peselmann, ‘Stories are seeds’, p. 276.

32 Tyburski, ‘Hendryk Skolimowski on ecological culture’.

33 Myers, Middelhoff and Peselmann, ‘Stories are seeds’, p. 269.

34 Tyburski, ’Hendryk Skolimowski on ecological culture’, pp. 81, 85.

35 Spichak, ‘Psychedelics are surging’; Pember, ‘Native Americans troubled’.

36 Tsymbalyuk, ‘I dream of seeing the steppe again’, pp. 248–49.

37 Marder, ‘A philosophy of stories plants tell’, pp. 189, 196.

38 It should be noted that various mortuary practices are documented during Central European prehistory, with cremation predominating in certain periods. See Furmánek and Mitáš, ‘Poherbiská a pohrebný rítus’, pp. 268–71; Bátora, ‘Poherbiská a pohrebný rítus’, pp. 117–24; Furmánek, ‘Kov’, pp. 223–45; Furmánek, ‘Hromadné nálezy kovových predmetov’, pp. 288–89; Ožďani, ‘Poherbiská a pohrebný rítus’, p. 161.

39 See Novotná and Kvietok ‘Nové Hromadne Nálezy z Doby Bronzovej z Moštenice’ for details about a series of long metal pins with ends bent that were bound together and buried in four Bronze Age metal hoards on a hill overlooking Moštenica.

40 Chovanec and Flourentzos, ‘A review of opium poppy studies’, p. 146; Merlin, On the Trail of the Ancient Opium Poppy, p. 92.

41 Bernáth ‘Utilization of poppy seed’, p. 338. Merlin, On the Trail of the Ancient Opium Poppy, p. 91.

42 Chovanec and Flourenztos, ‘A review of opium poppy studies’, p. 146; Kapoor, Opium Poppy, p. 162; Merlin, On the Trail of the Ancient Opium Poppy, p. 91.

43 De Quincey, Confessions of an Opium Eater; Kapoor, Opium Poppy, p. xv; ‘The opium habit’, p. 6.

44 Chovanec and Flourtentzos, ‘A review of opium poppy studies’; Chovanec, ‘Examining the history of the opium poppy’; Hajnalová, Archeobotanika v dobej bronzovej na Slovensku.

45 Sovičová, Jedovaté Rastliny V NPR Regetovské Rašelinisko, p. 39.

46 Marec, Požehnaj tieto dary; Beranová, Jídlo a Pití. V Pravéku a ve Stredovéku‘, pp. 72–73, 255.

47 Abrahámova and Čechovičová, Maková knižka, p. 17; personal communication Dr Steggman-Rajtar (2019).

48 Fejér and Salamon, ‘Poppy (Papaver somniferum L.) as a special crop’; Hajnalová, Archeobotanika v dobej bronzovej na Slovensku, p. 85.

49 Chovanec and Flourtentzos, ‘A review of opium poppy studies’; Chovanec, ‘Oil, seeds, and cultural symbols’; Merlin, ‘On the trail of the opium poppy’.

50 Lančaričová, Havrlentova, Muchová and Bednárová, ‘Oil content and fatty acids composition of poppy seeds’.

51 Chovanec. ‘Cracking the history of the olive’, p. 46; Kapoor, Opium Poppy, p. 97.

52 Jurgová and Kaššová, Mak na našom stole, pp. 8–11.

53 Chovanec and Flourentzos, ‘A review of opium poppy studies’, pp. 145–47; personal communication, M. Hajnalová (2018).

54 Chovanec, ‘Examining the history of the opium poppy’.

55 Abrahámova and Čechovičová, Maková knižka, p. 17; Jurgová and Kaššová, Mak na našom stole, pp. 8–11; ‘Striga’, Centrum pre tradičnú ľudovú kultúru.

56 See Chovanec, ‘Examining the history of the opium poppy’ for a discussion of these.

57 Personal communication, Mária Izakovičová, Alena Chovanec, Aug. 2019; personal communication, S. Ďuranová. Slovak Agricultural Museum, Nitra, Oct. 2018.

58 Cooper, Traditional Slovak Folktales, pp. xxiv–xxvii.

59 Ibid., p. xxv.

60 Ibid., p. xxvii.

61 Ibid., p. 281.

62 Ibid., p. xxvii.

63 Francisci in Cooper, Traditional Slovak Folktales, p. 293.

64 Phillips and Bunda, Research Through, With and As Storying.

65 Zipes, ‘Cultural evolution of storytelling and fairy tales’, p. 2.

66 Franks in Ibid., p. 4.

67 See Urbanová, ‘Prehistoric dressing for third millennium visitors’ for reconstruction; and Novotná, Die Nadeln in der Slowakei. for full classification of pins.

68 Novotná and Kvietok, ‘Nové Hromadné Nálezy z Dobe Bronzovej z Moštenice’.

69 Ďuríčková and Pavlovičová-Baková (eds), ‘Čižiček, čižiček, vtáčik maličký’, p. 158. Personal communication, Alena Chovanec, 2019, 2023.

70 Brück, ‘Hoards, fragmentation and exchange’; Marcus, ‘Dressed to kill’; Repka, ‘Intentionally broken vessels’, p. 239.

71 Rival, ‘Tree, from symbols of life and regeneration to political artefacts’.

72 Wohlleben, The Hidden Life of Trees.

73 Robinson et al., ‘Mother trees, altruistic fungi, and the perils of plant personification’.

74 Nitzke, ‘Narrative trees’, pp. 208–09.

75 Bellan, ‘Stromy našich životov’, p. 8; ‘Najstaršia lipa na Slovensku má 715 rokov’.

76 ‘The guardian of Great Moravia’s secrets’.

77 Bellan, ‘Stromy našich životov’; ‘Symbols’. Zuzana Čaputová, presidentka Slovenskej republiky.

78 The British Museum, ‘Biatec’; Palovic and Bereghazyova, The Legend of the Linden, p. 30.

79 Storl, Magické Rostliny Keltů: Léčitelství Rostlinná Kouzla Stromový Kalendář pp. 258–60; Personal communication, A. Chovanec.

80 Russel, ‘Osage Nation dedicates tree’.

81 Frazer, The Golden Bough.

82 Hutton, ‘Sir James Frazer’.

83 Frazer, The Golden Bough, p. 106a.

84 Hutton, ‘Sir James Frazer’.

85 Frazer, The Golden Bough, pp. 113–14b.

86 Ibid., pp. 114–a-b; Tenche-Constantinescu et al. ‘The symbolism of the linden tree’, p. 239.

87 Ibid., p. 123a.

88 Ibid., pp. 259–60a.

89 Silverstein, The Giving Tree.

90 Norkunas, ‘Are trees spiritual’, p. 170.

91 Frazer, The Golden Bough, p. 109a.

92 Middelhoff and Peselmann, ‘The stories plants tell’.

93 Maggio, ‘The anthropology of storytelling and the storytelling of anthropology’, p. 91.

94 Ibid., p. 97.

95 Patterson in Zipes, ‘Cultural evolution of storytelling and fairy tales’, p. 13.

96 Frank, Letting Stories Breathe.