Isabella Clarke

Conversations with Trees: The Experiences of an Arboreal Pilgrim

ABSTRACT

This is a tale of my connection with trees, a connection from which conversations arose. My aim is to chart my journey from tree-lover to tree-listener and to share the wisdom of the trees. I do not offer any explanation for these experiences, though I will express my sometimes confused and uncertain responses, my questions and concerns, my attempts, as a person who sits more on the side of science than spirit, to make sense of what happened. Ultimately, as I hope these conversations will demonstrate, I decided that what I gained from the trees was more significant than the how or the why of it.

lways, I have loved trees. As a child, a wanderer, I tried to lose myself in the wooded areas around our rural home in England’s south-western peninsula. Under the canopy of oak and ash, the understory of hazel and hawthorn, I had the magical feeling of swimming through green light. And I felt, strangely, both thrilled and safe. That is a feeling I rediscovered 30 or so years later while volunteering for a conservation organisation. The mysteriously enlivening peace of woods.

lways, I have loved trees. As a child, a wanderer, I tried to lose myself in the wooded areas around our rural home in England’s south-western peninsula. Under the canopy of oak and ash, the understory of hazel and hawthorn, I had the magical feeling of swimming through green light. And I felt, strangely, both thrilled and safe. That is a feeling I rediscovered 30 or so years later while volunteering for a conservation organisation. The mysteriously enlivening peace of woods.

The longer I spent with trees, the more profound the feeling-state, and I wanted to understand it. So I researched, and this eventually led me to seek out the counsel of a Druid, Harriet Sams. She invited me to go to a tree and, when outside the reach of its canopy, to ask the tree if I could enter. She said, ‘Notice how you feel outside the canopy, at the very liminal point and when under the canopy.’ Next, I was to ask the tree if she were willing to teach or guide me, and, if the response were positive, to express my questions or concerns and simply wait to see what arose. That opened the door, and I eagerly crossed the threshold. Messages were slow in coming and, at first, I wasn’t sure if I was confabulating. I stuck with it, curious and excited. Subsequently, I have done this many times. On some occasions, there has been no response. On others, I have felt comforted, supported and guided. On many, I have indeed conversed with trees.

Of course, I am not a trained Druid, nor do I claim to be any kind of shaman, or to have paranormal abilities. Instead, please accept these conversations in the spirit in which I offer them: as truthful representations of the experiences I have had sitting with trees.

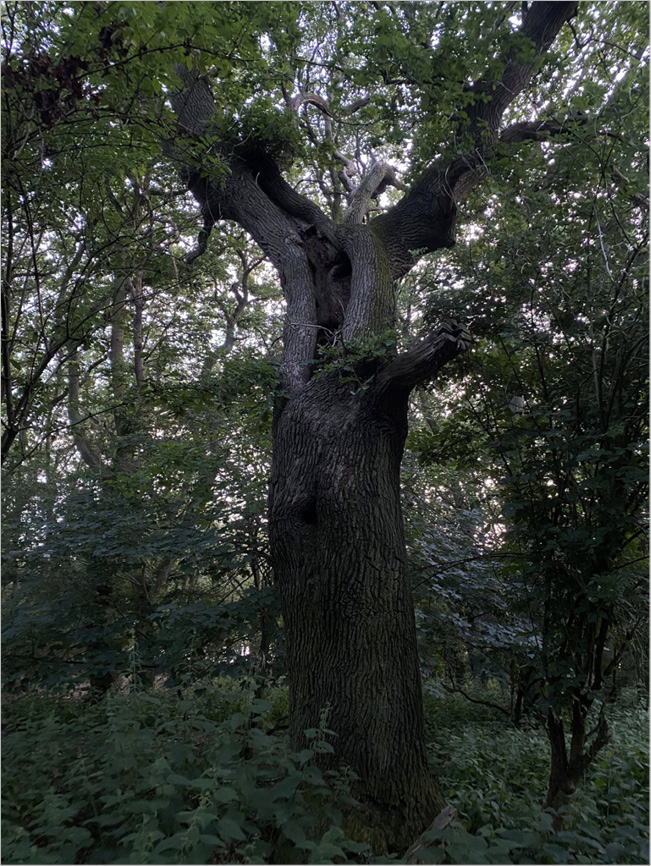

The accompanying photographs, not of exceptionally high quality as they were taken with a smartphone, re-assert the individuality of the trees. Each one is a being embedded in landscape and community; embodied in his or her own distinctive way. They were taken for the same reason that others photograph their friends: as mementos of times shared with loved ones.

Copse Oak – c.250-year-old Quercus robur

Figure 1.

Copse Oak.

Source: Author.

This tree has been of great support to me during difficult times. There is a comfortable fork between two roots, where I sit and lean back against the trunk, as though embraced by the tree. After speaking to Harriet, and asking the Copse Oak’s permission, I sought his counsel, telling him that I have all these ideas and sparkling thoughts and while they feel connected, it is as if they are entangled, rather than in some kind of logical chain, and they go nowhere. Like a whole forest of mycelium without any trees.

He seemed to think this was fine. Then he said, ‘Oh… You don’t have as much time as we have.’

I agreed and said I needed to know what to do sooner than a tree would.

The Copse Oak said, ‘You must find the trees [by which I understood he meant any beings] and give them what they need, which is not necessarily what they want.’

I asked, ‘Don’t trees know what they what?’

The Copse Oak replied, ‘Where there is absence, how can anyone know what should be there?’

When I asked what I needed to give, what was needed, all I got was ‘heart’.

That seemed as far as I would progress on that line of inquiry.

I sat in silence.

A bee flew in and out of a tiny space between my foot and one of the oak’s roots. She was feeding her brood. Blue tits called warnings and blackbirds sang. A loud crow flew over. A buzzard circled, looking down. An old field maple creaked; the fallen bough of an ash, still attached to the stem, groaned. Insects buzzed and whizzed. Swifts screamed high, high above.

I told the Copse Oak (CO) that I wanted to feel a sense of true belonging.

CO: You do belong here. I’d be happy for your bones to fall at my base and return to the earth.

Me: I’d like to belong while I am alive.

CO: Don’t you feel as if you belong?

Me: Yes… but the poplars are dying [in this particular wood] and the world’s all wrong!

CO: First, all things die. Second, you cannot belong in a world that does not exist. Only in the world that does. You belong AND everything is wrong.

Me: Staying with the trouble?1

CO: If you like. By the way, have you ever seen a tree afraid?

Me: No… I didn’t know trees were afraid. What of? Chainsaws? Death? Pests?

CO: We are only afraid of being unrooted [sic]. We fear for our roots.

This conversation, through originating in my personal neurotic sense of always being an outsider, helped me through enhancing my understanding of very different beings, trees. Place matters. Connection to place is paramount. No tree grows in an ideal position: each tree contends with shade, distributed nutrients and minerals, periods of drought or waterlogging, pest infestation, lightning strikes. Yet the tree exists, seeks to flourish, in the world that he finds himself in. That world, the agency of the world, informs the tree’s becoming. The form of the tree is a record of the life lived in that place at that time. Relationships and compromises, solutions to societal problems turned into oak. Further, the tree himself, while moulded by the agency of the world also, it seemed, plays an agential role in creating the environment in which he co-becomes. This hypothesis seemed to be supported by some of the comments of the oldest tree I regularly visit.

King Oak – c.700-year-old Quercus robur

Figure 2.

King Oak, detail of the trunk.

Source: Author.

When King Oak (KO) spoke, he did so slowly. The conversation was dreamlike. I asked him how he had survived so long, outside a wood and so, maybe, without a vast supportive interconnected mycelial system.

KO: I am so old that I support my own support system.

Me: We humans don’t do that!

KO: Maybe you are not old enough. You should worship trees.

Me: I think the Druids did.

KO: Well, they were old.

Me: But they were in the past!

KO: Humans were born again when they began to make things that they should not make; and they have not grown out of their infancy.

Me: What shouldn’t we have made?

KO: Things that trees don’t want to be.

Me: What do trees want to be?

KO: Safe houses. We like to be safe houses. Not barriers, not weapons, not transport.

This conversation had taken some time. Although I felt safe and welcome, I also felt nauseous, drugged, as though I couldn’t remain any longer without passing out or being physically sick. Considering this now, I still cannot explain the physical sensations, the hallucinatory vibe. However, I have felt a similar disquiet with ancient pollards.

There is something decidedly other about them. Pollarding, a pruning system involving the removal of the upper branches, can extend the life of a tree, with the process giving a boost of vitality. Like coppicing or cutting back roses. I get that. But there is an odd aura about these trees; a kind of concentration and a ‘holding’, as though their energy is constrained. So, while there is a deep acceptance about the shape they now are, there seems also to be an intense focus on compensating for the losses suffered. Each branch is an investment as well as a source of energy. Their removal must be, initially, traumatic. And yet it seems as though the arboreal response is always one of post-traumatic growth. The level of resilience is stunning.

Figure 3.

Pollard at Burnham Beeches.

Source: Author.

In Ancient Woodlands, like Burnham Beeches2 in Buckinghamshire to the west of London, you see many pollarded oaks and beeches. The real veterans hollow out, letting the inner wood rot and provide sustenance for invertebrates, while the living outer wood acts as an ever more stable structure. Sitting with these trees, I experienced a profound insight – and one that we humans seem to struggle with: the blessing of being hollow. The words start to merge. The trees are hollow; they are hallowed; they are holy. Yet, although I was granted this wisdom when I sat with the pollards and wrote the messages down as they were given to me, I forgot, as you will see. Indeed, trees often repeat, in new ways, the same teachings. Their patience seems to be limitless.

In the Beeches, I met one oak tree who touched me deeply. The Stag’s Head Oak – the upper branches are dead and rise into the sky like the antlers of a stag – showed me the incredible creativity and artistry of dying and ageing – how counterintuitive! The architecture of the tree, hollowing in places, dropping some branches, having others as bare steeples of grandeur, richly leafed elsewhere… he was an autopoetic masterpiece. The incredible vitality that enables the tree to keep creating during the corrosive period of decline. I sensed the majesty of his swirls and folds. The strength of the embrace and the hold. And the absence within that allows the forms of inner wood and internal structures to be seen. It is his breaking open that releases his essence.

Figure 4.

Detail of Stag’s Head Oak.

Source: Author.

‘It’s all about what you do with your dying,’ he said to me.

When I left this tree, I could not turn my back on him and walk away. I found myself stepping backward, like a courtier departing from a monarch, and then falling to the ground, denimed knees hitting soft earth and my head bowing. The tremendous power. Allow yourself to feel such power and the energy of it is destabilising. On my knees before an ancient tree and speechless. Or almost speechless. ‘Thank you,’ I was saying. And, ‘I’m sorry!’ How can a human not be sorry? The force of it left me stunned.

The conversation with another tree focused more on what we do with our living.

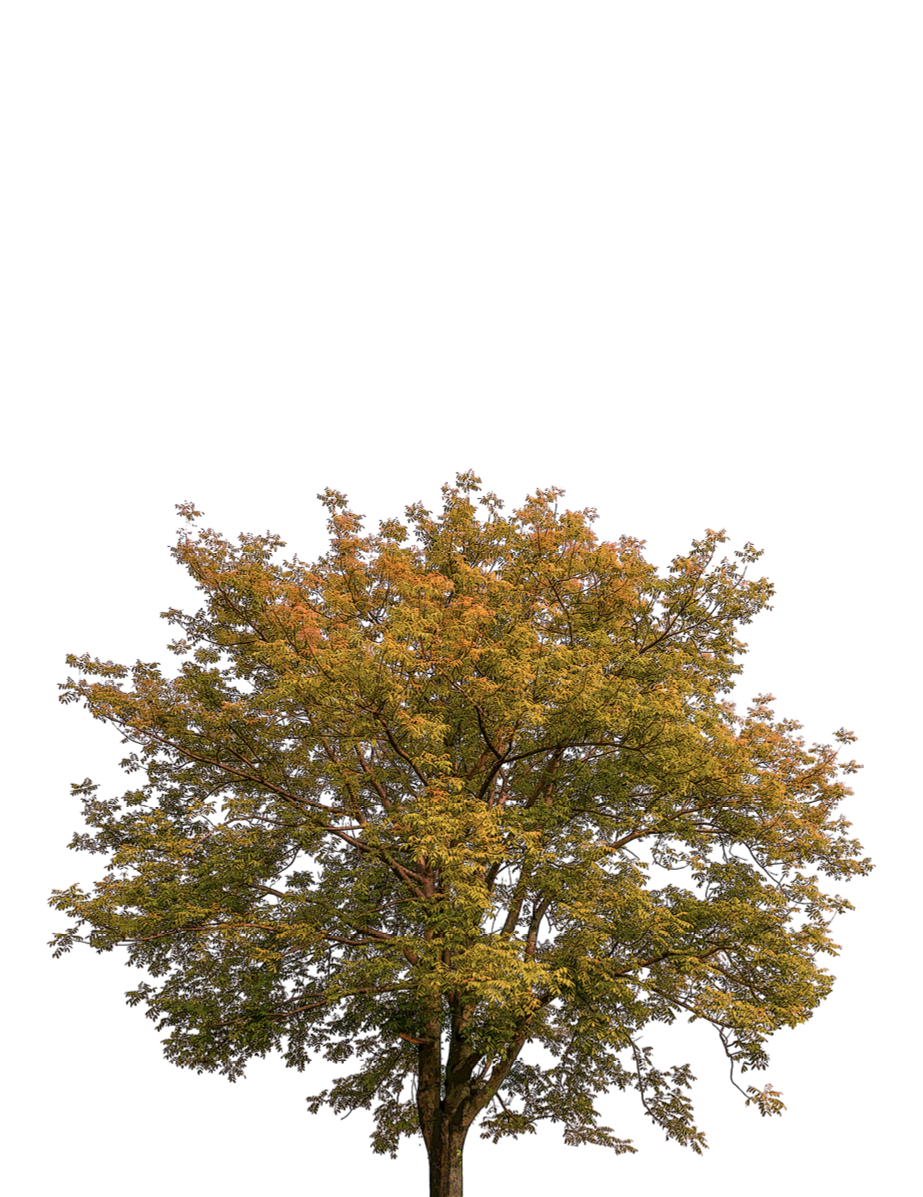

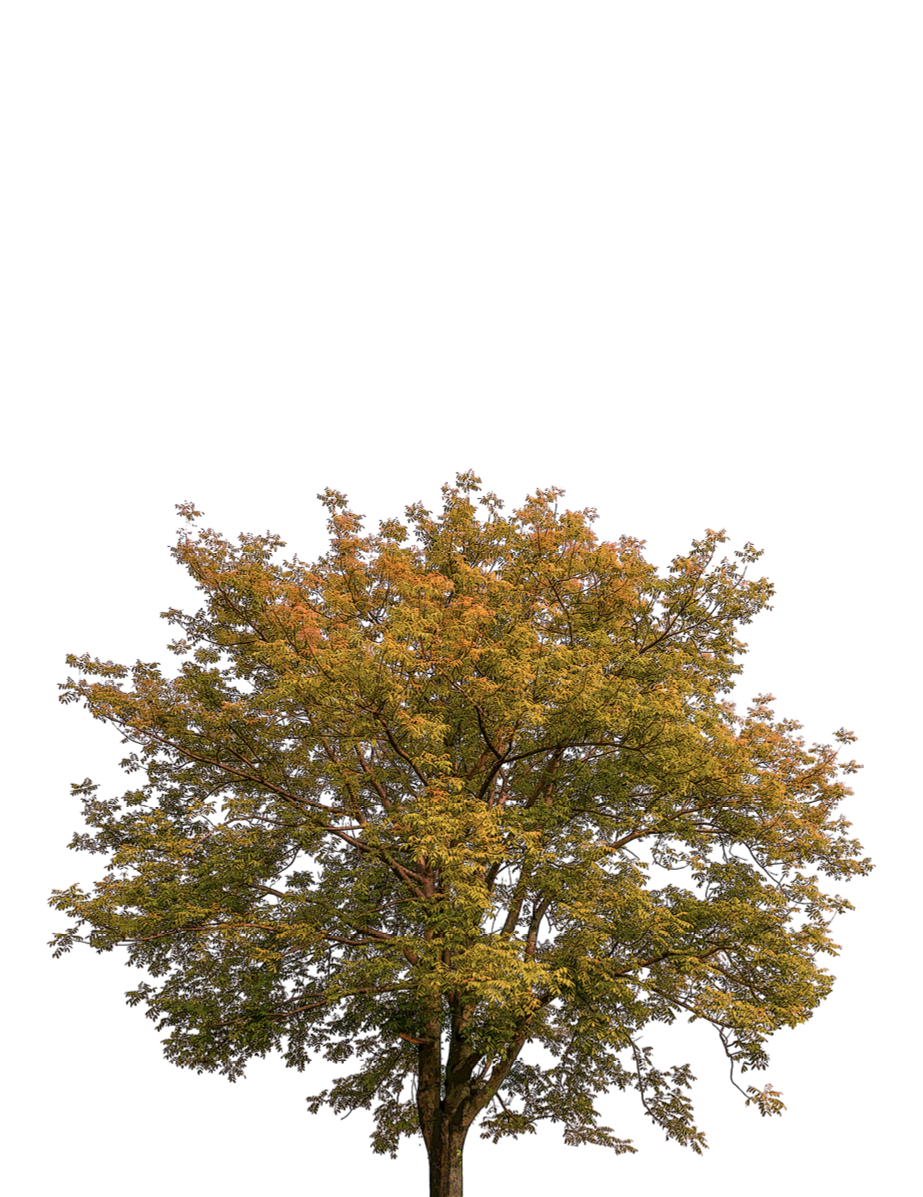

Mother Oak – c.250-year-old Quercus robur

Figure 5.

Mother Oak.

Source: Author.

Mother Oak is another hedgerow tree, on the boundary between two golf courses. I asked her how she had survived through the centuries, as most of the surrounding trees were less than half her age. She said, ‘By inhabiting the borderline.’

I understood that she wasn’t simply referring to the boundaries between our human-created parcels of land. Instead, she was pointing to a deeper truth: that trees live between realms. Between air and earth, making life from fire and water. Trees are elemental alchemy. Deeper still, her message pointed to the creativity of existing in the in-between places. Between birth and death; heaven and earth; the material and the spiritual; the sacred and the profane. The place where dichotomies dissolve into non-duality.

She seemed open to further questioning, so I asked how we humans should live. No hesitation: ‘Take only what you need.’

‘But,’ I said, ‘There are so many of us… what happens, how do you cope if there are too many trees?’

She said, ‘There cannot be too many trees as trees cannot grow where there is not space and light.’

A sense of discomfort arose in me. That response seemed cold, uncaring. I was defensive, despite my concerns about human population. So, I asked her, rudely, abruptly, if she was at all compassionate.

The force of her reply was like my cells being invaded by the essence of tree. I felt as if I had been in the centre of a split-micro-second tornado and then enveloped into safety, into complete loving-kindness. I felt profoundly accepted. By a tree.

Shuddering, I was silent for a while. Hearing birds and foraging bees. Iron striking rubber. Golfers talking as balls led them from a mown lawn to a shaved lawn.

The moving, restless animal world. The abstract, hard-to-compute human-animal world.

I asked, ‘What is knowledge?’

And she said, ‘My knowledge is wood. I am my knowledge. I know what has been and what has been becomes me. There is no knowledge without happening. No knowledge without place.’

That made sense to me – and now that I bring these conversations together, I see that this is a consistent message. One the trees had to tell me again and again. Consider the Copse Oak’s comment about the tree’s fear of being ‘unrooted’ and the King Oak’s claim that he supports his own support system.

When I got up to leave the Mother Oak, I put my hand to her bark, wanting to say something, something right, but the tree cut in, telling me that there was nothing I could tell her of my heart, for when we connected, in that zinging moment of mutual acknowledgement, the connection was made… like fungal fibres… complete and lasting.

And I thought of my mother, who died in 1995, and felt the connection. Of my brother and sister-in-law in Devon, of my sister and my father, my close friends, and I felt the connection. I thought of the tame robin in my garden, of my dead and living companion-animals, of the fields and woods I frequent in this crowded island, of momentary passing special acquaintances (human, non-human and some of them places) and I felt the connection. Alive.

This is what really matters: the living connections between all earth entities. I sensed, in that moment with the Mother Oak, that my personal path toward wisdom involved re-establishing or reinvesting-with-mattering my entanglement with all else that is: the human, the animal, the plant and the place. This place, this earth-place, home. A planet made liveable by plants. A life made sustainable by trees.

And yet… I lose faith. I question. I misunderstand. And I forget.

I tried to work this through with a tree I call the Wayfarer Oak (WO).

Wayfarer Oak – c.200-year-old Quercus robur

Figure 6.

Wayfarer Oak.

Source: Author.

Me: Why am I finding this quest for wisdom so hard?

WO: There are different types of wisdom. The wisdom to understand, the wisdom to decide and the wisdom to connect. That is the one you seek. The one that’s related to connection.

Me: Oh… that makes sense and that is so helpful… but what is the wisdom of connecting?

WO: Being in touch, in conversation. Seeing how the communion enables two beings to come into existence through their mutual attention and entanglement. Creating each other as subjects through the acknowledgement of intra-action, through the recognition of connection. But the wisdom that arises from it is mind-altering: you accept that you become in the gaze of, conversation with, touch against, entanglement with the other. You accept that they are as much themselves as you are yourself.

Me: OK… I know I am willing to connect with much… but I am intolerant when it comes to humans, not all the time or even most of the time, but far too often. I judge and resent.

WO: That’s what bark is for.

Me: What?

WO: Trees are beings of many relationships and millions of connections. But we still need protection. To close off. You need more bark. But not too much. Too much bark and you start to jettison the living wood – which is something many humans do in their enforced separation from the world or from ideas they don’t like. There is wisdom in determining how much bark is right. Maybe it’s not unwise to separate from some other people.

Me: But I feel that I should be able to tolerate divergent viewpoints! I should not judge. I should be kinder!

WO: Why? You are not a god! You aren’t expected to be able to withstand everything. You are expected to be vulnerable. But not too vulnerable. Bark is the answer to keeping out what you need to keep out. It’s just that you can’t expect bark to protect you from everything. Only the things you truly need to protect yourself against.

Again, you see similar themes arising: the recognition of entanglement and situatedness. At the same time, the Wayfarer Oak’s forceful reminder that I am not some divine being who can be expected to cope with everything was new – and it made me laugh out loud. That is a lesson I try to call to mind when I feel grief over harms to and dismissal of the more-than-human. For I do struggle with others of my species. I feel frustration and anger. And yet, I am, of course, a human. As I walk through the fields and woods, the Flying People and the Four-Leggeds flee or hide. It is as devastating to see my kind do harm as it is to feel the results of that harm in the terrified responses of fellow earth beings.

Another tree helped me to experience a different reality – albeit just for few short minutes.

Water Willow – c.80-year-old Salix fragilis

Figure 7.

Water Willow.

Source: Author.

The Water Willow leans over so dramatically that I could walk up the main stem and position myself quite high up on an almost horizontal surface. I sat still and silent. A squirrel ran up the trunk to within a few feet of me, then turned onto another branch and scampered up and away. Some time later, a flock of tits flew into the branches above and around me. So close that I could hear their wingbeats. They made contact calls to each other. One gave an alarm call, and they all took off, but I didn’t move, and they returned to forage in the tree. I was inside a bell jar of birds.

‘This,’ said the Water Willow (WW), ‘is what it is like not to be human.’

I asked about the more-than-human: is it edenic or nature red in tooth and claw?

WW: Neither. Dying is the other side of the same thing that is living; suffering is the other side of pleasure. These things cannot be unbound because they are not separate. They are one thing. Because you are born you die. Because you have pleasure you can also have pain. There are no morals here. No justice. No rules or balancing out. No accounting of what makes a life worth living. It is the is. Humans are the only creatures who rail against what is. Yes, all beings struggle to live and to avoid suffering. And anything any one of them does limits the options for another being, or harms that other being, or kills that other being. There is no living without dying, no living without suffering. It is the is.

I experienced a radical discomfort. It is Unheimlich to sit with the irreconcilably other. Unheimlich literally means ‘not homey’ – a feeling radically opposed to the sense I often had that for trees ‘being-a-place’ is so critical – and is translated as ‘uncanny’. The uncanny had come up in a conversation with another oak tree.

Goddess Oak – c.250-year-old Quercus robur

Figure 8.

Goddess Oak.

Source: Author.

I named this oak on the bank of a pathway through a wooded area the Goddess Oak, as the hollowed-out area high in her trunk reveals shapes that form the face of a woman.

She had said, ‘I want you to know about the uncanny. Things can seem unkind or unfriendly – but that is not the condition of the messenger: it is instead part of the message. The purpose of this is to stop you romanticising and sentimentalising the natural world. You need to learn how to tell uncomfortable stories.’

I went back to her and sat again. I began by asking her about the nature of mystery.

GO: It is as it is. Transcendence lies in immanence.

Me.: It feels important to me. I am trying, always, to reach that transcendence. If, as you say, it is in immanence, then, well, how do I understand it?

GO: It just is. This is it.

Me: But…

GO: What more do you want than what is?

Me: I feel incomplete. Empty. Hollow.

[Note here that I had forgotten the wisdom of the pollarded trees at Burnham Beeches, who showed me the blessing of being hollow.]

GO: A hollow tree is strong.

Me: But I feel weak! I feel that I need to find this… this answer!

GO: What would you do if you were not in pain and afraid?

Me: Maybe I would do nothing.

GO: To do nothing is to be nothing.

Me: Are you saying that feeling hollow is… good?

GO: I am asking what you would do if you did not feel hollow.

Me: It can’t be good to feel hollow! There must be something that would complete me!

GO: …

Me: [Frustrated] Can’t you please share your wisdom with me?

GO: I always have and already do.

Me: What do you mean?

GO: Everything is everywhere at the same time.

Me: I don’t understand.

GO: Look here. Right here, right now. You see a man-made reservoir and a man-made landscape. I experience the aurochs and lynx; the old wildwood; the generations of your kind hunting and then farming; the deaths of the trees to come and the rebirths of the world after that. It is always already here.

Me: Like… block time?

GO: If that is what you call it. I call it consolation.

Ah, and how I am in need of consolation.

There is one tree above all trees who is special to me.

In the front field of the Devon farm where I grew up, an old oak tree used to grow over a well. The farm dates back five or six centuries, and the tree was probably older. At the time, I didn’t think about the oak much. I regarded ‘it’ as a landmark in the field. But in early 2023, I was being led in a guided meditation. We were to imagine looking at the moon and floating up to her. In my vision, I was lying under this old oak and seeing the moon through the leaves above me. When the meditation teacher suggested we let ourselves rise to the full moon, I felt a resistance. I experienced, somatically, the roots of the tree stretching around me, embracing me, holding me to the earth. The tree’s voice said, ‘Stay, child. This is where you belong.’

Although the farm has been sold along with most of the land, my father still owns the field where the oak tree stood. My brother lives in a cottage opposite our old house. When I visited him and my sister-in-law after this meditation experience, I went out to the tree for the first time in 30 years.

Grove Oak – c.350-year-old Quercus robur

Figure 9.

Under the canopy of the Grove Oak.

Source: Author.

The field is gradually turning to forest. The oak children of this great tree are spreading across the land. They have already filled the space between the far hedge and the tree. But I could walk under her vast canopy and sit in the saddle between the two stems, looking down at the well.

Ahead of me, under the canopy, was open space. And then, perfectly tracing the great tree’s branches, which spread to the ground around her, was a ring of young oaks. I was in what will be a grove. When the old tree died, there would be a circle of oaks around an open space. This, I thought, must be how a Sacred Grove forms. The dancing graces around the goddess tree and, at her passing, the graces remain. I felt a deep sense of belonging. In my heart was the knowledge that I would live here again. Yet the knowledge was not book-knowledge or reason-knowledge: it arose from mystery. And, paradoxically, from simplicity. The simplicity of life, of belonging, of living and dying, of the regeneration always present in the process of ageing. And I came to understand that transcendence resides in immanence and cannot be separated out. Meaning lies in being, the eternal becoming of being. That is all. The Sacred Grove was not here and yet it was here. And I thought of a line in the book I was listening to, a reworking of the Arthurian legends: ‘What of the King Stag when the young stag is grown?’3

In a state of dreamlike conviction I set up my wildlife camera just outside the canopy.

The following morning, I saw it had fired only three times. I was disappointed. So disappointed that I didn’t even look at the films. My brother said, ‘What were you expecting?’ ‘The King Stag,’ I said. He laughed.

When I got back to my present home, I downloaded the films. The first was the wind in the leaves. The third was me collecting the camera. The second was a roe deer stag, walking straight up to the camera.

Six months later, I returned to Devon. Before I set out, my sister-in-law told me that the oak had fallen the previous November. I felt broken. And when I went to the tree, the sight of cracked limbs, of the divided trunk halved at the saddle where I had sat like a heart torn apart, of the twinned crowns brought low devastated me. The Grove Oak had been sundered in two by years of stronger-than-normal winter winds and the roots, weakened in waterlogged soil, had ruptured. The pair of trunks and the arch of the crown now marked the perimeter of the Sacred Grove, with the reaching branchlets extending around the southernmost semi-circle of young trees. I tried to draw upon facts. That fallen trees like this make great habitat. That there are more living cells in a dead oak than a live one. I watched and listened to a robin singing his sweet and melancholy song from the tumble of wood.

And then I sought to reach my mind into the tree. I was asking for, demanding something. Assurance that the promise that I will, one day, come home was not broken by the Grove Oak’s breaking. Assurance that my summertime experience of transcendence in immanence when sitting with this tree was not just wishful thinking. Assurance that this is not some form of brutal proof that I have, over the last year, been confabulating. For how can there be mystery alive at the heart of the world if its messengers are toppled in their prime? If they are so brutally ‘unrooted’? I lived the words of the Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins in ‘I wake and feel the fell of dark, not day’, a poem about his struggles with his faith:

And my lament

Is cries countless, cries like dead letters sent

To dearest him that lives alas! away.

I am gall, I am heartburn. God›s most deep decree

Bitter would have me taste: my taste was me…4

The answer came to me like the final lines of George Herbert’s poem ‘The Collar’, in which faith is regained:

But as I raved and grew more fierce and wild

At every word,

Methought I heard one calling, Child!

And I replied My Lord.5

In the fallen tree, I had believed I was witnessing the reflection of my shattered hope, hope that had begun to bloom between the spreading roots and boughs of trees. Yet that is to misunderstand. I remembered then, in the intensity of the moment, something that the Goddess Oak had said, ‘I am not here to be your mirror. Maybe you are here to be mine.’ The trees were not showing me who I was, they were offering a suggestion for how I could be. That realisation opened my being to the presence of the Other. I felt, rather than heard, as I battled with my heart in the face of this oaken memento mori, composure and acceptance from the fallen oak. This is the deepest wisdom: the capacity to be at peace in a broken state. To live well in a world of suffering. To embrace tranquillity in the Anthropocene. To accept that everything is everywhere, all at once. The Grove Oak as acorn, sapling, mature tree, fallen giant. The Sacred Grove of the future and the wildwood of the past. Living is all about what you do with your dying. This moment captured so much that the trees had been telling me over the past year. And it captured too the sense of mystery, of all that lies unknown and unknowable.

I cannot claim to live the trees’ wisdom. For I am not at peace in this world of habitat destruction, biodiversity loss and climate chaos. I find it Unheimlich. However, what I have learned, and continue to learn, and what I experience when I sit, attuned and attentive, by one of the Standing People does provide consolation.

Issy Clarke is an independent researcher, broadcast journalist and conservation volunteer based in the UK. She writes on non-human animal cultures and relationships with the more-than-human, particularly free-living Animals and Plants. She enjoys sitting with Trees (and other non-human beings), and being receptive to their wisdom. Her work embraces the factual and scientific, the theoretical and ethical, and the speculative and imaginal.

Issy Clarke is an independent researcher, broadcast journalist and conservation volunteer based in the UK. She writes on non-human animal cultures and relationships with the more-than-human, particularly free-living Animals and Plants. She enjoys sitting with Trees (and other non-human beings), and being receptive to their wisdom. Her work embraces the factual and scientific, the theoretical and ethical, and the speculative and imaginal.

Email: issymclarke@gmail.com

1 I had recently been reading Donna Haraway’s Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016).

2 https://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/green-spaces/burnham-beeches-and-stoke-common/visit-burnham-beeches (accessed 1 May 2024).

3 Marion Zimmer Bradley, The Mists of Avalon (New York: Ballantine Publishing Group, 2000).

4 www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44396/i-wake-and-feel-the-fell-of-dark-not-day (accessed 1 May 2024).

5 www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44360/the-collar (accessed 1 May 2024).