Alissa Ujie Diamond

Entangled Genealogies: Mulberries, Production

of Racial Categories,

and Land Development

in Central Virginia

ABSTRACT

This article traces the history of white mulberry (Morus alba) alongside the histories of Charlottesville, Virginia and the author’s genealogy as a mixed-European and Asian-descended American, to explore the situated and connected histories between plants, land and humans. This approach allows the re-mixing of various kinds of knowledge (designerly, personal, archival, scholarly) available to the author, and explores the ways in which attention to place, plant and people can reveal the entanglements between living actors and mega-systems of racial capitalism, and point toward further avenues for inquiry for those seeking to build worlds beyond capitalism

KEYWORDS

Morus alba, Charlottesville, racism, capitalism, landscape history, migration

ntroduction

ntroduction

Origin: China

Background: White mulberry was introduced to the U.S. during colonial times for the purpose of establishing a silkworm industry.

Distribution and Habitat: White mulberry is widespread in the U.S., occurring in every state of the lower 48 except for Nevada. It invades old fields, urban lots, roadsides, forest edges, and other disturbed areas.

Ecological Threat: White Mulberry invades forest edges and disturbed forests and open areas, displacing native species. It is slowly outcompeting and replacing native red mulberry (Morus rubra) through hybridization and possibly through transmission of a harmful root disease …

Prevention and Control: White mulberry seedlings can be pulled by hand. Otherwise, cut the tree and grind stump or paint the cut surface with a systemic herbicide like glyphosate or girdle the tree (see Control Options)

[White mulberry (Morus alba), plant fact sheet excerpt from Plant Invaders of Mid-Atlantic Natural Areas]1

This fact sheet describes Morus alba or white mulberry, a scrubby mid-size tree that I saw every day in hedgerows, fence lines and other marginal spaces in Charlottesville and Albemarle County, Virginia, where I lived and worked for seventeen years. The directives on the sheet reflect the generally accepted management ethic with regard to ‘invasive’ plants like the white mulberry: eliminate them to ‘preserve’ biodiversity. I am a landscape architect, so I have specified pesticides to eliminate nuisance trees on clients’ properties in the region. But this description also zings me every time, calling back to experiences on schoolyards where features of Asian-ness exhibited in physical body and family’s foods and language brought out the same metaphors of pollution, invasion and the necessity of elimination.

This description’s wording reveals three aspects of the set of relations it proposes. First, it assumes the ideal future is a pure place, a landscape that has undergone a process of ‘restoration’ that paradoxically returns to a state of ideal native biodiversity. Second, it assumes it is speaking to a controlling subject who ‘manages’ or ‘maintains’ the land to this desired state. Third, it evokes the language of racism and xenophobia, to lend urgency to the threat of invasion. It implies but also hides this triad of presumptions about person, plant and place.

Methods and thesis: Plants, person and place

This article traces human relationships to place through the mulberry. This story uncovers formations that thread through successive historical natures2 involving people, plants and place. I find broader repeating patterns that emerge from and cut through the changing material strategies, ecological arrangements and social formations human actors try to use to derive profit from land and people. The three formations that come into focus are the environmental ‘enemy’; evolving social and ecological practices that extract profit from land and people; and a kaleidoscope of shifting spatial-racial categories of ‘white’ and ’Asian‘ in relation to parallel formations of ‘Black’ and ‘Indigenous’ as labels and attitudes that move between human and extra-human beings. It traces continuities in various modes of capitalist land-use over time, and explores the ways systems recycle, reorient and reassign logics of racial hierarchy in changing contexts.

I use the particular examples of person (my genealogical history, particularly my Ujie and Durie antecedents), place (Charlottesville, Virginia where I lived for seventeen years) and plant (history of Morus alba) because tracing these three threads together allows me to remix the different types of knowledge available to me as a researcher.3 Studying Morus alba allows me to draw in my knowledge as a registered landscape architect, a person given societal authority to provide official recommendations on ‘proper’ management of landscapes. My position as a mixed-heritage Euro-Asian American gives me familial and genealogical access to stories about how I came to be here in terms of broader historical and economic forces and migrations, stories about variegated racialisations my antecedents faced or embraced, and personal experiences of living in a racialised and gendered body in the United States and Japan. Many histories focus on the historical lives of regional ecosystems and cultivated plant complexes,4 on physical and cultural histories of bounded places5 and on the evolution of categorisations of people.6 Tracing my historically situated relationships to the white mulberry effectively ‘rebundles’ available knowledges and brings patterns I could not trace otherwise to light, and allows me to explore the ways racialisations of human and extra-human creatures move back and forth to create human-natural cultural complexes.7

Seventeenth century: Mulberries, silk and intra-European racialisms and migration

In the historical record, white mulberries are conjoined with silk-making, as the silkworm (Bombyx mori) prefers the leaves of Morus alba over other food sources. Early material remains of sericulture appear in China,8 and humans brought silk technology and white mulberry trees to Japan, through the Mediterranean and into France by the twelfth century ce.9

Silk threads through the records of both my family history and place-based histories of Central Virginia, and over time illuminates parts of the evolving system of racial capitalism that Cedric Robinson describes. He argues that European capitalism extended the social logics of feudalism, which seized on and amplified antagonistic differences between socially and historically produced human groups within Europe.10 As Brian Williams and Jayson Porter summarise, ‘from its very inception to its daily reproduction, capitalism is dependent upon racism as a technology of division, coercion, and legitimation’.11 Robinson traces successive waves of players who formed early proto-capitalist classes and makes the argument that there was no literal or genealogical continuity between eras. He observes a continuity and elaboration of practices that fed on war and violence stoked by intra-European racialisms.12 He argues that this structured instability facilitated the rise of ‘opportunistic strata, wilfully adaptive to the new conditions and possibilities offered by the times’.13 Between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries, these early capitalists operationalised the imperial ambitions of the emerging nations-states based in Castile (Spain), the Ile de France and parts of England around London.

English imperial silk-profit aspirations brought both white mulberries to Virginia, and my first European ancestors to North America. In England, initial ambitions by King James I (reign 1603–25) to start an English sericulture were foiled by the cold climate: ‘having failed to raise silkworms in England, [he] urged the Virginia Company to promote the cultivation of mulberry trees and the breeding of silkworms in Virginia’.14 By the 1620s, King James I supported research on silkworm raising and ordered all settlers in Virginia to plant mulberry trees for silkworm rearing. Allison Bigelow argues that English Protestant monarchy and wealthy investors in the Virginia Company sought to strengthen England’s global economic position by diversifying from its singular dependence on tobacco in Virginia through sericulture, a ‘small scale industry that harvested colonial wealth and wove together different body politics in the name of common empire’.15 This vision argued for a transition from tobacco, a cured and perishable product, to raw silk.16

The same silk-laced English political and economic aspirations that brought Morus alba to Virginia also brought my European ancestors to North America. My earliest European antecedent17 in what is now known as the United States was my seventh great grandfather, Jean Durier (b. 1634),18 a French Huguenot who appears in English colonial land records in New Jersey in the late 1680s. Huguenots were a protestant religious minority, often skilled middle-class labourers who took up Calvinist Christianity. Colonial authorities saw Huguenots as having ‘southern European skills uncommon in England, most especially in the creation of valued Mediterranean commodities like silk, wine, and oil’.19

Anti-protestant violence racked France and other parts of Europe periodically before Durie’s emigration, and Robinson situates Huguenots within a broader pattern of Intra-European displacement and persecution that made people available for economic use ‘woven into the tapestry of a violent social order’.20 English Stuart monarchs who controlled New Jersey at the time viewed Huguenots as economically useful agents of empire who ‘forged a place in the world by advocating for a new kind of protestant imperialism’.21 Durier and his French compatriots’ ability to obtain British colonial land22 leaned on a growing trend in intra-European identity politics: French Huguenots increasingly identified as a people who held know-how of Mediterranean industries. Stanwood observes that ‘supplicants learned that they could open the coffers of the English crown by asking for land on the edges of empire and specifically by playing up their facility in producing silk and wine’.23 Durier’s identity as a Huguenot would have aligned his religious status with the economic desires of the nascent British empire, providing one of many useful paths ‘for the English and Dutch to develop their Empires without losing people’.24 It is through these movements, of a religious minority, and of a colonising aspiring world power, that both white mulberries and my European ancestors entered North America. Despite the designs of various English reformists regarding seventeenth-century agriculture, silk never became a major commodity in colonial Virginia where tobacco and later wheat came to dominate.25

This failure of sericulture to take hold, along with the relative invisibility of white mulberries and sericulture, stands in sharp contrast to evidence that white mulberries were far from a failure in terms of spreading across North America. Copenheaver and colleagues, who conducted a review of writings of eighteenth-century naturalists, found that, a century after these silk-colonisation efforts, Morus alba registered as the fourth most frequently noted non-native plant in John Bartram’s observations of farms and gardens in the Southeastern United States.26 Silk’s economic failure amid robust state and financial supports for sericulture by the British monarchy and colonisation companies point to the indeterminate27 nature of early Anglo-American empire. Aspiring profiteers cast nets wildly across all sorts of existing agricultural and husbandry traditions and experimented with potentially productive technologies, many of which (like silk) never took a real hold in North America. The history of US nation and empire is now often told in terms of destiny and fate, but the view via mulberries and silk shows England as an insecure power with imperial ambitions multiply invested in efforts to promote crops that now ‘rarely register in the region’s history’.28

Eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: Monoculture, plantations and nurseries

With the rise of large-scale field-based commodity agriculture in tobacco and wheat in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Virginia, mulberries largely recede from view. But two threads, the rise of planterly attitudes towards the management of agro-ecologies within systems of chattel slavery and the continued import of exotic plans through the emerging nursery industry, come into focus during this time, and provide key antecedents to the continued formations of categories of racialised peoples and invasive plants.

While mulberries continued their quiet spread in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the bulk of agricultural literature turned its attention to management of the plantation economy in Virginia, based in tobacco, wheat and associated animal husbandry. By the mid-nineteenth century, planters organised into agricultural societies that shared knowledge on ‘scientific’ farming practices that they published in periodicals, and lobbied lawmakers for legislation that supported agriculturalists.29

In periodicals like the Richmond-based Southern Planter,30 plantation masters described their farm systems as coordinated racialising assemblages,31 where the bifurcations of the human world in the white/Black racial order of chattel slavery were accompanied by a friend/enemy bifurcation of extra-human actors that played out in everyday farm management. Planters saw their farms as a collection of tiny wars, and their magazines show the primary management tactics with respect to productive life centred on the mirrored actions of care through war. Proper ‘care’ of the land involved the eradication and destruction of unwanted pests, weeds, water and any other environmental factor detrimental to the single-minded production of monocultural fields of staple crops. In this paradigm, human and non-human actors in the landscape could only be legible through their relationships to maximising yields and profits, neatly sorted into categories of beneficial and harmful.

One article entitled ‘Another enemy to the wheat crop’ expounds on these relationships with respect to known and unknown insects:

our farmers have all the plagues of Egypt upon them at once. Their corn crop is injured by the cut and bore worm, the wheat by fly, joint worm, and this stranger, who has found ‘local habitation,’ but is still without a ‘name’… This is a wormey age we live in, and we know of nothing better for a man to do than carry about with him a bottle of M Lane’s Vermifuge to protect himself against the prevailing epidemic.32

In this passage (and many others), weeds, pests and diseases were metaphorically described as enemies to be identified, isolated and destroyed with the newest technologies on the market. The mention of M Lane’s Vermifuge, then a heavily advertised 33 human anti-intestinal worm tonic, shows the direct correlation of human health and commodity crop health in the minds of plantation agriculturalists.

Relationships to plants were also couched in war-like terms. One planter writes to the editor about the application of lime as an early herbicide: ‘… I looked confidently for this effect, viz: the annihilation of broomstraw [a weedy native grass], but, as I said before, I was disappointed- the field, in another year, put up as thick a growth as ever.’34 Planterly imaginaries continually boxed relations between people and non-human actors into two categories: ‘friend,’ to be tended by fertiliser inputs and encouragement, or ‘enemy,’ marked for targeted elimination through weeding, poisons or other forms of death.

While this over-riding structure of bifurcation was constant, specific creatures often slipped back and forth between categories of beneficial and reviled. For example, one article discussed evolving proper planter attitudes towards red-winged blackbirds:

Red-winged Blackbird … has long been known to farmers as a sad thief … are great devourers of the Indian corn [but…] grub-worms, caterpillars, and various other larva- the silent but deadly enemies of all vegetation, and whose secret and insidious attacks are more to be dreaded by the husbandman than the combined forces of the whole feathered tribes together … If we suppose each bird on an average to devour fifty of these larva in a day … I cannot resist the belief that the services of this species, in spring, are far more important and beneficial than the value of all that portion of corn which a careful and active farmer permits himself to lose by it … we may justly claim for them the exemptions from the cruel assaults of idle gunners, [and] truant schoolboys.35

Here, the formerly ‘proper’ actions towards red-wing blackbirds were to kill them (with idle gunners, truant school boys, etc.), but the writer argues for moving these birds into the protected category of beneficial animals given their consumption of creatures (like worms and caterpillars) that were the true pests. Crop and livestock species’ value and worthiness for care was never in question, but all other human and non-human relations were understood in relationship to the desired products and dealt with via blunt choice between the logics of assimilation or annihilation. Metaphors also slipped between human and non-human worlds, personifying birds as thieves, tribes and servicers of corn.

Among people, the logic of class, and planter efforts to build white solidarity against the enslaved also functioned through the logic of care through war. Edmund Ruffin, editor of the well-circulated Farmer’s Register, in an address to the Virginia Agricultural Society spoke on the power dynamics of slave vs free labour:

This is the condition from which we are saved, and immeasurably exalted, by the subjection and slavery of an inferior race. The superior race here is free. In the so-called free countries, the far greater number of the superior race is, in effect enslaved and thereby degraded to a condition suitable only for a race made inferior by nature … In the so-called free countries … there is the slavery of class to class- of the starving laborers to the paying employers.36

In Ruffin’s rhetoric, there was no question that some category of humanity would be abused to drive the productivity of the plantation system. The only alternative to enslaving a ‘naturally inferior’ race of Black labourers who ‘deserved’ enslavement was the ‘unjust’ enslavement of white labour. Planters trumpeted this threat of racial displacement of abuse onto white men as the ultimate spectre of free labour regimes, attempting to draw a whole cadre of recently enfranchised propertyless white men into alignment with planter elites.37 The message to the white underclass living alongside the planter elite was, sustain the enslavers, or be enslaved themselves. Care for the systems of slavery or become the class whose lives are expropriated. As an inverse of the red-wing blackbird’s transition from foe to friend, human categories, too, could be placed under threat of change from protected ‘friend’ to enslaved ‘foe’: a reformulation of the same logics of systems requiring included and excluded categories.

While planters maintained crop monocultures to maximise productivity, display gardens of the plantation class showed prestige through the procurement and display of rare and unusual plants. Planters experimented with scientific farming practices like those outlined above, but also worked with the emerging nursery industry in northeastern port cities to elaborate a style of American landscape gardening that would rival gardening traditions in Europe.38 Charlottesville planters like Thomas Jefferson corresponded and traded with early nurserymen like William Hamilton of Philadelphia, and William Prince in Flushing, Long Island,39 and experimented with plants that originated across Europe and Asia.40

It was this network of plant procurement and sale that brought a second wave of Morus alba plants to Virginia. Prince’s nursery41 and others in Baltimore and Connecticut invested heavily in a wave of speculative excitement about Morus alba var. multicaulis, a ‘tree raised in China for silk culture … introduced into France by way of the Philippines’.42 Nurserymen sold the tree as a botanical wunderkind, purported to have a shrub-like multi-stemmed form and rapid growth that would support a robust sericulture in the Americas. An eruption of interest in silk-culture followed, with the organisation of state silk societies and the first national silk convention held in Baltimore in 1838, and various periodicals and farmer’s manuals exchanging information on mass multicaulis cultivation and silk culture.43

Near Charlottesville, the craze manifested on at least two sites: Morea near the University of Virginia, and Monticello, the former home of Thomas Jefferson. In 1834, Irishman and University Professor John Patten Emmet, built his estate on a 106 acre farm at the height of the multicaulis craze, and named it Morea in honour of the plant’s role as the ‘silkworm’s principal diet’.44 Emmet ‘succeeded fully, through his own ingenuity, in making sewing-silk of the best quality’, using silkworms fed on his multicaulis trees until his silk-making operation was destroyed in a fire. Later, he turned to grape growing and finding economic uses for a vein of kaolin clay he found on his land.45 Contemporaneously, a local man, James Barclay, bought Thomas Jefferson’s estate at auction for $7,500 ‘for a scheme that would turn Monticello into a silkworm farm. In order to plant mulberry trees, Barclay tore out many of the trees Jefferson had planted and uprooted the extensive gardens.’46 He sold the farm three years later at a dramatic loss.

Like other multicaulis speculators, both Emmet and Clay ultimately failed in their attempts to make mulberry cultivation and silk culture profitable, but Emmet’s biography in particular illustrates the movement of a racialised group in Europe to the position of planter and/or coloniser in North America, ultimately becoming enfolded into the category of whiteness in the US. Emmet, born in Ireland and nephew of a prominent Irish nationalist, would have been part of the Irish influx to the US, hailing from a region that had been colonised by the Tudor England contemporaneously with Virginia’s Jamestown, and then forcibly settled by the Stuarts with Protestant planters from Scotland.47 Ignatiev observes that, by the mid-nineteenth century, Irish transplants to the States were increasingly casting off their racialisation, but while ‘white skin made the Irish eligible for membership in the white race, it did not guarantee their admission; they had to earn it’.48 Emmet’s taking up of ‘aristocratic’ Virginian practices, like using enslaved labourers,49 and his entry to the faculty50 at the University of Virginia reflect his position as part of the leading edge of the Irish’s improving status and growing power in larger political alliances in national politics that tied ‘the assimilation of the Irish into the white race [that] made it possible to maintain slavery’.51

In general, the multicaulis craze was another in the line of silk’s economic failures in the US, as by 1840, it became clear that the Morus alba var. multicaulis was not hardy in the North, and nor did agriculturalists in the US have the capacity for the seasonal nature and painstaking processes of worm-rearing to transform leaves into silk. Like England before it, ‘having failed in the raising of cocoons, the American silk merchant turned his exclusive attention to manufacturing’.52

Turn of the century: Industrial silk, ‘foreign’ pests and empires

It is also the in mid-nineteenth century that the history of my Japanese family collides directly with the racial and economic story of the United States. On my father’s side, the family’s already considerable wealth exploded with my third great-grandfather, Jokichi Ujie, who positioned himself to sell silk eggs to Westerners53 after Commodore Perry’s forcible ‘opening’54 of Japan by gunboat diplomacy in 1853. My third great grandfather’s silk egg operation sold ‘seeds of silkworms to foreigners in Yokohama … made a big profit. His workers put silkworm seeds in carts and carried them from Kakuda to Yokohama by horse.’55 My ancestors happened to ride a rapid boom in the Japanese silk egg industry. This boom was a result of twin supply crises that were crippling the European silk industries in France and Italy: pebrine (Nosema bombycis), a silkworm-killing fungal disease spread on mulberry leaves,56 and the Taiping Rebellion in China that disrupted Asian raw silk production and cut the European supply to pebrine-free silkworm eggs.57 These two disruptions meant that ‘Japan became the sole supplier of the whole Mediterranean sericulture’58 for a brief moment in the mid to late 1860s, taking my family to a level of wealth that wasn’t whittled away until my lifetime. Carl Wilhelm Von Nageli’s identification of the pathogen and Louis Pasteur’s findings on pebrine-prevention worm cultivation methods led to a recovery in European silk culture,59 and a collapse in the Japanese silk egg industry by 1875.60 Japanese sericulturists ‘turned their attention from the production of silk eggs to this new field of raw silk production for American markets’.61 Japan and the US quickly developed a robust bilateral trading relationship, wherein raw silk dominated Japanese exports from 1870 to a peak in 1925.62 These exports supplied a burgeoning US silk manufacturing industry, centred primarily in Paterson, New Jersey and, later, eastern Pennsylvania.63 Shichiro Matsui notes that the late-nineteenth century silk boom in the US was due to national and global factors. The levying of silk duties on imports to the US during the Civil War spurred domestic production, the opening of inter-Pacific shipping in 1867 and the completion of the Transcontinental railroad in 1869 provided a path for importing Japanese silk to the East Coast, and the Franco-German war of 1870 slowed production of silk in Europe, opening a window for profitable domestic silk manufacture in the US.64

In Virginia, silk factories emerged during this era and, while they barely register in broader histories of the American silk industry,65 silk factories are a major player in the story of the land development in Charlottesville. Local capitalists, looking to expand production from a mill that had processed local wool into fabric since before the Civil War, expanded into silk fibres by erecting the Armstrong Silk Knitting factory just north of downtown, and operated there until the cusp of World War II.66 In 1928, New Jersey silk manufacturers Frank Ix and Sons opened a silk mill on a large site on the south side of town,67 which became one of the city’s biggest employers before its closure in 1999.

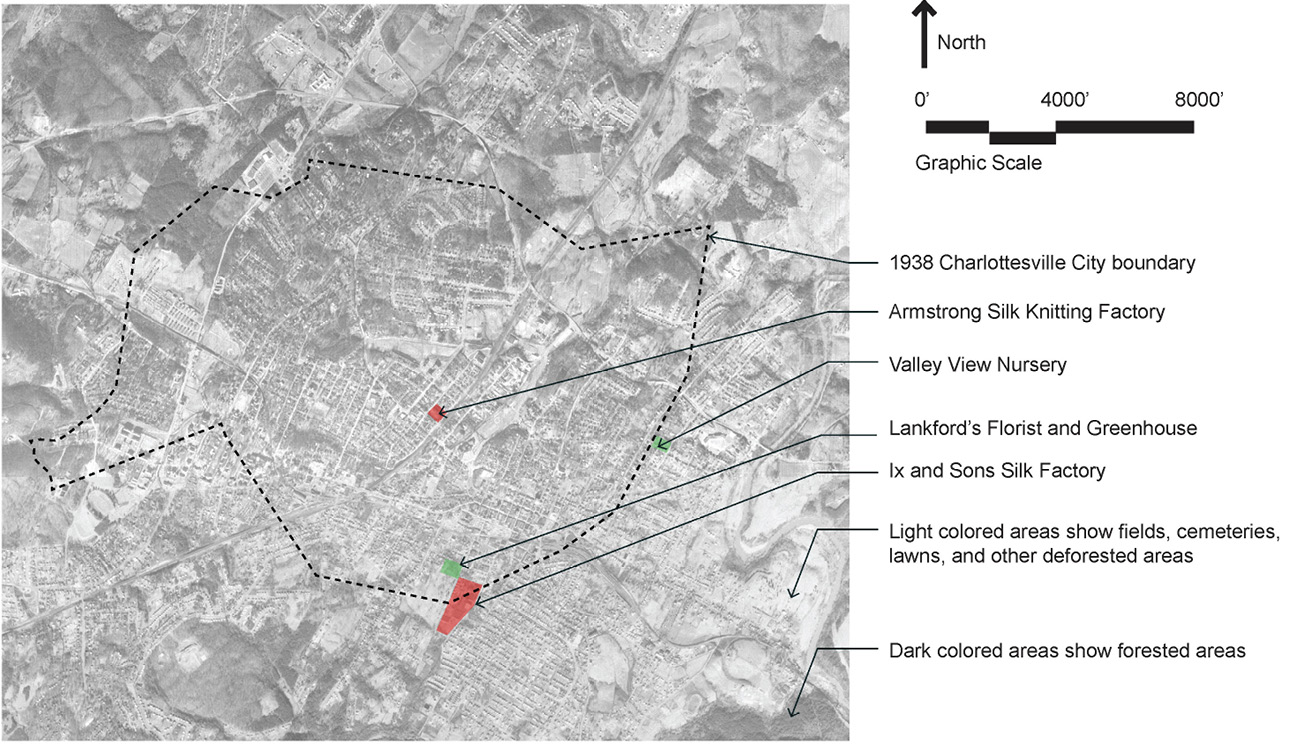

Figure 1.

Mid-century Charlottesville composite map.

Sources: 1959 USGS aerial photographs of Charlottesville Area and city directories. Overlay map created by author.

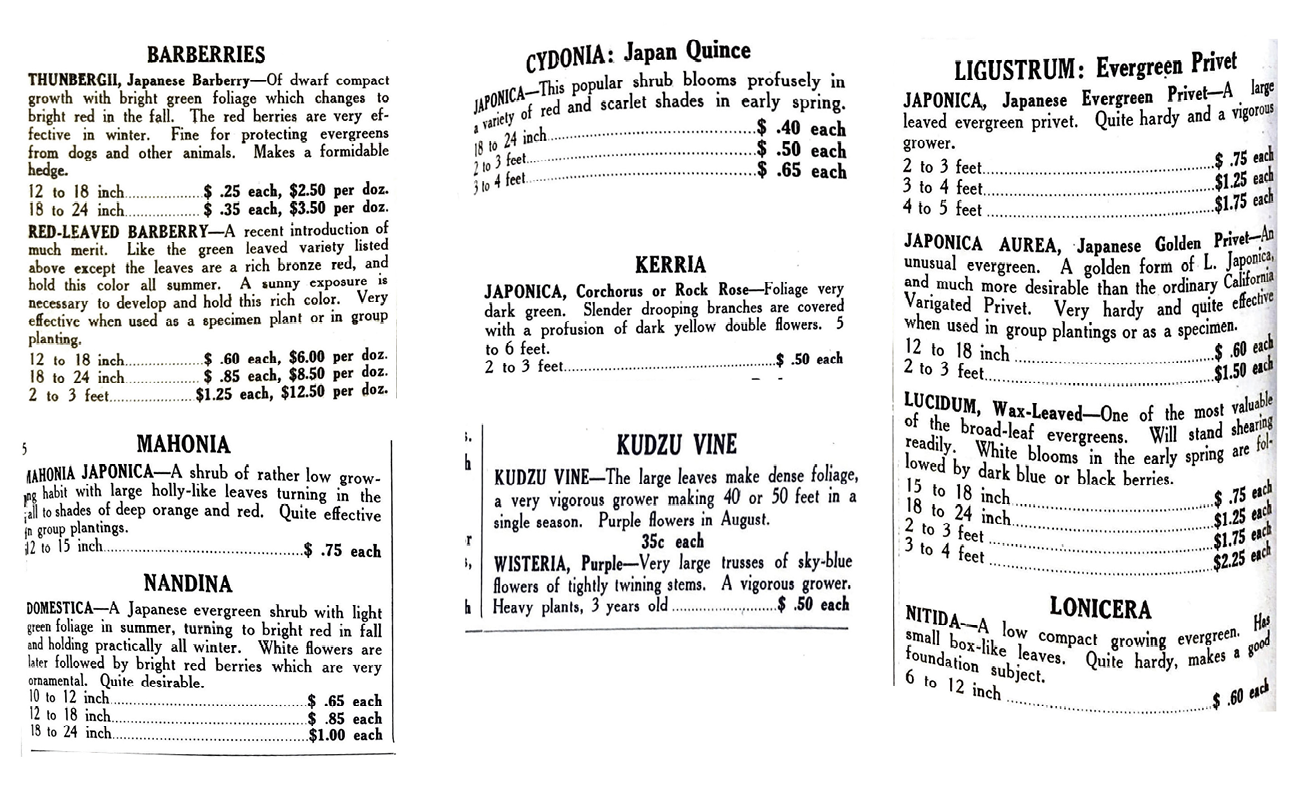

The combination of urban industrialisation and continued plantation-like agrarian practices produced both denser human settlement around Charlottesville, and a widely deforested agricultural landscape in the surrounding areas (Figure 1). By the early-twentieth century, the agricultural lands around Charlottesville produced commoditised field crops, orchard products and livestock for meat, dairy, fibre and horseracing. In a landscape that had historically tended to produce a forested ecology,68 this management regime produced tilled and disturbed nutrient-rich soils that provided many opportunities for weedy plants to thrive. Large-scale monocultural plant stands in orchards and fields provided a haven for plant diseases and pests. At the same time, nursery traders expanded to serve the growing local ornamental market in suburban gardens, as more local nursery growers sprang up to supply exotic (often Asian) plants to local home gardeners (Figure 2).69 Many of the plants noted as of Japanese origin shown in the nursery catalogue pages in Figure 2, including barberry, honeysuckle, kudzu, mahonia, nandina and privet, are considered invasive in the region today.

Figure 2.

Charlottesville’s Valley View Nursery catalogue excerpts – Japanese and other Asian ornamental plants, most shown here are considered ‘invasive’ in the present day.

Sources: 1932 Valley View Greenhouse Catalog (held at University of Virginia Special Collections Library).

Meanwhile in Japan, economic and military power built on silk exports positioned the nation to become a dominant power in the region with Western backing. Japan was an early adopter of multicultural and neoliberal forms of racial capitalism, hiding and disavowing its own colonial brutalities and violences under the umbrella of Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. It was under this banner of ‘co-prosperity’ that Japanese imperialists before World War II claimed they were ‘freeing’ colonised nations from Western influence, and ‘civilising’ ‘backward’ nations and remaking them in the image of the Asian ‘superior’ Yamato Race.

In this context of heightened trans-Pacific trading and exchange, and the growing imperial aspirations of both the US and Japan, agricultural systems became a setting where a host of players elaborated the connected sciences and ideologies of monoculture agriculture, pest control and racialisation. Approaches from plantation agricultures of Virginia flowed into the stream of nationalised US agricultural institutions and policies through the formation of the United States Department of Agriculture and the 1862 Morrill Land Grant Act, which laid the institutional groundwork for land grant colleges, agricultural extension agencies and state experiment stations. Lyman Carrier shows that southern antebellum state agricultural societies, including Virginia’s, were major proponents of these two federal structures, and that the USDA was in many ways a functional successor to those state-level networks.70 Some early officials of these agencies hailed from Virginia, and would have carried ideologies about the necessity of crop monocultures, racist social frameworks and desires for extermination of their environmental enemies into the dominant industrial agricultural practices of the US.71 In relation to the Western US, Jeannie Shinozuka highlights the expansion of field crops and orchard monocultures into California’s Central Valley and other major agricultural regions of the American West, which interacted with a now-robust nursery trade that nurtured and spread plant pests alongside horticultural stock across the world. She argues that the expansion of crop monocultures, white racist and nativist attitudes toward Japanese and other East Asian immigrants, and the explosion of novel insect, fungal and bacterial pathogens encouraged by monocultural stands of vulnerable plants brewed a regulatory culture in the USDA that associated non-human pests with human racial groups including the Japanese and Latinx populations.72 She describes the racialisation of various biotic pests like the San Jose scale, chestnut blight, citrus canker and Japanese beetle, which often had geographically unclear origins73 as ‘Oriental’, arguing that agricultural pest management was a major venue where ‘environmental enemies’ of crop pests were associated with Asian-ness. And, through the networks of nurseries that spanned the East and West coasts, San Jose scale, one of the first insects to produce a concerted response from the USDA in California where it had been known since the 1870s, ‘appeared in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 1893, threatening all orchards in the East’.74 Racial logics of confinement and annihilation spilled over between human and insect, consolidating an over-arching narrative of biotic and human ‘yellow peril’ that drove the rise of both plant quarantine and control laws,75 and human immigration control laws76 of the early-twentieth century.

At the same time as doors closed on Asian immigration to the US, doors were opening to European-descended American ethnic populations in the late-nineteenth century, in a wave that Nell Painter calls the second enlargement of American whiteness.77 Silk and other industries provided one road to wealth that my European descendants rode, claiming stable industrial jobs through much of the twentieth century. Two of my distant European immigrant cousins were men who married Durie women, and held long careers in silk work in New Jersey and New York. 78 Another path to white wealth was through seizure of land from Indigenous people. My second great grandfather Durie married a Scots-Irish woman from Maryland, and they claimed land in what had recently been Indian territory in the Oklahoma land rush in the late-nineteenth century.79 Much as Jean Durier came to the New Jersey colony as a religious refugee and potentially productive tool of English empire, my second great grandmother came from people displaced and re-placed in various English land grabs. In the seventeenth century, the crown recruited ‘“surplussed” Scots tenants and cottagers’ to English-colonised Ireland as ‘the main bulwark of social control over the dispossessed native Irish chiefs and lords and their tribes’,80 and then again to the American colonies to inhabit the Indigenous lands west of the Appalachian Mountains.81

By the late-nineteenth century, my European ethnic ancestors were building social and economic power and ‘improving’ their position in American racial projects.82 As they landed industrial jobs and stolen lands, acquisitions that were largely barred to other racial and ethnic groups, they began taking up Anglo-American practices of genealogy and organising along lines of descent. Francesca Morgan makes the connection between origins of hereditary organisations like these and anti-Asian xenophobia: ‘In the 1870s, San Francisco was simultaneously a seedbed of hereditary organizations ... and of mass demonstrations for Chinese exclusion’.83 The formation of Huguenot (1883),84 New Holland (1885)85 and Scotch Irish (1889)86 societies nationally, accompanied a new proliferation of American-European ethnic history texts.87 Through these texts and societies, ‘ethnic’ European groups claimed narratives of ‘firsting’ by showing that the Huguenots and Scotch Irish were integral to the colonisation of the United States.88 This revisionist history wrote white ethnics into the origin stories of the nation, and refuted Native American claims to land by picturing their extinction in the contemporary US.

Mid-twentieth century: War, chemicals, racism and invasives

World War II heightened both the racialising rhetoric of war as care and the technological capabilities of this type of world-making in the US. In 1941, chemist R. Pokorny reported the synthesis of a new compound, 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, better known as 2,4-D in the Journal of the American Chemical Society. Plant scientists at the University of Chicago and USDA Plant Industry Station in Beltsville, MD, turned their agriculturally-focused testing of herbicides to military uses for the war effort in the early 1940s. By November 1942, the Army established Camp Detrick, in Frederick, Maryland as a ‘research and testing centre for the recently initiated biological warfare program [… and made] herbicide research part of the work at Camp Detrick’.89 By 1944, extensive military tests of various chemicals as herbicides began to home in on 2,4-D as a compound that selectively killed many broad-leafed weeds in agricultural and lawn settings.90 Agricultural applications of herbicide tests were not held secret like military applications of chemicals, and, by 1945, chemical companies were selling 2,4-D to American consumers, first as American Chemical and Paint Company’s (ACPC) brand ‘Weedone.’ Production of 2,4-D exploded, from 917,000 pounds produced in 1950, to 53 million pounds by 1964.91 2,4-D ‘started weed research on its way as a full-fledged new science … all types of scientists … jumped into the whirlpool of activity engaged in trying to learn more about this magic new chemical weed killer and about the whole field of new herbicides opened by this discovery’.92 With this introduction of cheap herbicidal chemicals, weed control, which had ‘remained a relatively minor phase of agronomy, botany, horticulture, agricultural engineering, and plant physiology’,93 exploded into the mainstream of these sciences. As one measure of the proliferation of interest in chemical herbicides, in 1943, only 69 articles in the USDA’s bibliography of agriculture focused on weeds, while, by 1949, more than 600 concerned weed control.94

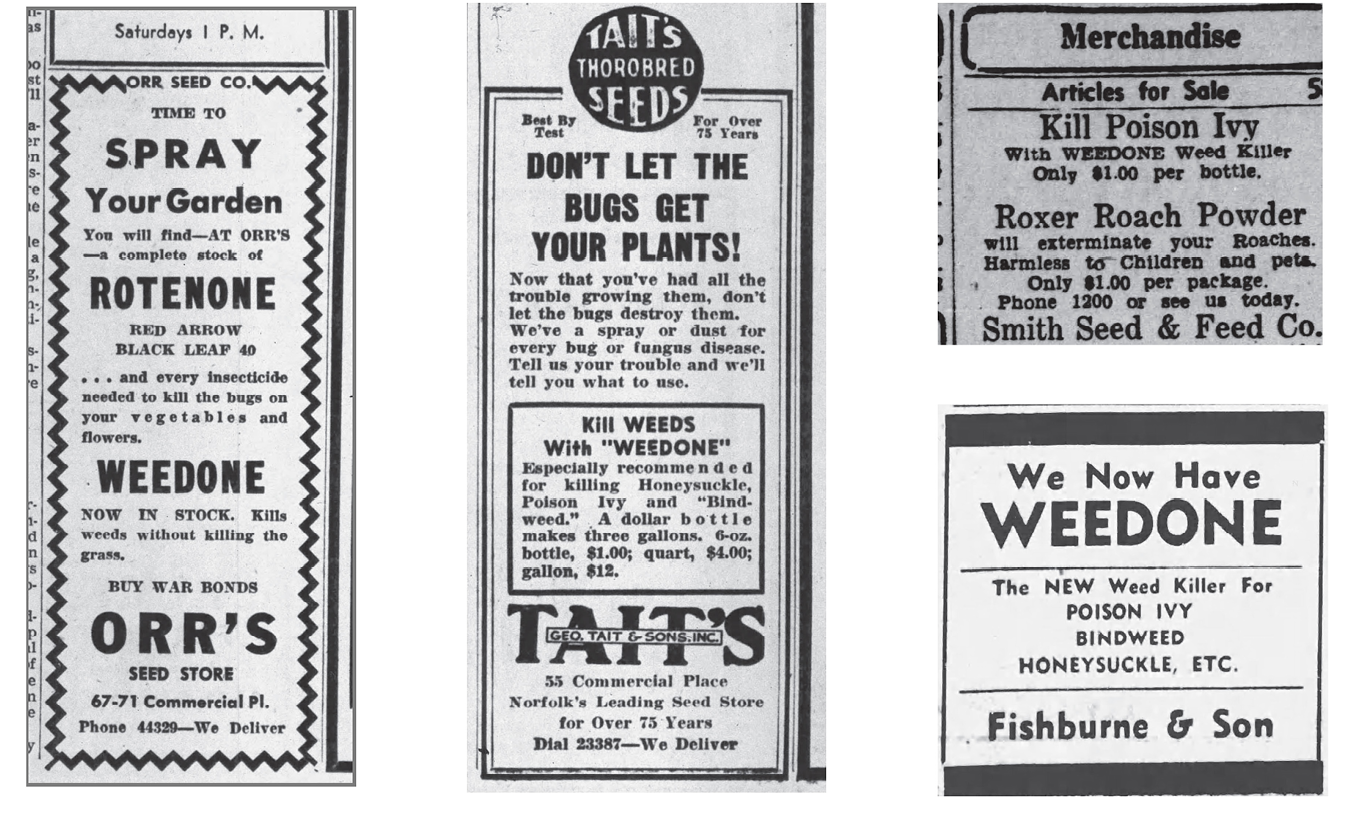

Virginians, according to the documentary record, joined the ’great popular interest in the herbicidal potential of 2,4-D’.95 Advertisements in Virginia newspapers for ACPC’s ‘Weedone’ weed killer marketed 2,4-D to gardeners during the war alongside existing insecticides and fungicides.96 Wartime rhetoric expanded and reinforced logics of care through pest extermination to the lives of plants. (Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Virginia newspaper articles selling ‘weedone’ and other anti-pest chemicals.

Sources: from left to right and top to bottom, ‘Orr Seed Co’, Norfolk Ledger-Dispatch, 18 May 1945; ‘Tait’s Thorobred Seeds’, Norfolk-Ledger Dispatch, 17 May 1945; ‘We now have Weedone’ Waynesboro News-Virginia, 13 July 1945.

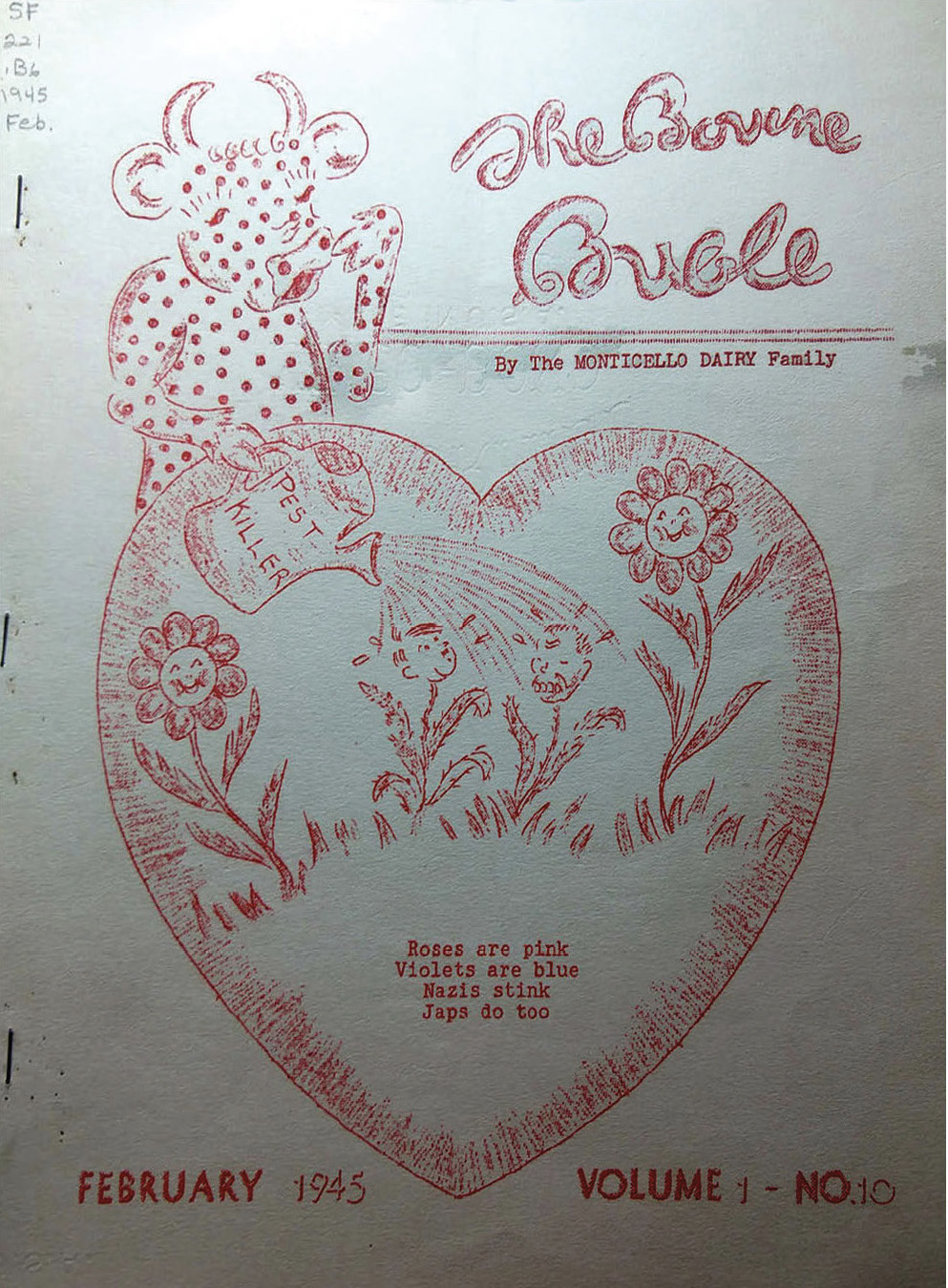

Much as metaphors of care through the annihilation of various creatures slipped back and forth between tribe, army and non-human creatures in planter magazines from the 1850s, in wartime popular media, plants, pests, and racial categories of people folded together. In one example, Charlottesville’s Monticello Dairy’s monthly employee newsletter, the Bovine Bugle, released cover art in February 1945 that depicted their bovine mascot dousing two anthropomorphised weeds described as ‘Nazis’ and ‘J*ps’ with ‘pest killer’. (Figure 4)

Figure 4.

Cover of the Bovine Bugle, Feb. 1945.

Source: University of Virginia Special Collections.

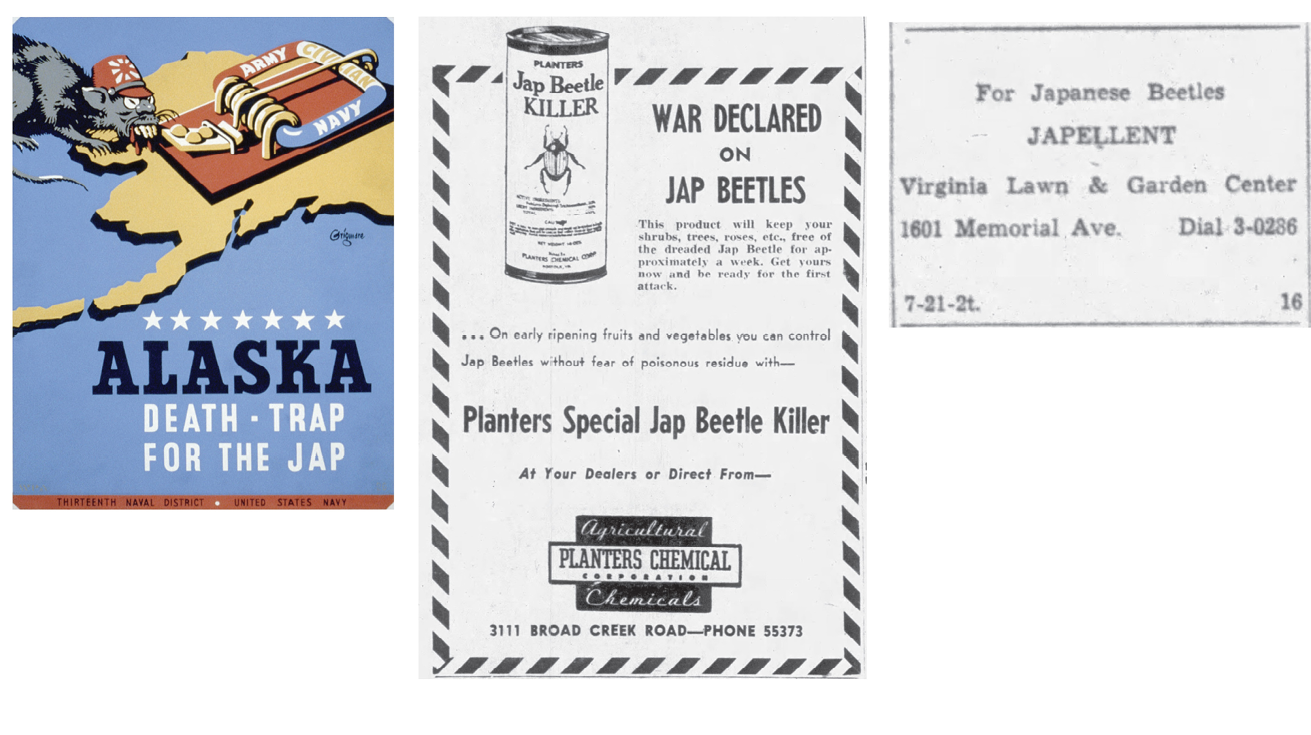

While the German ‘weed’ was topped with Hitler’s face, the cartoonist depicted the Japanese ‘weed’s’ face-flower as a generic stereotypical Asian man, depicting the entire Asian racial category as ‘weed’. This imagery of the Japanese pest requiring extermination lived on well after the war in advertisements in chemicals for extermination of Japanese beetles in gardens and agricultural lands.97 (Figure 5)

Figure 5.

Japanese people, Japanese ‘pests’.

Sources: left to right – Edward T. Grigware, ‘Alaska-death-trap for the Jap’, silkscreen on posterboards, Washington: WPA Art Project between 1941–43, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/98510121/; ‘War declared on Jap beetles’, The Norfolk Ledger Dispatch, 14 June 1950; ‘For Japanese beetles Japellent’, The News, 22 July 1953.

These continuing messages about the ‘foreign’ threat of ‘Asian’ organisms helped supercharge the demand for existing herbicides, and myriad new herbicidal chemicals that entered the market in the second half of the twentieth century.98 The capabilities of these chemicals also opened a window to the expansion of government regulation around the controlling the movement and requiring the eradication of ‘foreign’ plants. Chemical companies previously in the business of wartime chemical fabrication pivoted to domestic uses in agriculture and land management and leveraged new federal policy to steer governmental and private land management toward pesticide use. While present-day messaging around ‘exotic invasives’ centres on the ecological impacts of weedy plants, the first federal legislation on controlling the movement and spread of weedy plants, the 1974 Noxious Weed Act, instead focused on losses to the agricultural industries due to weeds introduced to the US.99 In mid-century, the rising mainstream environmental movement picked up these metaphors of foreign plant invaders to be eliminated,100 popularising herbicide-based land management practices beyond the farm. By 1999, President Clinton signed Executive Order 13112 ‘to prevent the introduction of invasive species and provide for their control and to minimize the economic, ecological, and human health impacts that invasive species cause’,101 and created a coordinating body – the Invasive Species Council (NISC) – to oversee implementation of the order. The 2004 amendment to the Plant Protection Act of 2000 charged the federal government with establishing ‘a program to provide financial and technical assistance to control or eradicate noxious weeds’.102 Tao Orion notes that these policies embedded herbicide company interests in governmental systems for weed control by funding university research that explored chemical weed control, allowing individuals from the pesticide industry to sit on important national and state-level invasive plant councils that did long-term planning for weed eradication at various levels of government, and directly funding pesticide application. She also points out that herbicide company influence reaches beyond governmental systems, as industry representatives hold important advisory positions in large non-profit entities like the Nature Conservancy, steering their massive land management programmes towards increased pesticide use and company profitability.103

Drawing lines to the present

During my lifetime, my family’s biggest wealth-building assets have been land and single family homes, including the one my partner and I bought in Charlottesville in 2009. In terms of the value of the land that I purchased, I can trace the passings of this land all the way back to the same English colonial projects that brought mulberries to Virginia and Huguenots to New Jersey. When I became a property owner, I joined the genealogy of property, which directly connects me through acquisition of this plot to the Euro-North American tradition of territorial expansion through violent seizure, and the holding and leveraging of land held at the household level for the exclusive use of the property owner. Looking back at this history of Euro-American land development and territorial expansion, I can understand how this particular 0.2-acre parcel’s value has been negotiated, layered and elaborated through seizure of lands inhabited by Monacan people, 104 successive systems of chattel slavery, monocultural agricultural production, residential segregation and suburbanisation that expanded structures of wealth-building through homeownership to a broader segment of the American populace. My neighbourhood is still called ‘Locust Grove’, after the plantation held by George Sinclair in the mid-nineteenth century. Land companies of the late-nineteenth century105 and real estate agents today continue to mobilise the pastoralist overtones of its plantation past to signal its desirability. I can read my family history on mother’s side as a process of the sedimentation of the layered constructions of whiteness through inheritance, and actively enforced spatial practices of racial boundary-making.

My mother was born in Rockport Missouri in 1952 to a middle-class family who saw themselves as white. As with many families living in Charlottesville’s Locust Grove in the 1950s, my mother describes her upbringing, and her family’s upward mobility evidenced by the family’s move from a rental to owning their own home. Her parents were both teachers, with her father’s credentials gained from GI bill funded education after World War II,106 programmes that systematically and disproportionately benefitted white veterans, and excluded Black servicemen in education, home loans, and unemployment insurance.107 My mother’s paternal great-grandfather, as Sheriff of Grant City, served as an enforcer of racial-spatial rules in their small Missouri town. Other relatives informally patrolled the city as a sundown town:

And Grant City ... your Grandfather used to emphasize this. When he was a kid, EVERYBODY. Everybody knew that places like Grant City were called sundown towns. That meant if you were in that town and people didn’t know who you were, or you looked funny to them, you had to get your ass out of town by sundown, now they could take care of it themselves ... There was one Irish Catholic in the family who married my grandfather Clouse’s sister. He was a very sweet man, but he was also extremely prejudiced, OK? ... And my uncle Ray who was an Irish Catholic and had become kind of part of the group...I remember him bragging about that kind of stuff. He had a gun and yeah. He’d say, yeah if there’s somebody that comes through here, and we don’t like him? We’ll take care of that... 108

This passage speaks to the dynamics of my family, where connections to older ethicised traditions like the mantle of a questionably ethnic ‘Irishness’ were actively cast off, and social networks reconstituted through racialising processes. The price of belonging became assimilating into the ranks of the enforcers who policed the colour line.

On my Japanese side, my third great-grandfather’s early success in silk eggs positioned his sons and grandsons to become leaders in local industrial development109 and politics. My second great-grandfather was the President of Kakuda Ice Manufacturer, CEO of Tohoku Ice Maker, and a major landlord. He sat on both town and city councils. My great Grandfather was an art collector, and local ‘philanthropist’ in the Kakuda area, and the family’s main home is now a museum. These stories, while still out-of-focus and incomplete without further research in Japanese archives, eerily signal the parallel lifeways my Japanese ancestors were turning toward that mirror the actions of powerful local leaders here in Charlottesville. They turned toward liberal democracy, toward industrialised supply chains and towards the self-aggrandisement of lineages that claimed culturally high ground in social dynamics of urban formation. In the American-led post-war building and industrialisation boom that defined my father’s coming of age, it was my family’s silk-threaded wealth that allowed him to go to college where he studied with my mother, and to join the American professoriate, teaching Japanese to American business majors in the 1980s.

Conclusions and openings

Through this exercise of tracing the examples of person (my genealogical history), place (history of Charlottesville, Virginia) and plant (history of Morus alba), the repeating patterns and practices of racial formation110 in the service of profit accumulation become visible across the succession of waves of globally structured migration and displacement that have crossed Charlottesville and my family lines. As Justin Gammage notes in his exploration of the history of labour-based Black organising in Philadelphia, ‘Capitalism’s foundation mandates an exploited class, largely made up of marginalized communities’, and the structure of hierarchy remains even as the terms of who sits in what positions changes.111 The particulars of the favoured commodity crop versus the useless weed, and of the racial and social status of various immigrant populations (Huguenot, Irish and Asian) shift dramatically. But we can also see what does not change: that immigrant populations are made materially vulnerable, exposing people to precarity used to recruit these groups to enforcing their relative privilege through the maintenance of persistent anti-blackness.

A line of my own personal experiences in this Euro-Asian-American body evidences further turns in the chameleon forms of the systems of racial capitalism. I remember the seething anti-Asian schoolyard taunts from a childhood in Boston in the 1980s, and contrast that open hostility with the institutional embrace of an employer touting my presence on their roster as evidence of the design firm’s commitment to racial and gender diversity in the 2000s. I can track these experiences against Jodi Melamed’s periodisation of post-World War II US racial projects, and see in my experiences the rise of what Jodi Melamed calls neoliberal multiculturalism. She notes that, by the 2000s, dominant narratives of US exceptionalism used the sparse presence of minoritised individuals in the halls of power to supercharge the American myth of equal opportunity. The appearance of institutional diversity became an instrument to pathologise people seen as monocultural as backward, rationalising the social tolls of dramatic rollbacks of the mid-century welfare state.112 Today I find myself interpellated as a mixed-race subject: evidence of parental ‘love that sees no color’, a label that uses old eugenical logics of bloodline to exceptionalise mixing,113 calling me into the project of pathologising those who are exploited by neoliberalism’s structures. Meanwhile, today’s language and management practices regarding Asian invasive plants and pests serve as a repository of the racist xenophobia that haunts the margins of everyday life, ringing in my ears as evidence that beings who are pictured as like me in their Asian-ness are annihilatable. These experiences are like so many invitations, like those posed to my ancestors before me, to align ourselves with the anti-relationalities, alienations and the violences of racialising market systems. But there are other paths to turn towards if we again retell relations between human, plants and land.

First, tracing my family lines in this piece shows that the dominant (and therefore easily accessed) ways of keeping records and family stories highlight those who aligned with the aims of projects of capital accumulation and cultural assimilation. Their stories were held so close by my family insofar as they were useful in the present.114 Howard Ira Durie, who wrote the genealogy of the Durie family in 1985, came of age at the height of white ethnic genealogical self-description’s cultural cachet in the early-twentieth century. The Durie genealogy tied the numerous present-day descendants of Jean Durier to a home deemed to have historical value by the New Holland Society, chaired by then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1936.115 It is this first Durie home I have photographs of my own beloved grandmother visiting in her retirement. It was my sense that she went there because she longed to know where she was from. But it was Jean Durie’s appearance in the written record of land holding that valorised him as a ‘first’, that drew the thread of his particular line to the family forefront and sanctified his colonial home as a place of family pilgrimage. These particularities of power made Jean Durier the exemplar of where my family was ‘from’ during the twentieth century. But this reframing of the stories through which my family understands itself loosens my grip on Jean Durier as a significant progenitor, as a useful past for the present. Perhaps with the changing present, the context of ecological and social crisis brought about by the systems of accumulation that made Durier our primary figure, we can and should attend to other threads in our lineages that may not be so decipherable. I am not seeking an alibi for the ways my antecedents participated in the historical construction of whiteness and the violence underlying its benefits. A reckoning with that legacy is part of what spurs the current article. But Jean Durier was only one of 512 of my ancestors in his generation, and the centrality of his ‘success’ hides both the complexities of his story and the hundreds of other stories, traditions, habits and lifeways that might be useful origin points for today’s narrations of where we come from and where want to go.

Second, physical and botanical environments hold evidence of the ongoing failures of systems of domination and profit-making, even as paper archives and familial and cultural stories of origin retroactively work to picture their inevitability. Attending to the land and the plants in these stories points to pathways occluded by these linear narratives and their foregone conclusions. My grade-school history class, museums and historical sites pictured colonial English settlers of Virginia destined for greatness.116 But the mulberry’s presence marks the persistence of silk’s failure as a home-grown commodity. The story of silk shows the Virginia Company as a fragile entity, with investors desperately grasping for any possible mode of growing profits in a place where they had almost no sense of how to do so. Later, plantation masters appear as foolish investors who lost their shirts on a plant that would not do what it was intended to do. The failures of silk in Virginia punctures a retroactively teleological narration of settler and plantation success, opening a crack to an always-available historical indeterminacy.117 Now, I see the mulberry as a living portal to the sense that a lot more has been going on here, and perhaps alternative trajectories can be recovered for surviving, countering or resisting structures of domination rather than amplifying them.

Last, a physical question: since the mulberry failed to become economically central, its story has fallen out of historical consideration in Virginia, but what has the plant been up to? Tao Orion argues that invasive species are the symptom rather than the cause of the biodiversity loss that is the crux of the anti-invasive logics. The deeper causes of habitat loss are both the present human habits of mass land disturbance which favour weedy species like mulberries, and the 200 million acres of land planted in the equally non-indigenous monoculture crops of wheat and soy in the United States.118 And from this exploration of the origins of plant invasiveness, we see that the pre-existence of a wartime chemical companies turned herbicide mega-manufacturers have leaned on the xenophobic habits of mainstream American culture to lend a moral urgency to highly profitable programme of herbicide-based invasive eradication.

The cultured response to see an invasive plant and seek to only to murder it119 shortcuts any collective inquiry into its histories and other aspects of our present and historical relations to it. Attention to the plants, people and land in right front of us lets us attend to the things that our current cultural habits labour continuously to draw us away from noticing, both in terms of the larger historical legacies driving our current circumstances and of the alternative trajectories and solidarities that could emerge.

A few examples among many that are possible, if we really drew on what we could learn. First, Tim McCain notes Morus’ edible berries are likely to have attracted early humans to the plant and this human proximity to the plant’s edible parts may have introduced us to silk-spinning caterpillars in the first place.120 This opens a historical tradition of direct, metabolic relation to our surroundings that commoditised staples and industrial food systems have required us to forget. Second, from historical angles visible only obliquely in official sources, the hedgerows, forests, swampy and other uncultivated lands were likely the places where ‘useless’ trees like mulberries might have grown unbothered. Many scholars of the Antebellum South observe that these were spatial settings where enslaved people held camp meetings, surreptitious gatherings and eluded, if momentarily and incompletely, the surveillance regimes of the field.121 If we turn away from seeing a tree as an alien to be cut out, perhaps we can recover its role as spatial accomplice to the rival geographies122 of people living under a kind of extreme domination that echoes into our own time. In more recent memory, Alexis Nicole Nelson (@Blackforager)123 drew on her own and many other peoples’ longing for connection during the isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic by combining public education about the legacies of land, enslavement, and vernacular food traditions with practical explorations of the edibility of common North American plants. Nelson’s work pointed to one avenue to lifeways of metabolic redundancy amid the huge systemic failures of pandemic response in the United States. For me, her demonstrations with plants resonated with an opening that the pandemic highlighted: what systems of relation do we need to build to sustain ourselves amid the dramatic shifts we are witnessing as today’s historical actors? And what resources do we already have to explore these necessary ways of living?

To close, in one of my recent foraging outings, I found myself in the company of an East Asian elder who ran a local Vietnamese eatery, who smiled as we both picked mulberries near a public riverside walking trail.124 I wondered if he, like my Dad, who emigrated from Japan, recognised many ‘invasive’ weeds as familiar culinary friends from Asia when he arrived in the US.125 A blonde woman walked by and commented that she hadn’t eaten mulberries since she lived in France. I wondered, wait … did the Duriers eat these too? After all, my family lore remembers that Durier meant ‘dwelling by the river’,126 pointing to some point in time when relations to the places they lived were so important that peoples’ names emerged from them. By the river, the same sort of setting I was standing in today, eating from a stand of trees which were here via an ancestral transit from East Asia to France to the US, from forest, to cultivated working tree, to weedy hedgerow, to invasive, to what will be next? My body hummed with tasting (remembering?) so many connections to people, places, and lands, even as I will never know most of the stories of what this flavour could mean.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to my dissertation committee Kwame Otu, Tony Perry, Beth Meyer and Barbara Brown Wilson, who commented on the first version of this paper when it was the last chapter of my dissertation. Thank you to Andrea Pitts, Meredith Palmer and Alexandra Judelsohn (Fall 2023 UB new faculty writing group) and Malcolm Cammeron, Thomas Storrs, and Jacqueline Sahagian (UVA urban history writing group) for accountability and conversation that informed this paper, and to Jayson Maurice Porter for conversations across art and writing that supported this work. Thank you to Colleen Brennan and Leah Kahler, students who found the Valley View Nursery Catalog in UVA Special Collections Library, and to Jordy Yager of the Jefferson School African-American Heritage Center in Charlottesville, who partnered with my Architectural History Field Methods class that sent students there. Thank you to my parents whom I interviewed for this work in the deepest days of COVID lockdown, and to Theo, Peter and June for the support and love. Finally, thank you to the land and the mulberry trees who continue to productively shift my path.

Alissa Ujie Diamond’s work focuses on histories of spatialised inequity and action-research as a basis for systems change in the contemporary world. As an interdisciplinary scholar, she draws on an early career in applied architectural and landscape design as well as scholarly frameworks from environmental history, geography, plant humanities, urban planning and ethnic studies. Her historical research focuses on racial capitalism and spatial development, probing how social hierarchies have been produced through city-building practices and structures, and how these uneven processes of extraction reach into the present. Her future-facing work focuses on historically-informed and community-driven research for intervention in current institutional systems. Finally, she draws on her background as a designer and artist to develop methods for engaging art and making to build solidarities and shared historical understandings of place and people.

Email: ad97@buffalo.edu

1 Jil Swearingen et al., Plant Invaders of Mid-Atlantic Natural Areas: Revised & Updated- with More Species and Expanded Control Guidance, 4th edition (Washington D.C.: National Park Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2010), pp. 89–90.

2 Jason W. Moore, Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital (London, New York: Verso, 2015).

3 Andrea Roberts and Grace Kelly, ‘Remixing as praxis: Arnstein’s Ladder through the grassroots preservationist’s lens’, Journal of the American Planning Association 85 (3) (2019).

4 Examples include Donald Edward Davis, Where There Are Mountains: An Environmental History of the Southern Appalachians (Athens, GA: Univ. of Georgia Press, 2000); Philip D. Morgan, Slave Counterpoint: Black Culture in the Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake and Lowcountry (Chapel Hill: Published for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg, Virginia, by the University of North Carolina Press, 1998).

5 Examples include Daniel M. Bluestone, Buildings, Landscapes, and Memory: Case Studies in Historic Preservation, 1st ed. (New York: W.W. Norton & Co, 2011); K. Edward Lay, The Architecture of Jefferson Country: Charlottesville and Albemarle County, Virginia (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000)

6 Examples include Noel Ignatiev, How the Irish Became White, Routledge Classics (New York: Routledge, 2009); Claire Jean Kim, Asian Americans in an Anti-Black World (Cambridge, United Kingdom; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2023); Nell Irvin Painter, The History of White People (New York: W.W. Norton, 2011).

7 This work expands on frameworks from Karen Cardozo and Banu Subramaniam, ‘Assembling Asian/American naturecultures: Orientalism and invited invasions’, Journal of Asian American Studies 16 (1) (2013): 1–23.

8 Timothy J. LeCain, The Matter of History: How Things Create the Past, Studies in Environment and History (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2017), p. 216.

9 Shichiro Matsui, ‘The history of the silk industry in the United States: Chapters I and II’, Silk, Oct. 1927: 70–72.

10 Cedric J. Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (Chapel Hill, N.C: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), p. 10.

11 Brian Williams and Jayson Maurice Porter, ‘Cotton, whiteness, and other poisons’, Environmental Humanities 14 (3) (2022): 499–521, at 502.

12 Robinson, Black Marxism, p. 21.

13 Ibid., p. 19.

14 Shichiro Matsui, ‘The history of the silk industry in the United States: Chapter III’ Silk, Nov. 1927: 66.

15 Allison Margaret Bigelow, ‘Colonial industry and the language of Empire; Silkworks in the Virginia Colony, 1607–1655’, in Joseph War (ed.), European Empires in the American South: Colonial and Environmental Encounters, Chancellor Porter L. Fortune Symposium in Southern History Series (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2017), p. 22.

16 With the influx of Spanish precious metals from the Americas in the 17th century, and the attendant monetisation of the European economy, England was scrambling for fungible and transportable commodities to supplement tobacco. Jason Moore, ‘“The modern world-system” as environmental history? Ecology and the rise of capitalism’, Theory and Society 32 (3) (2003): 307–77.

17 At least to my knowledge.

18 The family later anglicised the name, so by living memory, went by Durie. I am unsure of when this transition happened, and will use both Durie and Durier depending on the timeframe of the documentation/conversation, but both are effectively the same surname.

19 Owen Stanwood, The Global Refuge: Huguenots in an Age of Empire (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), p. 4.

20 Robinson, Black Marxism, pp. 21–24.

21 Stanwood, The Global Refuge, p. 9.

22 While it is unclear from the records I have found to date the specifics of the terms and appeals used to obtain Durier’s passage to the US and the group of Frenchmen’s 1686 land patent, I am connecting the broader strokes of the use of Huguenot identity in Huguenot-British relations to wider trends and administrative control of New Jersey via the British proprietorships that would have had the power to grant land to settlers like Durier. Joseph R Klett, ‘Using the Records of the East and West Jersey Proprietors’ (New Jersey State Archives, 2014).

23 Stanwood, The Global Refuge, pp. 84–85

24 Ibid, The Global Refuge, p. 4.

25 For a more detailed explanation of shifts in practices and crop combinations in the Virginia Chesapeake and Piedmont during this time period, see Philip D Curtin, Grace Somers Brush and George Wescott Fisher, Discovering the Chesapeake: The History of an Ecosystem (Baltimore, Md: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001); Morgan, Slave Counterpoint: Black Culture in the Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake and Lowcountry.

26 Carolyn A. Copenheaver et al., ‘Non-native plants observed in North America by 18 th century naturalists’, Écoscience 30 (1) (2023): 39–51, 46-47.

27 Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006).

28 Marsh here is speaking about the Carolina colony, but the same could be said of silk culture more broadly across the historiography of the US. Ben Marsh, ‘Silk Hopes in Colonial South Carolina’, Journal of Southern History 78 (4) (2012): 807–54, at 808.

29 In Virginia, local organisations like Albemarle County’s Hole & Corner Club proliferated and, by the 1850s, these groups organised into a State level agricultural society. Charles W. Turner, Virginia’s Green Revolution (Wayneboro: The Humphries Press, Inc, 1986).

30 The Southern Planter of Richmond is one of the perodicals published regularly in closest proximity to Charlottesville. The editor in the mid 19th Century, Frank G. Ruffin, was born near Charlottesville and returned to the area in the 1840s. Richmond is about 70 miles from Charlottesville/Albemarle County but well connected by waterways and roads, and later railroads and highways.

31 Alexander G. Weheliye, Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014).

32 Italicised emphasis in original, bold emphasis by author. ‘Another enemy to the wheat crop’, The Southern Planter, Aug. 1853.

33 ‘A most extraordinary cure effected by M’LANE’S CELEBRATED VERMIFUGE’, Boston Pilot, 25 Aug. 1855.

34 Emphasis added by author. G.F.H, ‘Lime’, The Southern Planter, Aug. 1853, 243.

35 Emphasis added by author. ‘Red-Winged blackbird’, The Southern Planter, Sept. 1853: 281–82.

36 Edmund Ruffin and Willoughby Newton, ‘Supplement to the Southern Planter’, The Southern Planter, Supplement to the Southern Planter (Dec. 1853): 1–16, 12–13.

37 Nell Irvin Painter locates what she calls the ‘first enlargement of American whiteness’ in the early 19th century, when non-property holding white men were granted the right to vote. Ruffin’s direct engagement with the potential white working class indicates that he does to some extent need to appeal to a wider audience who was not slave-owning. Painter, The History of White People.

38 The same issues of Southern Planter that outlined agricultural practices of planters also had repeating advertisements for booksellers in Richmond who sold tomes by American landscape gardeners like A.J. Downing and others. One example: ‘To agriculturalists’, The Southern Planter, Jan. 1853.

39 Peter Del Tredici, ‘The introduction of Japanese plants into North America’, The Botanical Review 83 (3) (Sept. 2017): 215–52, at 216.

40 Peter Hatch, The Gardens of Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello (Charlottesville, VA: The Thomas Jefferson Foundation, 2001).

41 Del Tredici, ‘The introduction of Japanese plants’, 216.

42 Matsui, ‘The history of the silk Industry in the United States: Chapter III’, 71.

43 Ibid., p. 71.

44 Virginia Historic Landmark Commission Staff, ‘National Register of Historic Places Inventory- Nomination Form: Morea’ (United States Department of Interior-National Park Service, 1983).

45 Thomas Addis Emmet, A Memoir of John Patten Emmet, M.D: Formerly Professor of Chemistry and Materia Medica in the University of Virginia : With a Brief Outline of the Emmet Family History (New York: Privately Printed, 1898), p. 40.

46 Melvin Urofski, ‘Sale of Monticello | Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello’, T.H. Jefferson Research and Education: Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia, 2001: https://www.monticello.org/research-education/thomas-jefferson-encyclopedia/sale-monticello/.

47 Robinson, Black Marxism, pp. 36–38.

48 Noel Ignatiev, How the Irish Became White (New York: Routledge, 2009), p. 70.

49 Gayle M. Schulman, ‘Slaves at the University of Virginia’, Unpublished (African American Genealogy Group of Charlottesville/Albemarle, May 2003).

50 Thomas Jefferson appointed him to the faculty in 1825.

51 Ignatiev, How the Irish Became White, p. 81.

52 Matsui, ‘The history of the silk industry in the United States: Chapter III’, 67–77.

53 ‘The Life of Jokichi Ujie, A Big Landowner’ (Kakuda Homeland History Museum, unknown date).

54 Between the 1630s and 1854, the shogunate in Japan had ruled over a ‘sasoku’ or closed country policy to allow it to monopolise trade with the Chinese and Dutch. Yasuhiro Makimura, Yokohama and the Silk Trade: How Eastern Japan Became the Primary Economic Region of Japan, 1843–1893 (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2017), p. xv.

55 Unknown, ‘The Life of Jokichi U---’.

56 The pebrine outbreak crippled the French and Italian sericultural regions by 1865. Fernando E. Vega, Harry K. Kaya and Yoshinori Tanada, Insect Pathology, 2nd ed. (Amsterdam: Elsevier/Academic Press, 2012).

57 Giovanni Federico, An Economic History of the Silk Industry, 1830–1930 (Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997), p. 36.

58 Ibid, p. 38.

59 Lisa A. Onaga, ‘Bombyx and bugs in Meiji Japan: Toward a multispecies history?’ Scholar & Feminist Online 11 (3) (2013).

60 Matsui describes the burning of 450,000 egg cards that failed to export to France at Yokohama harbour that year, amounting to a loss of over 85,000 Yen. Matsui, ‘The history of the silk industry in the United States: Chapters I and II’, p. 74.

61 Ibid., 75.

62 Makimura, Yokohama and the Silk Trade, p. xiii.

63 Shichiro Matsui, ‘The history of the silk industry in the United States: Chapter IV’, Silk, Dec. 1927: 73–44.

64 Ibid.

65 Matsui notes that by the 1920s, Virginia was only the 7th state in the nation in terms of silk production, and that the industry was mostly still centred in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Ibid, 77.

66 D. Edwan, ‘Armstrong Knitting Factory VDHR Property Survey Form VDHR File 104-0242’ (Virginia Department of Historical Resources, n.d.).

67 Dan Heuchert, ‘Bankrupt local firms provide gold mine for social, labor historians’, Inside UVA, 28 Jan. 2000.

68 Michael A. Godfrey, Field Guide to the Piedmont: The Natural Habitats of America’s Most Lived-in Region, from New York City to Montgomery, Alabama (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2012).

69 Examples include William A. Lankford who bought 30 acres of land adjacent to what would eventually become the IX silk complex in the 1920s. Between 1902 and his death in 1922, he ‘developed one of the best known and largest wholesale green house and growing enterprises in the state. Besides catering to a large and increasing patronage in cut flowers and pot plants, he specialized in raising irises, peonies, and gladioli for the southern and northern wholesale markets, many acres being devoted to the culture of these plants.’ ‘William A. Lankford’, The American Florist, 4 Feb. 1922. Valley View Nursery also operated in the northern portion of town in the 1930s, and pages from its catalogue are shown in the figure.

70 Lyman Carrier, ‘The United States Agricultural Society, 1852–1860: Its relation to the origin of the United States Department of Agriculture and the Land Grant Colleges’, Agricultural History 11 (4) (1937): 278–88.

71 An early example of such a southern player was William B. Allwood, who directed the agricultural experiment station in Virginia in 1888, and was a horticulturalist and entomologist. He wrote numerous articles in Richmond’s Southern Planter about methods for applying insecticides and fungicides and ways of controlling fungal diseases through the extermination zones for host trees, and advised decisionmakers on state and federal level legislation to establish quarantines and elimination regimes for new crop-threatening creatures as they emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His close working relationships with officials at the USDA would have been both a conduit for Virginian ideas to permeate the broader discussion of national policy, and a path for West Coast anti-Asian pest ideologies described by Shinuzoka to be transmitted to Virginia. Curtis W. Roane, ‘A history of plant pathology in Virginia (1888–1897)’, University Archives of Virginia Tech, 23 Sept. 2004: https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/1a880b72-b0f0-4c14-ade5-ac9455350c4f/content.

72 Jeannie Natsuko Shinozuka, Biotic Borders: Transpacific Plant and Insect Migration and the Rise of Anti-Asian Racism in America, 1890–1950 (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2022).

73 Shinozuka explains the contention over the San Jose scale in the 1890s as an example – scientists quarreled over whether the pest originated in the US, in China or Japan, but the racialisation of the pest as Asian persisted in discourse, despite the indeterminate origins of the creature. Ibid.

74 Ibid., p. 20.

75 Major federal laws included the 1905 Insect Pest Act, Plant Quarantine of 1912, the Plant Quarantine 37 (PQN37) of 1919. In Virginia, major early state laws were the 1899 Crop Pest Law and an 1896 law to address the fact that the ‘fruit industry in Virginia is threatened with serious and irreparable damage by an insect known as the San Jose, or pernicious scale’. Wm. B Alwood, ‘Legislation for the suppression of the San Jose Scale in Virginia’, Southern Planter 59 (5) (1888): 238–240, at 238.

76 Major federal laws included the 1875 Page Act, the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, the Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907, the Asiatic Barred Zone/Immigration Act of 1917, and the 1924 National Origins Act.

77 Painter, The History of White People.

78 Howard Ira Durie, The Durie Family (Pomona, NY: Howard Ira Durie, 1985), pp. 185, 233.

79 My great Aunt Pat insists they ‘made a claim in the Oklahoma Land Rush, though they were not ‘Sooners’. Pat Durie, ‘Dear Debbie’, 12 June 2007..

80 Theodore Allen, The Invention of the White Race, Second edition (London ; New York: Verso, 2012), p. 120–121.

81 Colin Woodard, American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America, A Penguin Book History (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2012), p. 102.

82 Michael Omi and Howard Winant, Racial Formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s, 2nd ed (New York: Routledge, 1994).

83 Francesca Morgan, A Nation of Descendants: Politics and the Practice of Genealogy in U.S. History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2021), p. 41.

84 ‘The Huguenot Society of America’, 2023: https://www.huguenotsocietyofamerica.org/.

85 ‘About – The Holland Society of New York’, https://hollandsociety.org/about/ (accessed 10 Jan. 2024). The Durie surname is one of many that can be used to gain membership to the society.

86 ‘1889 – The Scotch-Irish Society of America’, Discover Ulster Scots, https://discoverulsterscots.com/emigration-influence/america/scotch-irish-america-timeline/1889-scotch-irish-society-america ‘(accessed 17 Jan. 2024).’.

87 Examples include in Virginia, H.H Trout, ‘The “Scotch-Irish” of the Valley of Virginia, and their influence on medical progress in America’, Annals of Medical History 10 (1) (1938): 71–82. And, in my family, the Durie name and 17th century homestead in New Jersey appear in a tome on colonial Dutch homes, a book with an introduction by then President, Franklin Delano Roosevelt: Rosalie Fellows Bailey, Pre-Revolutionary Dutch Houses and Families in Northern New Jersey and Southern New York (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1936).

88 Jean Maria O’Brien, Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians out of Existence in New England, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010).

89 Gale E. Peterson, ‘The discovery and development of 2,4-D’, Agricultural History 41 (3) (1967): 243–54, at 247.

90 Ibid., 248–51.

91 Ibid., 252.

92 F.L. Timmons, ‘A history of weed control in the United States and Canada’ Weed Science 53 (6) (2005): 748–61, at 755.

93 Ibid., p. 748.

94 Peterson, ‘The discovery and development of 2,4-D’, 252.

95 Ibid., 249.

96 Examples include ‘Kill poison ivy’, The Bee, 13 July 1945; ‘Orr Seed Co.’, Norfolk Ledger-Dispatch, 18 May 1945; ‘Tait’s Thorobred Seeds’, Norfolk-Ledger Dispatch, 17 May 1945; Peterson, ‘The discovery and development of 2,4-D’; ‘We now have Weedone’, Waynesboro News-Virginia, 13 July 1945.

97 Shinozuka notes the proliferation of Japanese beetle killer advertisements on the East Coast in the run-up to World War II, but these advertisements lived on in Virginia into at least the 1950s. Shinozuka, Biotic Borders, pp. 154–55.

98 Timmons notes that by 1969, 120 herbicides were available for public use, and, by 1967, sales of herbicides reached 348 million pounds. Timmons, ‘A history of weed control in the United States and Canada’, p. 752.

99 One example of such language: ‘most weeds presently in the United States and causing losses to American agriculture were originally of foreign origin’. J. Phil. Campbell, Acting Secretary of Department of Agriculture to Roy L. Ash, Director of Office of Management and Budget, 26 Dec. 1974, White House Records office, Legislation Case files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library: https://www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov/library/document/0055/1668939.pdf

100 Elton’s work is often noted as a first and influential tome on foreign plants as ecological threat. Charles S. Elton, The Ecology of Invasions by Animals and Plants. (London: Methuen, 1958).

101 William Jefferson Clinton, ‘Executive Order 13122 of February 3, 1999, Invasive Species’, Federal Register 64 (25) (8 Feb. 1999): 6183–87, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-1999-02-08/pdf/99-3184.pdf. This order was further strengthened by a later amendment to order in 2016: Barack Hussein Obama, ‘Executive Order – Safeguarding the Nation from the Impacts of Invasive Species’ (The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, 5 Dec. 2016), https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2016/12/05/executive-order-safeguarding-nation-impacts-invasive-species

102 An Act to require the Secretary of Agriculture to establish a program to provide assistance to eligible weed management entities to control or eradicate noxious weeds on public and private land, Public Law 108-412 (30 Oct. 2004): 2320–2324.