Sessile – a term used in biology to describe an animal’s inability to locomote – could also describe the situatedness of trees. In a typical day, when we move around the world on foot or wheels, the trees we pass remain in place. Now consider that a 24-hour period is an expression of human time, an anthropocentric vantage point. Trees, we breathe invited visitors to New York’s Wave Hill into reflections that depart from familiar timeframes and tree forms. Alternatively, the works on view in the exhibition zoomed in and out of tree mysteries and matter. The show explored an ecology that emphasises a symbiotic relationship between humans and trees, giving equal weight to what is known and what awaits discovery. The passionate inquiry of fifteen contemporary artists working across diverse media and methods invited visitors into worlds of abstraction, intuition and open-ended curiosity. The exhibition was articulated by jagged driftwood, billowing fabric, delicate linework, surgical clamps, electroformed copper, latex vines, organic remnants, moving pictures, disappearing sounds, and juxtapositions of floral, faunal and fungal bodies, making the formal experience of the show rich and sometimes daunting.

Sessile – a term used in biology to describe an animal’s inability to locomote – could also describe the situatedness of trees. In a typical day, when we move around the world on foot or wheels, the trees we pass remain in place. Now consider that a 24-hour period is an expression of human time, an anthropocentric vantage point. Trees, we breathe invited visitors to New York’s Wave Hill into reflections that depart from familiar timeframes and tree forms. Alternatively, the works on view in the exhibition zoomed in and out of tree mysteries and matter. The show explored an ecology that emphasises a symbiotic relationship between humans and trees, giving equal weight to what is known and what awaits discovery. The passionate inquiry of fifteen contemporary artists working across diverse media and methods invited visitors into worlds of abstraction, intuition and open-ended curiosity. The exhibition was articulated by jagged driftwood, billowing fabric, delicate linework, surgical clamps, electroformed copper, latex vines, organic remnants, moving pictures, disappearing sounds, and juxtapositions of floral, faunal and fungal bodies, making the formal experience of the show rich and sometimes daunting.

The magnetism of trees is what held the disparate artistic journeys of the exhibition together. Undeniably, the leafy giants had us under their spell, having successfully lured artists – and now us gallery visitors – into their kingdoms. We humans are not central to their worlds – we are their subjects among the flora, fauna and funga that find home, food and breath in the trees – and we are only a part of an interdependent, interspecies web.

The research of Abigail Culpepper, a doctoral candidate at Brown University, focusing on problems of ecocritical reading and questions of literary scale, can aptly be invoked here.1 Her theory of textual sessility provides a gorgeous framing for taking in the full spectrum view of Trees, we breathe, when the sessility of a tree, like that of a text – and in this writing, an artwork – provides a portal into a dynamic world of interconnectivity. Culpepper speaks to a sessility that cultivates multiscalar perspectives, one that reveals inherent activity. Consider the activity that becomes visible when examining plant matter under a microscope, or the seasonal movement of tree sap up and down a maple tree trunk, or the cumulative impact of lichen that, over centuries, can transform rock into soil.

The artists of Trees, we breathe observe vibrant activity through practices of being with trees – spending slowed-down time with them and viewing them from unfamiliar vantage points. Each artwork is a multisensory conversation. The Glyndor Gallery showcased most of the work, and larger installations were woven into the surrounding Wave Hill landscape. While artists contemplate tensions between humans and the more-than-human world, Wave Hill celebrated its sixtieth anniversary as a public garden and cultural institution, openly wrestling with its occupation of Indigenous land. Within the institution’s commitment to multiple levels of questioning, there rests a patience, an active sitting with unsettling ideas. The generosity of Trees, we breathe was the space it created for visitors to be still with layered entanglements which expand far beyond the 28 acres of Wave Hill and into the choices and assumptions we make in our daily lives about how we live in and with the natural world.

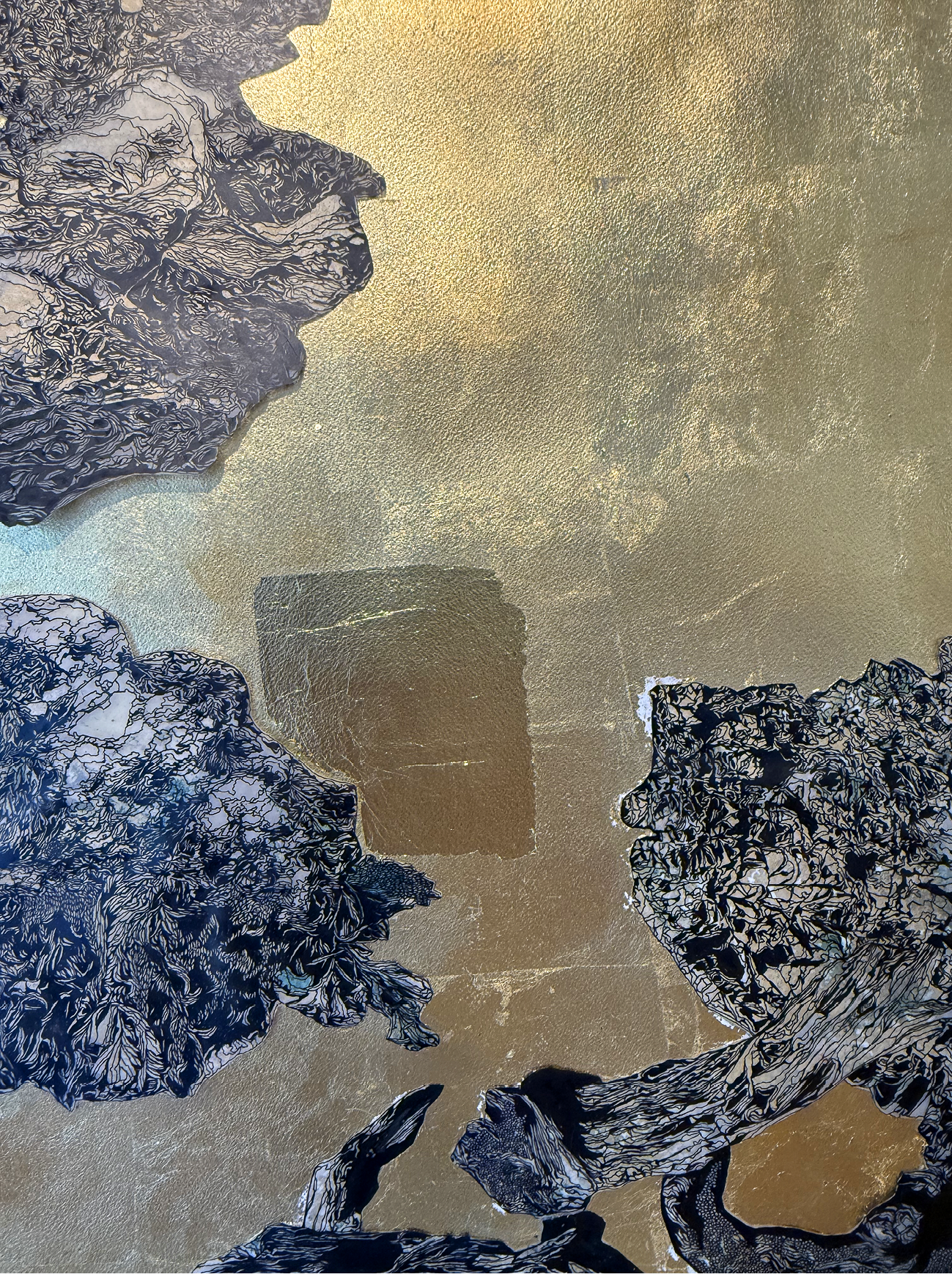

Sarah Ahmad’s drawings Fractured Cosmos IV (2017–2025) and Fractured Alchemy (2024) grounded the gallery exhibition with works that evolved from her intermittent drawing practice over nearly a decade. Her works, created with black ink on vellum, include gold leaf – a nod to the alchemists and the non-linear transformations that are mapped, charted, and explored within these dynamic works. Ahmad achieves rich depths, textures and lines that are comforting despite the challenging terrain they document and reveal. Ahmad’s patient and rigorous artistic process enables her to present intricate complexity with remarkable beauty and clarity – the time she invests in the work becomes a gift to the viewer. To follow the lines of these works is to have your consciousness woven into Ahmad’s communing with trees.

Figure 1.

Sarah Ahmad, Fractured Cosmos IV, 2017–25; Sari Carel, City of Trees, 2021–ongoing; on view in Trees, we breathe at Wave Hill, 2025. All works courtesy of the artists.

Photo: Stefan Hagen. Courtesy of Wave Hill.

Figure 2.

Sarah Ahmad, Fractured Alchemy (detail), 2024.

Photo: Jennifer L. Karson.

Julia Oldham’s video Dendrostalkers (2022) transported gallery visitors into a speculative future. Combining actual footage of clear-cut Oregon forests and delightfully simple hand-drawn animations, Oldham worked with tropes from reality TV, online forums, and supernatural horror. The work introduces Dendrotropes, trees that have evolved to protect themselves from the consequences of clear-cutting forest practices. Not only can they escape to an unknown dimension, but they can also take humans with them! What is this alternative refuge and how do the Dendrotropes transport themselves there? How do they treat the people they bring there? What can be done in 2025 to make sure that if such a future comes to be, the Dendrotropes will be friendly to humans? The playful provocations of Dendrostalkers shatter Western paradigms of human-tree relationships, challenging us to confront trees as superior beings.

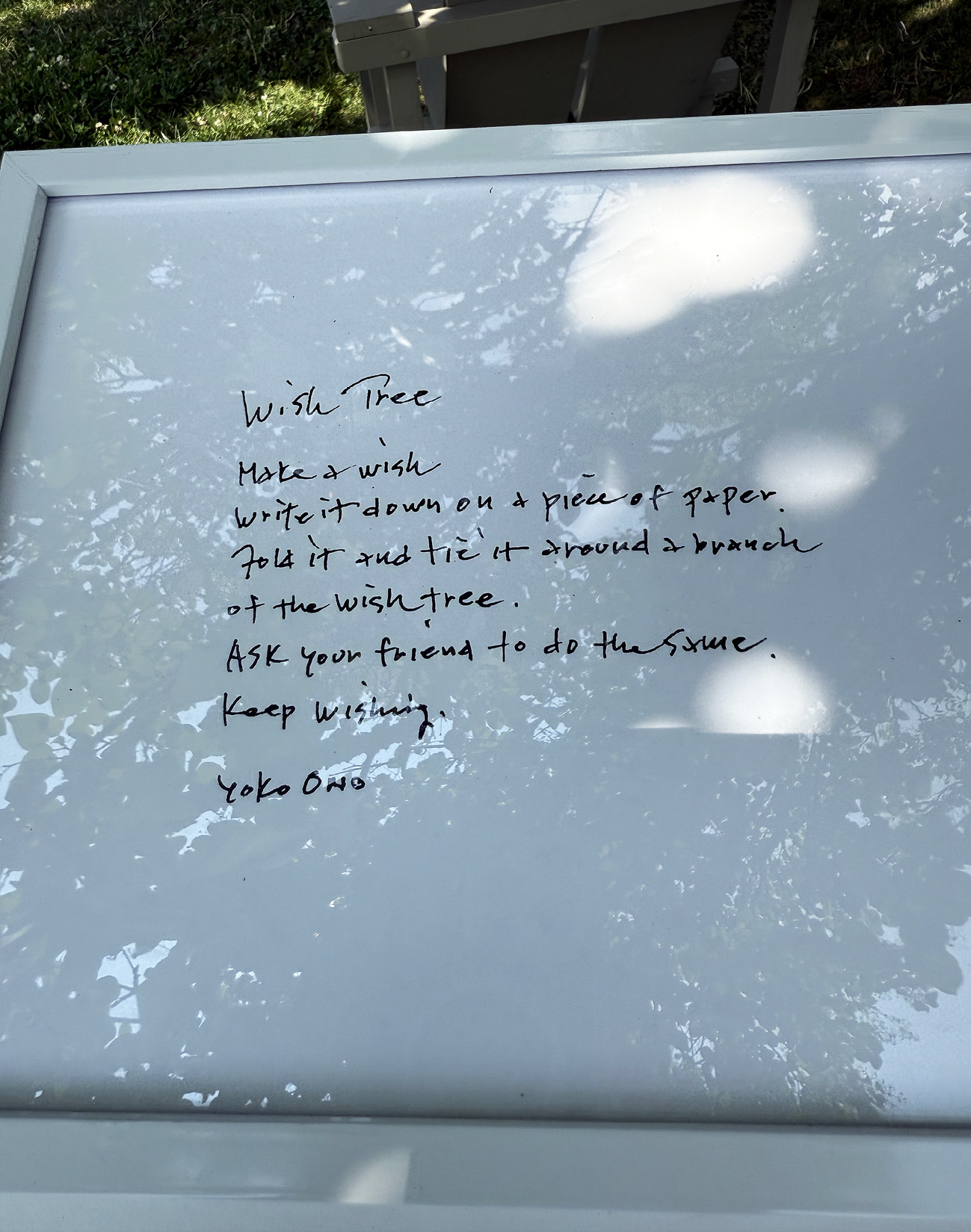

Trees, we breathe, continued imaginative play with its outdoor installation of Yoko Ono’s Wish Tree (1996/2025). Inspired by her childhood visits to Shinto shrines in Japan, Wish Tree invited visitors to write down a wish on a white card, likened by Ono to a white flower blossom, and then attach the card with a string to a branch on a pair of Wave Hill’s tree lilacs. How might the experiences of the human-tree relationships featured in Trees, we breathe have influenced visitors’ wishes? In contrast to the speculative narrative of Dendrostalkers, most of the wishes that adorned Wish Tree were down-to-earth: intimate wishes for the health and wellbeing of family, global wishes for harmony between peoples and the natural world, and desires for more interspecies connections. At the time of writing, Wave Hill had collected over 3,000 wishes, including a wish to have a pet dog, to become a mermaid, and for plants that can talk. During the exhibition, the tree lilacs appeared as guardians to the earthly wishes from visitors, their leaves rustling with the wishes on paper. Eventually, all the wishes would be collected and placed within Ono’s IMAGINE PEACE TOWER, from 2007, a monument and world beacon for peace located on Viðey Island in Reykjavik, Iceland. Lit at special times during the year, the landmark sends a penetrating ray of light into the night sky, symbolically releasing the wishes that fill its tower, beaming them out into an expanding universe of possibilities.

Figure 3.

Yoko Ono, Wish Tree, 1996/2025, on view in Trees, we breathe at Wave Hill, 2025. Artwork © Yoko Ono.

Photo: Jennifer L. Karson.

Trees, we breathe was organised by Gabriel de Guzman, Director of Arts and Chief Curator; Rachel Raphaela Gugelberger, Curator of Visual Arts; and Afriti Bankwalla, Curatorial Administrative Assistant. A digital version of the exhibition catalogue can be downloaded from Wave Hill’s website. (https://www.wavehill.org/uploads/programs/WH-25-TREES-cat-REPRINT_FINAL.pdf) The exhibition featured work by Sarah Ahmad, Andrea Bowers, Sari Carel, Michelle Frick, Ben Gould, Sara Jimenez, Weihui Lu, Julia Oldham, Yoko Ono, Yeseul Song and Jesse Simpson, Rose B. Simpson, Rachel Sussman, Carlie Trosclair and Sam Van Aken.

Figure 4.

Yoko Ono, Wish Tree, 1996/2025, on view in Trees, we breathe at Wave Hill, 2025. Artwork © Yoko Ono.

Video still: Jennifer L. Karson.

For full video, click on the image

or see

https://vimeo.com/1152296815

Jennifer L. Karson is a senior lecturer in the School of the Arts at the University of Vermont and the keeper of the Damaged Leaf Herbarium and Dataset.

Email: Jennifer.Karson@uvm.edu

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-7684-4617

1 Abigail Culpepper, ‘How Are We Still Reading? Towards a Theory of Textual Sessility’, paper presented at the Thinking with Plants and Fungi Conference, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, 17 May 2025.