Heather Craddock

The Absence of the Ackee Tree: Jamaican Botanical Resistance and Kew’s Colonial Archive

ABSTRACT

On a monument to the people enslaved on the grounds of the University of the West Indies campus in Kingston, Jamaica, groves of ackee trees are acknowledged as ‘botanical markers’ of former slave villages. This use of the ackee as a long-term memorial of enslavement exemplifies the role of trees as sites of cultural memory and demonstrates how ackee became the principal botanical symbol of Jamaican identity. However, there is scarcely any material about ackee in the archives of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, particularly in the Miscellaneous Reports, a collection of archival material about economic botany in the British empire. This article argues that this absence is the result of ackee’s long association with resistance to colonial exploitation, as a tree bearing a potentially poisonous fruit, growing beyond the colonial spaces of the plantation and botanical garden.

Keywords

Jamaica, botanic gardens, colonial botany, ackee

Concealed within the fleshy yellow pouches which were edible was a sprinkling of red powder – ‘deadly poison.’ … Jamaicans were the only island people daring enough to eat the ackee.

Concealed within the fleshy yellow pouches which were edible was a sprinkling of red powder – ‘deadly poison.’ … Jamaicans were the only island people daring enough to eat the ackee.

Michelle Cliff, Abeng (1984)

[Note: Given the colonial context of many of Kew’s archival records, there are examples of offensive language in this article.]

The University of the West Indies campus at Mona in Kingston, Jamaica, hosts monuments to the people enslaved on the Mona Estate. Based on evidence in survey maps and botanical and agricultural reference points, the monuments identify the areas where enslaved people lived which are now part of the university grounds and mark these otherwise invisible histories. A monument close to the entrance to the university, titled ‘Mona Village’ notes that the ‘groves of ackee trees which have long flourished in the area are an accepted botanical marker of a slave village.’1 (Figure 1) This use of the ackee tree as a long-term memorial of the legacy of enslavement in a specific area exemplifies the role of plants as sites of cultural memory, and offers an example of how ackee attained its primacy amongst botanical symbols of Jamaican identity.

Ackee is now the national fruit of Jamaica and its dominance amongst Jamaican foods is evident in its selection as the cover image on Barry Higman’s seminal work on the culinary uses of plants and animals on the island, Jamaican Food (2008), and frequent appearance in literature about Jamaica. However, few pages are devoted to the fruit in the Miscellaneous Reports, an archival collection focused on economic botany across the British empire from around 1850 to 1928, held at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. These archival records are made up of administrative and scientific reports, along with correspondence, newspaper cuttings, photographs, illustrations, plant specimens and maps. They include volumes focused on the activities of the Jamaican Botanical Department, which formed a hub of botanical activity in the Caribbean as part of Kew’s network of colonial botanic gardens.

At Mona, the memorial situates the ackee trees in close proximity to the botanical gardens at Hope, built on the former site of the neighbouring Hope Plantation. At Kew, the Jamaican volumes in the Miscellaneous Reports include only three items in the section entitled ‘Akees’: a cutting from the 19 February 1892 edition of the Jamaica Post entitled ‘Akees as Food’ by J.J. Bowrey; a section from the 15 December 1900 edition of the Pharmaceutical Journal, with an article entitled ‘Notes on the Oil of Akee’ by E.M. Holmes, alongside the article ‘The Character of Oil of Akee’ by W. Garsed; and a printed pamphlet by Holmes and Garsed containing the same information.2 There is little consideration of ackee’s popularity as an edible plant; nor of its cultivation in the botanical gardens of Jamaica; and only brief mentions of its introduction to the island, its minor presence in some of the gardens, and its sale as a timber or shade tree.

Ackee’s popularity as a food is largely limited to Jamaica and to Jamaican diasporic communities; elsewhere in the Caribbean it has faced consistent rejection due to fears about its toxicity. Ackee’s central role in the botanical landscape of Jamaica should clearly be addressed, yet there have been few studies of its cultural history.3 This is surprising considering the direct role ackee plays in preserving the cultural memory and geographies of enslavement. A tree which, from its arrival in Jamaica, was closely associated with enslavement and the botanical agency of the marginalised, ackee has developed into a captivating Jamaican cultural symbol which has become pervasive in literature and travel writing about the island, yet remains underdiscussed in Kew’s archival records. The central question here is why the discussion of ackee is so limited in the Miscellaneous Reports.

In this article I will seek to elicit a narrative from the scarce and disparate materials about ackee in the Miscellaneous Reports. By ‘dwelling on the fragmentary’, as Marisa Fuentes suggests – being attentive to the hints towards repressed voices and attitudes that can be found through the absences and oversights in the collection – I argue that this scarcity of sources is itself evidence of ackee’s role as a food plant of resistance.4 Beginning with the ambiguous origins of ackee in Jamaica and its role in the agency of enslaved people, I will then move to discuss ackee as a food associated with resistance against colonialism, before considering its toxicity and the impact this had on its reception in the nineteenth century. Moving beyond the Kew archive, the remainder of the article will examine the various symbolic resonances ackee acquired in Jamaican culture on its journey towards becoming the national fruit of the island.

This article situates the story of the ackee tree within the large body of work on silences in colonial archives. Much of this work addresses the difficulty of uncovering the experiences and practices of enslaved people in archives. A central question is whether it is ‘possible to exceed or negotiate the constitutive limits of the archive’ in this context, as Saidiya Hartman suggests.5 Stephanie Smallwood responds to this prompt with a call ‘to tell the history that is accountable to the enslaved—the counter-history the archive tells only reluctantly’.6 In the context of botanical archives, such silences can be seen in the absence of discussion of plants associated with marginalised, and particularly, enslaved people. Discussing the significance of oral transfer of botanical knowledge in Jamaica, Miles Ogborn notes that ‘From the mid-eighteenth century, Africans, Asians and Amerindians were seen less and less as the holders of valuable botanical knowledge.’7 This knowledge, when it reached the archive, often did so without recognition of the people who shared it with colonial scientists and collectors, and without its associated cultural significance. Londa Schiebinger argues for the erasure of such knowledge from the archival record – a practice she terms ‘agnotology’ – sometimes as a deliberate act, and often the result of colonial governmental practices that hinder the travel of this type of knowledge.8

Ackee provides a clear example of this, appearing in Kew’s archive primarily in relation to its toxic scientific properties and the circulation of this information through the colonial administration. The archival focus of this article is on the records relating to ackee held at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, which were produced in a post-slavery context in the late nineteenth century. The Miscellaneous Reports were selected and structured into the current archival collection during the early twentieth century, and these acts of curation therefore reflect the colonial institutional aims and biases of the creators. Since discussion of ackee within the Kew archive is limited, this article also explores the ‘archival’ account of ackee in a broader sense; it incorporates literary accounts, travel writing, visual records and memorials, and other cultural representations of ackee.9

Cultivation in Jamaica

Ackee’s association with resistance is closely connected with the spaces in which it was grown. The inscription on the Mona monument also clarifies that ‘[t]he provision grounds where slaves grew much of their food are generally accepted to have been in the higher slopes of long mountain to the South East’.10 This distinction between the provision ground, the plantation and the gardens of the slave village itself is important in situating ackee in its in its geo-historical space. These descriptions note that ackee trees were not grown in provision grounds, nor were they plantation crops, but instead formed part of the villages of enslaved workers in gardens close to their homes, a point which I will return to. A similar monument on the university grounds titled ‘Papine Village’ likewise acknowledges that ‘botanical markers – primarily nearby groves of ackee and mango trees – corroborate’ the location of the village inhabited by enslaved workers, while the Papine Estate’s “‘Negroe Grounds”, where provisions would have been grown, appear to have been nearby, close to the boundary with Hope Estate, to the North’.11 The Hope Estate, on which the botanic garden stands, bordered the Papine Estate, which in turn bordered the Mona estate, highlighting the proximity of Hope Botanic Garden to the ackee groves in question.

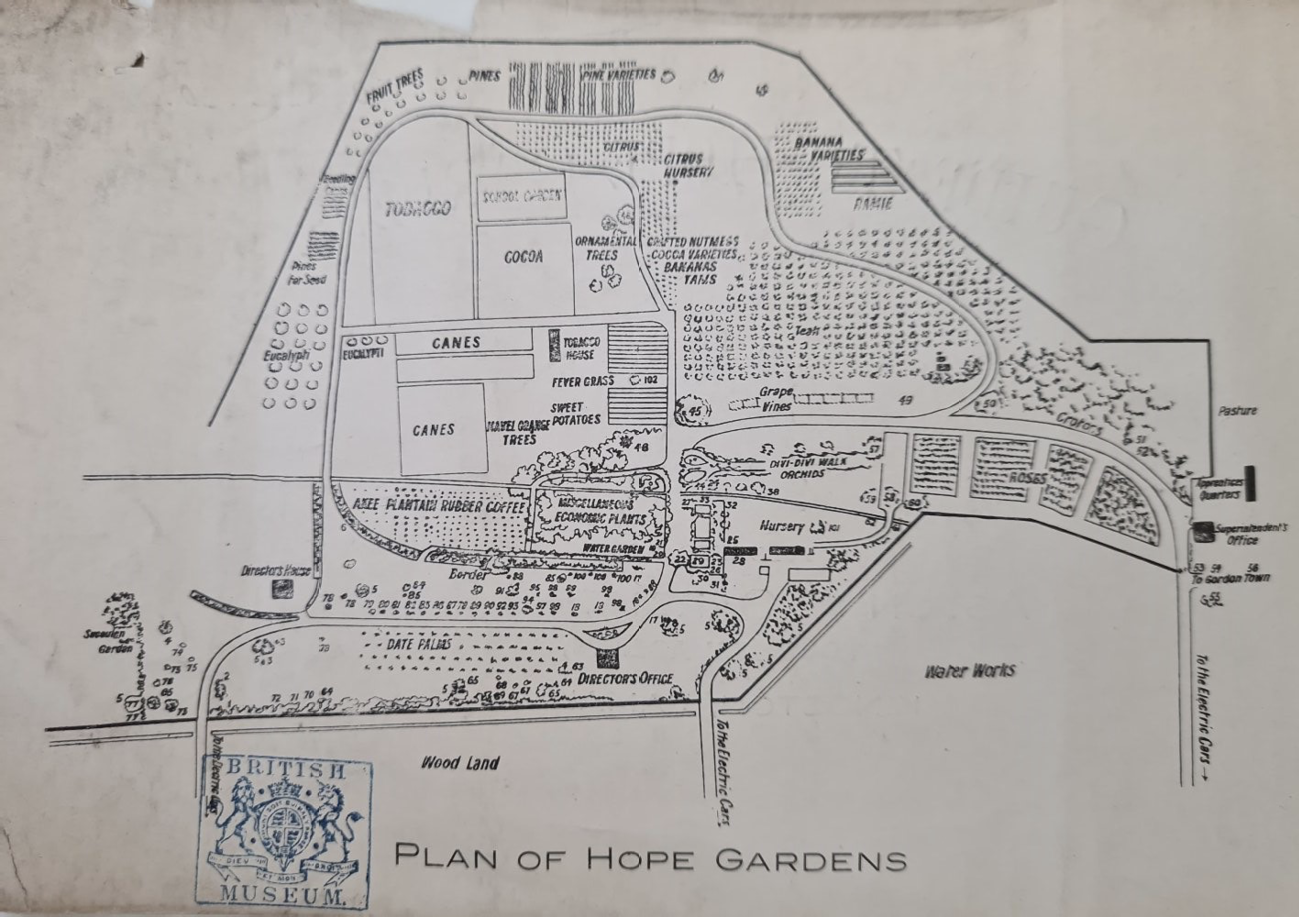

Some of the earliest discussions of ackee in Jamaica are in connection with the botanical gardens in the late eighteenth century, as the article included in the Miscellaneous Reports by E.M. Holmes reveals.12 This article, published in the Pharmaceutical Journal in 1900, indicates that, alongside its primacy as a food plant to the enslaved (and later emancipated) population, Ackee’s medicinal properties were of particular interest to colonial scientists.13 Holmes notes that botanist Arthur Broughton’s Hortus Eastensis (1794) lists ‘Akee’ in a catalogue of plants growing in the botanic garden at Spring Garden near Gordon Town, but it appears to have been cultivated only in the botanic garden as Henry Barham’s Hortus Americanus (1794) does not mention it. Broughton’s catalogue lists the name ‘The Akee’ and suggests the source to be Dr Thomas Clarke, Botanist and Curator of Bath Gardens in Jamaica, in 1778.14 Holmes does not record Thomas Dancer’s 1792 reference to akee, ‘Aka Africana’, in his Catalogue of Plants, which seems to be the first account of its presence in Jamaica, and offers a precise description of its arrival: ‘Another African Fruit, introduced by Negroes in some of Mr. Hibbert’s ships’.15 Writing in 1897, William Fawcett, Director of the Jamaican botanic gardens, confirmed these accounts of ackee’s introduction to the Jamaican botanic gardens in the eighteenth century, adding that it continued to be cultivated in the botanical gardens at Castleton.16 The Guide to Hope Gardens also records the cultivation of ackee at Hope (Figure 2), so there is evidence that ackee was considered valuable enough to have been transferred between botanical gardens in Jamaica.17

The origins of ackee in Jamaica potentially demonstrate the agency of enslaved people in botanical transfers from Africa to the Caribbean. Broughton notes that ‘[t]his Plant was brought here in a Slave Ship from the Coast of Africa, and now grows here very luxuriant, producing every Year large Quantities of fruit; several Gentleman are encouraging the propagation of it.’18 Holmes likewise writes that the ‘ackee tree is a native of the coast of Guinea, in West Africa, not of Jamaica’.19 The scientific name Blighia sapida was given by Kew botanist Charles Konig in 1806 not because Captain William Bligh brought it to Jamaica, but because he brought it to Kew on the Providence in 1793, with the species name sapida referring to the ackee’s savoury taste.20 There is continued uncertainty around the journey of ackee to Jamaica, but it was likely grown for the first time in Jamaica in the 1770s. In his Hortus Jamaicensis (1814), John Lunan also claims that it ‘was brought to Jamaica in a slave ship from the coast of Africa’, and provides the description from Broughton’s Hortus Eastensis, but adds that ‘the delicacy of the white lobes of this fruit when fried or boiled, and eat as marrow, or sweet-breads, or in soups, renders it well worthy of cultivation’.21 The argument for African agency playing a role in intentionally transferring or smuggling seeds is, as Higman argues, ‘plausible and carries more weight in the case of the ackee than it does in the root crops’.22 The ackee tree was a curiosity, of ornamental value, impractical as food for voyagers, and thus unlikely to have been deliberately transferred by slave traders, which sets it apart from other staple crops transferred from Africa.23

The importation by Africans on slave ships of ‘yam, ackee, gourds, and other staples into the Caribbean’ created an ‘alternative economy’ to plantation monoculture.24 These crops were often cultivated in provision grounds, which Judith Carney and Richard Rosomoff describe as ‘botanical gardens of the dispossessed’, arguing that in these spaces ‘Africans realized an alternative botanical vision’ to the plantation.25 As spaces which enabled enslaved people to grow ‘marketable surpluses’ which presented the economic means to resist enslavement, provision grounds held both a practical and symbolic value.26 However, growing in the gardens of slaves and later peasants near their homes, ackee occupied a space outside Sylvia Wynter’s ‘plantation-plot dichotomy’ as the tree was neither grown purely for sustenance (in provision grounds) nor grown only for colonial profit (in plantations).27 There is a sense that ackee inhabits an ambivalent space in terms of its function and value, at once a likely example of African agency and roots in the Caribbean and also a product of chance, a ‘self-propagating’ plant ‘allowed to grow because of the ornamental beauty of the tree’.28 But the absence of ackee in Kew’s Miscellaneous Reports indicates that it did form part of an ‘alternative’ botanical and economic vision. As Sydney Mintz suggests, ackee can be positioned alongside a wider group of plants originating in Africa whose continued cultivation and consumption act as evidence of ‘the will to endure, to resist’ amongst enslaved people.29 Particularly in light of its ornamental value, and limited nutritional value, the cultivation and ongoing popularity of ackee in Jamaica marks a sustained resistance to the set of requirements by which a plant was judged valuable or not by colonial botanists and planters.

Toxicity

The discussion of ackee in the Miscellaneous Reports is entirely in relation to its toxicity. The newspaper article by Government Analytical Chemist, J.J. Bowrey, from an 1892 edition of The Jamaica Post offers a concise summary of the edibility of ackee according to a colonial ‘expert’. Bowrey, who was responsible for experiments relating to food safety, explains that he is writing in response to ‘the late sad deaths on the Long Mountain Road from eating poisonous ackees’ and the fact that ‘many persons are afraid to use this fruit at all, and others are anxious to know how wholesome Akees may be distinguished from dangerous fruit’.30 He proceeds to offer a summary of the dangers of ‘unripe’ and ‘decaying Akees’, but emphasises the ‘wholesome’ nature of ‘fresh ripe Akees … which can be known by its being open, the edible portion firm, and the red part bright in colour’.31 This language of freshness and ripeness is particularly significant in relation to ackee due its poisonous qualities when unripe. It forms part of the distinctive set of terms used to describe ackee which mark its uniqueness in Jamaican botany and culture, as a fruit which requires consumers to understand and respect its threatening potential.32

Fears around the toxicity of ackee have led to interesting methods of sharing knowledge of how to consume it safely across Jamaican culture, as John Rashford emphasises: ‘Tradition says before the fruit is harvested, it must open on the tree naturally, i.e., it must “smile” or “laugh”.’33 Ackee is so closely associated with Jamaican identity that Rashford states that ‘to be Jamaican is to know how to enjoy ackee safely by distinguishing between those that smile and those that do not smile – those that do not smile will kill.’34 The smiling or laughing ackee is anthropomorphised for human safety, just as the seeds of the ackee are compared to eyes, but this image also implies that the fruit is mocking those who fear its toxicity.35 ‘Vomiting sickness’ in Jamaica was first noted in association with ackee around 1880, and this is caused by high levels of hypoglycin A in immature and overripe fruit. This amino acid can damage nerve cells, causing seizures, damage to the liver, severe vomiting and coma, and even death in extreme cases. Concerns around ackee’s poisonous qualities persisted into the twentieth century, and Government bacteriologist and pathologist Henry Harold Scott sought to expand on Bowrey’s earlier studies, producing a series of reports and publications connecting ackee to ‘vomiting sickness’, which received a mixed response from the Jamaican public.36

Consumption of ackee as food and fears about the toxicity of the plant formed part of a wider threat felt by planters that ‘the enslaved would target their masters, other slaves, and animals with painful poisoning administered via food and drink’.37 Though poisonings were not often detected, and shared the symptoms of common diseases of the time, they remained, as Ogborn claims, ‘at the heart of the planters’ botanical fears’, compounded by an awareness of the extensive knowledge of herbal medicines amongst enslaved people.38 This fear was directed particularly towards women, as those preparing food, and practitioners of Obeah – magic and healing traditions in the Caribbean.39 In light of the increasing denigration of spiritual practices associated with poisoning, the difficulty of finding this information in the archival record parallels the absence of ackee from the Miscellaneous Reports later in the nineteenth century.40

The threat of poisoning associated with ackee impacted its reception amongst white colonialists in Jamaica and encouraged the perpetuation of the mystique around it. Holmes’s article offers the anecdotal account of a Mrs J. Seed Roberts ‘who lived for some years in the island’ as the basis for a discussion of the poisonous properties of the ackee fruit, particularly the ‘aril’ or seed covering: ‘in Jamaica the arillus is believed to be poisonous if gathered before the fruit is fully open’.41 Mrs Roberts also provides a basic recipe for ackee ‘either boiled or fried in butter or oil’ and ‘states that the best picture of the plant she has ever seen is in Miss North’s collection at Kew Gardens.’42 Marianne North’s depiction, housed in her own gallery at Kew Gardens, clearly shows the ackee in its ‘open’ state, ready to be picked and consumed, and demonstrates the striking and colourful appearance of the fruit, emphasising its beauty rather than the threat of the plant (Figure 3).43

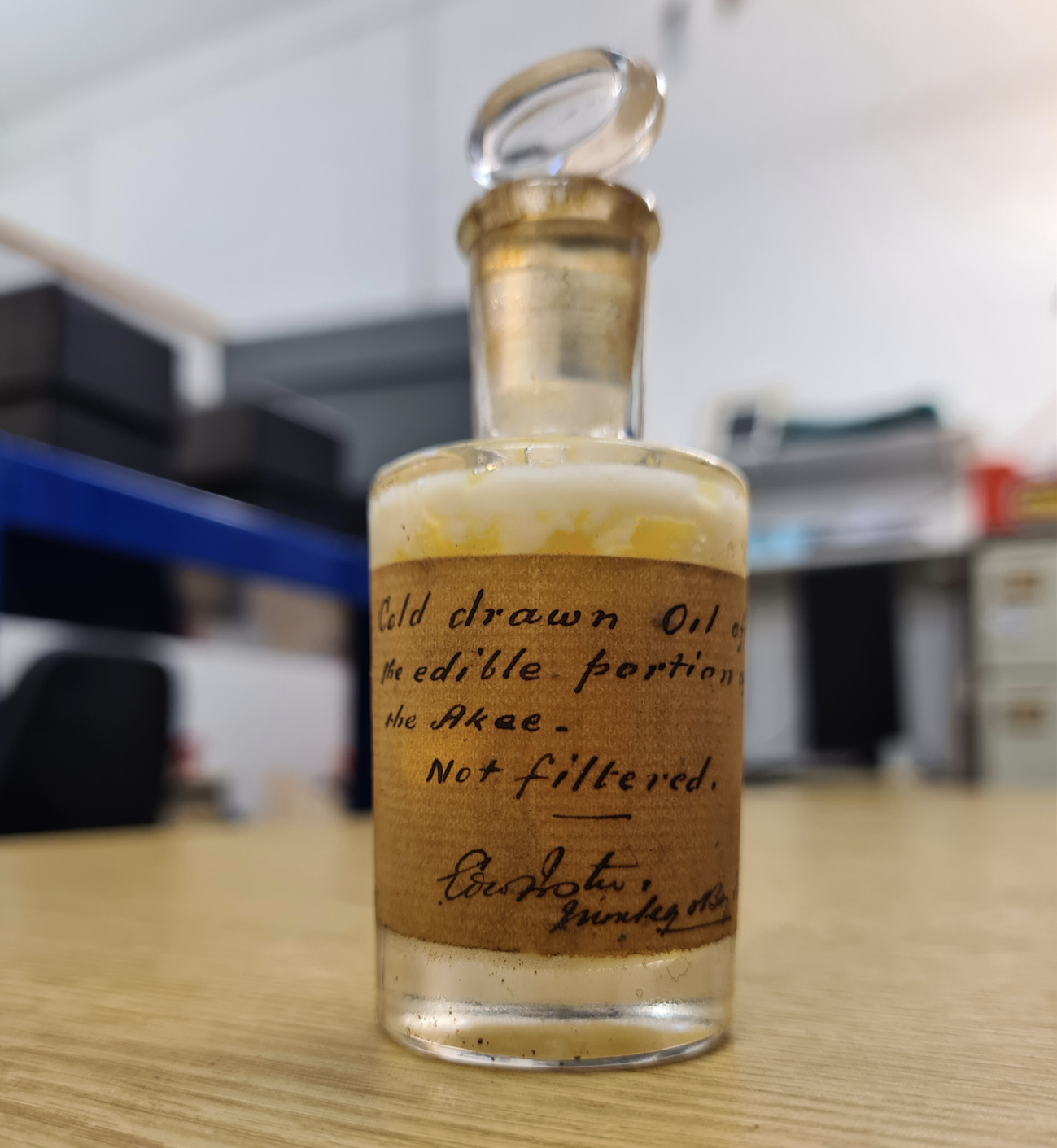

The impact of this reception of ackee amongst colonial travellers and botanists in Jamaica is reflected in the limited attention to the fruit in Kew’s Miscellaneous Reports, but also in other sources displaying the circulation of materials about ackee at Kew. Acknowledging how the information in his article came into his possession, Holmes notes that the specimen in question was ‘handed to the Director of the Botanic Gardens in Jamaica [William Fawcett], who forwarded it to the Museum of the [Pharmaceutical] Society, in the hope that some information concerning its physical properties, and its possible uses in commerce, might be obtained thereby’.44 The specimen is now held in the Economic Botany Collection at Kew, having been passed on from the Museum of the Pharmaceutical Society in 1983, and consists of a glass jar inside which is a small bottle holding the oil of the ackee and labelled ‘Cold pressed drawn oil of the edible portion of the Akee. Not filtered’ (Figure 4).45 The relevant index card confirms that the specimen was presented by Fawcett, Director of Public Gardens and Plantations in Jamaica in 1900. Nonetheless, while the circulation of this specimen marks one attempt to disseminate knowledge about ackee’s medicinal or culinary potential, it does not appear to have been taken any further, as there are few other records about ackee in the Miscellaneous Reports.

Ackee was, however, of interest to botanists, as its inclusion in other Kew correspondence and publications demonstrates, such as the January 1888 Bulletin of the Botanical Department of Jamaica, which lists ackee amongst trees on sale for timber or shade plants.46 Various letters in Kew’s Directors’ Correspondence collection also refer to the transfer of seeds or knowledge about Blighia sapida across different countries, including St Kitts, Brazil, India, the USA and Mexico, revealing that some botanical enterprise was undertaken in relation to the plant. The director of Kew in 1924, Arthur Hill, received a letter from Michael Grabham, a doctor working in Jamaica, enclosing seeds including Blighia sapida, along with local reflections on why ‘the “butter ackee” – is much esteemed’:

During protracted droughts the people on these arid plains are almost entirely dependent on it for food. It is a favourite article of food with the Indian coolies … I have myself eaten the fruit almost daily for 30 years. The tree is cultivated in Costa Rice and Haiti. Why not try and naturalise it in the famine districts of India?47

Grabham’s personal assurances as to the safety of the plant and encouragement of its wider cultivation demonstrate that Kew was aware of ackee’s possibilities as a food plant, but continuing uncertainties around ackee’s safety hindered its development as an economic opportunity.

Ackee in Travel Writing and Literature

Ackee features more frequently elsewhere in writings about Jamaica, particularly in literature and travel writing, in which it develops from the nineteenth century into a prominent cultural symbol in contemporary Jamaica. Ackee was consumed as early as 1811 by the wealthy class of white colonialists during the period of enslavement in Jamaica, as seen in botanist William Jowit Titford’s claim that it ‘tastes just like marrow, and is a delicious vegetable’. Higman also suggests that the dish ackee and saltfish was created by this white planter class because the fried dish required expensive oil or butter and saltfish.48 Importantly, Higman asserts that ‘no explicit reference to enslaved people eating ackee in any form has been found’.49 Yet, as we have seen, ackee trees continue to grow in spaces which were formerly slave villages, so this absence is likely a reflection of the underrepresentation of enslaved people in archival evidence of food consumption. Matthew Gregory Lewis, author of The Monk and wealthy owner of plantations and enslaved people in Westmoreland in Jamaica, gives his impression of ackee in his 1816 account of visiting his property: ‘The achie fruit is a kind of vegetable, which generally is fried in butter. Many people, I am told, are fond of it, but I could find no merit in it.’50 The minimal presence of ackee in the Miscellaneous Reports suggests that this unenthusiastic assessment of the fruit was the one which prevailed among the planter classes throughout the nineteenth century.

Later in the nineteenth century, Reverend Charles Daniel Dance, a British Anglican missionary in Guyana, wrote in 1881 of ackee being ‘generally eaten fried or boiled with saltfish or as a substitute for the egg in egg sauce’, adding that ‘[i]f colonial epicures only knew the loss they sustain in the neglect of this plant’ in Guyana it would be consumed more frequently.51 Annie Brassey, in her travel account In the Trades, the Tropics, and the Roaring Forties (1885), writes in detail of the ‘peculiar and beautiful red ovate fruit’:

The akee, a large tree somewhat resembling a mango, bearing glossy green leaves and large pod-shaped fruit. The fruit that was ripe was of a brilliant scarlet or crimson … Its flavour is delicious; but it is not fit to be eaten until it bursts spontaneously, showing its soft, spongy, creamy centre.52

Brassey’s detailed description encompasses not only the appearance and use of the fruit, ‘excellent, either as a vegetable or a fruit’, but also the potential threat of ‘a deadly poison’ after an English family ‘died in less than twenty minutes after eating unripe akees only a few months ago’. Clearly, ackee was known to colonial planters, visitors and settlers in the broader Caribbean region, and appreciated by some, but it did not widely gain approval as a favoured fruit amongst this class. These texts indicate a sense of a struggle to situate the ackee, both in terms of how it was supposed to be consumed and categorised – as a fruit or a vegetable – and where its value lay.

These ambiguities extend from travel writing to literary accounts about ackee. Despite its long-standing prominence in Jamaican culture, ackee is a distinctly ambivalent symbol. In Banana Bottom (1933), Jamaican-American and Harlem Renaissance writer Claude McKay’s novel about the return of Bita Plant to her hometown in Jamaica, a detailed and luxurious description of the ackee is offered through white missionary Priscilla Craig’s impression of the fruit:

The cream-lobed akee – a fruit that was eaten like a vegetable – with its burnished black seeds set in vermilion case, so like an antique flower-shaped brooch fashioned of jet, ivory and coral, and which had seemed so strange to her from her first coming to the colony and after long years still held its strangeness.53

As McKay exemplifies, the language used to describe ackee is varied and often conveys a sense of ‘strangeness’ stemming from confusion and the contradictions inherent in its qualities. Ackee is both fruit and vegetable, both natural and artificial in its jewel-like similarity to a ‘brooch’. It is visually striking in colour and shape, and ambiguous in flavour, described variously as ‘mild’, ‘bland’, ‘rich’, ‘delicate’, ‘nutty’, ‘silky’ and like ‘scrambled eggs’ in texture, as well as avocado, butter and cheese.54

Such literary accounts of ackee demonstrate that it has become a distinctively Jamaican cultural symbol, with its consumption associated especially with a certain daring on the part of Jamaicans. In Abeng (1984), Michelle Cliff writes: ‘Concealed within the fleshy yellow pouches which were edible was a sprinkling of red powder— “deadly poison”. … Jamaicans were the only island people daring enough to eat the ackee.’55 The connection that Cliff draws between the collective personality of Jamaicans and the consumption of a specific fruit offers another suggestion as to why ackee is scarcely discussed in the Miscellaneous Reports, as an example of a food plant acting as a distinctive cultural symbol, accessible only to Jamaicans. Writing similarly of cassava, the ‘bitter’ starchy root with ‘poisonous juices’ which are removed to make cassareep, a syrup used as the basis for Pepper Pot soup, Candice Goucher observes that ‘from the poisonous beginnings of oppression came a resilience and resistance that flavored a distinctively Caribbean attitude’.56 This association of a potentially poisonous plant with resistance parallels Cliff’s representation of the ackee as a symbol of Jamaican daring, and explains why the tree fails to gain the interest of, or is consciously ignored by, the botanists of the Jamaican botanical gardens.

The National Fruit

In honour of its long-term cultural significance, Ackee was enshrined as a symbol of Jamaican independence with its official installation as the national fruit of Jamaica in 1962, alongside other botanical emblems including the national tree the blue mahoe, and the national flower, that of the lignum vitae, which were recommended by the National Flower Committee.57 The committee reported that ‘[t]his fruit selected itself and whilst not indigenous to Jamaica, has remarkable historic associations. It was originally imported from West Africa, probably brought here in a slave ship, and now grows luxuriously producing each year large quantities of edible fruit’. This status not only recognises the cultural agency of the plant itself, but also its historic role in supporting the agency of enslaved people, and its particular association with Jamaica: ‘Jamaica is the only place where the fruit is generally recognised as an edible crop.’ The Gleaner reported the selection of these emblems in March 1962, before independence from Britain, and public opinion was also sought through flower shows.58

For the same reasons ackee was an unlikely plant to be transferred by slave traders, it was not a priority for planters or botanists to cultivate on its arrival in Jamaica. As a prominent fruit tree in Jamaica which was not exported during the colonial era, ackee is set apart from other fruits such as bananas and mangoes by its extremely limited discussion in Kew’s archives. Thus, the argument for ackee’s transfer to the Caribbean as a strong example of African botanical and culinary agency, is likewise one reason for its relative absence in Kew’s Miscellaneous Reports. This absence is still more conspicuous on account of the ubiquity of ackee descriptions elsewhere in writings about Jamaica. But as a tree overlooked and undervalued in the colonial botanic gardens of the island, ackee was left to flourish as an ambivalent symbol of both beauty and threat, signifying the subversive foundations of Jamaican identity, the tree standing, in Suzanne Barr’s memoir My Ackee Tree, ‘like a Jamaican flag in front of our house’.59

Heather Craddock is a Collections Researcher at The National Archives, UK, specialising in colonial environmental history. She holds a PhD in English Literature from the University of Roehampton and the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Her research focuses on archival histories of plants, gardens, and forests particularly in the colonial Caribbean. She co-curated an exhibition on the history of forest conservation, ‘Uprooted’, at Kew Gardens in 2023 and has taught English Literature and Environmental Humanities at Brunel University and the University of Roehampton.

Email: Heather.Craddock@nationalarchives.gov.uk

1 D.M. West, Slave Names Memorialized: A Historical-Linguistic Analysis of Monumented Slave Names in Jamaica. (MA Thesis, University of the West Indies, Mona Campus, 2017), p. 12: ‘The monuments were launched in 2007 as part of a Heritage tribute organized by the UWI and the Jamaica National Bicentenary Committee, in celebration of the 200th anniversary of the 1807 abolition of the slave trade.’

2 MCR/15/3/8, ‘Jamaica: Cultural Products A-F’, Miscellaneous Reports Collection, RBG, Kew Archives, ff. 1–6.

3 B. Higman, Jamaican Food (Kingston: University of the West Indies Press: 2008), p. 155.

4 M. Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), p. 1.

5 S.Hartman, ‘Venus in two acts’, Small Axe 12 (2008): 1–14 (p. 11).

6 S.E. Smallwood, ‘The politics of the archive and history’s accountability to the enslaved’, History of the Present 6 (2016): 117–32 (p. 125).

7 M. Ogborn, ‘Talking plants: Botany and speech in eighteenth-century Jamaica’, History of Science 51 (2013): 251–82 (p. 253).

8 L.L. Schiebinger, Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World (London: Harvard University Press, 2004), p. 226.

9 I discuss this approach to the Miscellaneous Reports in more detail in my Ph.D. research on the subject: H. Craddock, Kew’s Colonial Archive: A Plant Humanities Approach to the Caribbean Miscellaneous Reports, 1850–1928. (Ph.D. thesis, University of Roehampton, 2024). For further discussion of ideas about expanding what constitutes an ‘archive’ for research into the history of the enslaved, see S. Palmié, ‘Slavery, historicism, and the poverty of memoralization’, in S. Radstone and B. Schwarz (eds), Memory: Histories, Theories, Debates (New York: Fordham University Press, 2010); M-R. Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon Press, 2015).

10 ‘Mona Village’ monument, 2007, University of the West Indies Mona, Kingston.

11 ‘Papine Village’ monument, 2007, University of the West Indies Mona, Kingston.

12 MCR/15/3/8, f. 2.

13 Ibid.

14 A. Broughton, Hortus Eastensis: Or, a Catalogue of Exotic Plants Cultivated in the Botanic Garden, in the Mountains of Liguanea, in the Island of Jamaica (Kingston: Alexander Aikman, 1794), p. 11.

15 T. Dancer, Catalogue of Plants, Exotic and Indigenous, in the Botanical Garden, Jamaica (St Jago de la Vega, Jamaica: A. Aikman, 1792), p. 4.

16 MCR/15/3/6, MR 663, Jamaica: Botanic Gardens, f. 97; William Fawcett, ‘The Public Gardens and Plantations of Jamaica’, Botanical Gazette 24 (1897): 345–69 (p. 346).

17 W. Jekyll, Guide to Hope Gardens (Kingston: Aston W. Gardner & Co., 1904), p. 2.

18 Broughton, Hortus Eastensis, p. 11.

19 MCR/15/3/8, f. 2.

20 Higman, Jamaican Food, p. 153.

21 J. Lunan, ‘Hortus Jamaicensis, or A Botanical Description (According to the Linnean System) and an Account of the Virtues, &c., of Its Indigenous Plants Hitherto Known, as Also of the Most Useful Exotics. Jamaica’, St. Jago de la Vega Gazette (1814), p. 9.

22 Higman, Jamaican Food, p. 152.

23 Ibid.

24 E. DeLoughrey, R.K. Gosson and G.B. Handley, Caribbean Literature and the Environment: Between Nature and Culture (University of Virginia Press, 2005), p. 10.

25 J. Carney and R.N. Rosomoff, In the Shadow of Slavery: Africa’s Botanical Legacy in the Atlantic World (L.A.: University of California Press, 2011), p. 135.

26 Ibid., p. 128; see also B.F. Tobin, Colonizing Nature: The Tropics in British Arts and Letters, 1760–1820 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011), p. 62: ‘Out of these gardens, slaves created economic opportunities that ultimately enabled them to resist some of the consequences of slavery and to make the successful transition from slave to peasant economy’.

27 S. Wynter, ‘Novel and history, plot and plantation’, Savacou 5 (1971): 95–102 (p. 99).

28 Higman, Jamaican Food, p. 154.

29 S. Mintz, Caribbean Transformations (New York: Taylor & Francis, 2017), pp. 228–29.

30 MCR/15/3/8, f. 1.

31 Ibid.

32 Bowrey’s report was quoted elsewhere in an article entitled ‘The Ackee’ by John R. Jackson, Curator of Kew’s Museum of Economic Botany, in The Chemist and Druggist, in which Jackson refers to it as the akee-apple: J.R. Jackson, ‘The Ackee’, The Chemist and Druggist 40 (21 May 1892): 749, included in Bulletin of Miscellaneous Information 64 (Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, April 1892), p. 109.

33 J. Rashford, ‘Those that do not smile will kill me: The ethnobotany of the ackee in Jamaica’, Economic Botany 55 (2001): 190.

34 Ibid., 206.

35 Ibid., 202.

36 H.H. Scott, Report on Vomiting Sickness (Kingston, Jamaica: Government Printing Office, 1915), in CO 137/710/25, The National Archives, Kew, ff. 187-201; GB 0809 Scott/01, ‘Correspondence, publications, press cuttings and reports relating to vomiting sickness and ackee poisoning, 1886–1918’, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Archives: these documents include a selection of press cuttings recording responses to Scott’s publications, some of which are supportive of his findings, but many are doubtful of his conclusion that cases of ‘vomiting sickness’ can be directly connected to ackee consumption.

37 C. Goucher, Congotay! Congotay! A Global History of Caribbean Food (Routledge, 2014), p. 130.

38 Ogborn, ‘Talking plants’, 271.

39 Goucher, Congotay! p. 130.

40 Ogborn, ‘Talking plants’, 272.

41 MCR/15/3/8, f. 2.

42 Ibid. For another educational story about ‘Achee-Poison’ for school children, see C.E. Phillips, Tropical Reading Books (London: Griffith and Farran, 1880), pp. 82–84.

43 In contrast, see François-Richard de Tussac’s earlier painting which shows only unripe ackee: F.-R. de Tussac, Flore des Antilles, vol. 1 (Paris: 1808), pl. 3.

44 MCR/15/3/8, f. 2.

45 EBC 53440 Akee Oil and Cake, Jamaica; RBG, Kew, Economic Botany Collection, donated by Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain.

46 MCR/15/3/3, MR 660, Jamaica: Bulletin; Bulletin of the Botanical Department of Jamaica, No. 5 (Jan.1888): 2. For other minor mentions of ackee, see also MCR/15/3/3, Bulletin, No. 3 (Sept. 1887): 6; and MCR/15/3/3, Bulletin, No. 9 (Nov. 1888): 6.

47 DC/207/198, Letter from M. [Michael] Grabham to Sir Arthur William Hill, from Jamaica, 3 May 1924; see also DC/210/497 (Kew Archives, Directors’ Correspondence).

48 W.J. Titford, Sketches Towards a Hortus Botanicus Americanus; Or Coloured Plates (with Concise and Familiar Descriptions) of New and Valuable Plants of the West Indies and North and South America, Etc. (London: Sherwood, Nealy and Jones, 1811), p. xiv; Higman, Jamaican Food, pp. 157–58.

49 Higman, Jamaican Food, p. 158.

50 M.G. Lewis, Journal of a West-India Proprietor: Kept During a Residence in the Island of Jamaica (London: J. Murray, 1834), p. 152.

51 C.D. Dance, Chapters from a Guianese Log-Book (Georgetown, Demerara, 1881), pp. 49–50.

52 A. Brassey, In the Trades, the Tropics and the Roaring Forties (New York: H. Holt, 1885), p. 248.

53 C. McKay, Banana Bottom (London: Pluto Press, 1986), p. 90.

54 Higman, Jamaican Food, p. 155.

55 M. Cliff, Abeng (New York: Penguin Publishing Group, 1995), p. 94: Cliff also includes the folk song ‘Linstead Market’, which begins with the lines ‘Carry me ackee go a Linstead Market / Not a quatty-wuth sell’, p. 82.

56 Goucher, Congotay! p. 128.

57 Higman, Jamaican Food, p. 3; ‘Jamaican national symbols’, https://nlj.gov.jm/jamaican-national-symbols (accessed 16 July 2025).

58 Anon., ‘The choice of national emblems’, The Gleaner, 30 March 1962, p. 12.

59 S. Barr, My Ackee Tree: A Chef’s Memoir of Finding Home in the Kitchen (Toronto: Penguin, 2022).

Figure 1.

Mona Memorial, University of the West Indies, Kingston, Jamaica.

Source: Author’s image.

Figure 2.

Plan of Hope Gardens, Walter Jekyll.

Source: Guide to Hope Gardens, (Kingston: Aston W. Gardner & Co., 1904), p. 2.

Figure 3.

‘Foliage and Fruit of the Akee, Jamaica’, Marianne North, 1872.

Source: Marianne North Gallery, RBG, Kew, MN 137.

Figure 4.

‘Akee Oil and Cake’, Jamaica, EBC 53440, Economic Botany Collection, RBG, Kew.

Source: Author’s Image.