Amanda Blake Davis

Shelley’s Arboreal Poetics of Place and Wordsworth’s

‘Woodland State’

PLANT PERSPECTIVES 2/2 - 2025: 321–336

doi: 10.3197/whppp.63876246815903

Open Access CC BY 4.0 © The Author

ABSTRACT

William Wordsworth, deemed the ‘Poet of Nature’ by Percy Bysshe Shelley, is well known for his affinity with trees. This essay directs attention to Shelley’s arboreal poetics of place through Wordsworthian allusions in Alastor and related compositions. Shelley’s trees branch throughout his various forms of composition, from the drawings of trees in his manuscript notebooks, to rhetorical figures within his poems and descriptions of trees observed in letters. Contrary to Shelley’s apparent rejection of Wordsworth in the Preface to Alastor, the ‘woodland state’ of a related poem, ‘Verses Written on Receiving a Celandine in a Letter from England’, underscores the persisting importance of Wordsworth’s place in Shelley’s arboreal poetics..

Keywords

Percy Bysshe Shelley, William Wordsworth, Romantic Poetry, Poetics, Arboreal Humanities.

William Wordsworth, deemed the ‘Poet of Nature’ by Percy Bysshe Shelley in his sonnet, ‘To Wordsworth’, is well known for his affinity with trees.1 The first-generation English Romantic poet memorialised in verse the ‘Yew-tree, pride of Lorton Vale’ and ‘those fraternal Four of Borrowdale’ in ‘Yew-Trees’.2 In the 1805 Prelude Wordsworth recalls, while a student at Cambridge, ‘A single Tree’: ‘an Ash’

William Wordsworth, deemed the ‘Poet of Nature’ by Percy Bysshe Shelley in his sonnet, ‘To Wordsworth’, is well known for his affinity with trees.1 The first-generation English Romantic poet memorialised in verse the ‘Yew-tree, pride of Lorton Vale’ and ‘those fraternal Four of Borrowdale’ in ‘Yew-Trees’.2 In the 1805 Prelude Wordsworth recalls, while a student at Cambridge, ‘A single Tree’: ‘an Ash’

With sinuous trunk, boughs exquisitely wreathed;

Up from the ground and almost to the top

The trunk and master branches everywhere

Were green with ivy; and the lightsome twigs

And outer spray profusely tipped with seeds

That hung in yellow tassels and festoons,

Moving or still, a Favorite3

_-_Landscape_with_an_Ash_Tree_-_2382_-_Fitzwilliam_Museum.png)

Figure 1.

Antoine Chintreuil, Landscape with an Ash Tree, c. 1850–1857, oil on canvas, 26.7 x 34cm, Fitzwilliam Museum.

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The poet recollects how ‘Oft have I stood / Foot–bound, uplooking at this lovely Tree’ (Book VI, 100–01). Perhaps more memorable still is the ‘dark sycamore’ of ‘Lines written a few miles above Tintern Abbey’ under which the reminiscing poet reflects upon landscapes past and present.4 Despite the diversity of tree species in his poetry, Wordsworth admitted to ‘prefer[ring] [the Scots pine] to all others, except the Oak, taking into consideration its beauty in winter, and by moonlight and in the evening’.5 Varieties of tree species populate Wordsworth’s poetry, sometimes figured as symbols – such as the oak and national liberty – elsewhere reflecting the poet’s interests in planting and botany, and often evocative of place.6 As Alan G. Hill writes, ‘from An Evening Walk onwards’, and by implication, its companion piece, Descriptive Sketches, ‘the “dance” of “stately trees” (in Milton’s phrase) held a special place in [Wordsworth’s] imagination’.7 By contrast, the second-generation Romantic poet Shelley’s arboreal affinities are less noticed.8

The polymathic poet Shelley’s interests were wide-ranging, including ‘[g]eology, astronomy, chemistry, biology’, as Marilyn Gaull notes.9 Despite the absence of botany in this list, plants are abundant in Shelley’s poetry, from the mimosa of ‘The Sensitive-Plant’ to the pumpkin of ‘The Zucca’. As Cian Duffy affirms, ‘Shelley’s notebooks, correspondence, poetry, and prose all reveal a lifelong interest in plants as well as an awareness of and an engagement with botanical discourses and practices’.10 The hundreds of drawings of trees in Shelley’s manuscript notebooks, and the numerous arboreal figures in his poetry, reveal that, like Wordsworth, Shelley shared an especial affinity for trees.

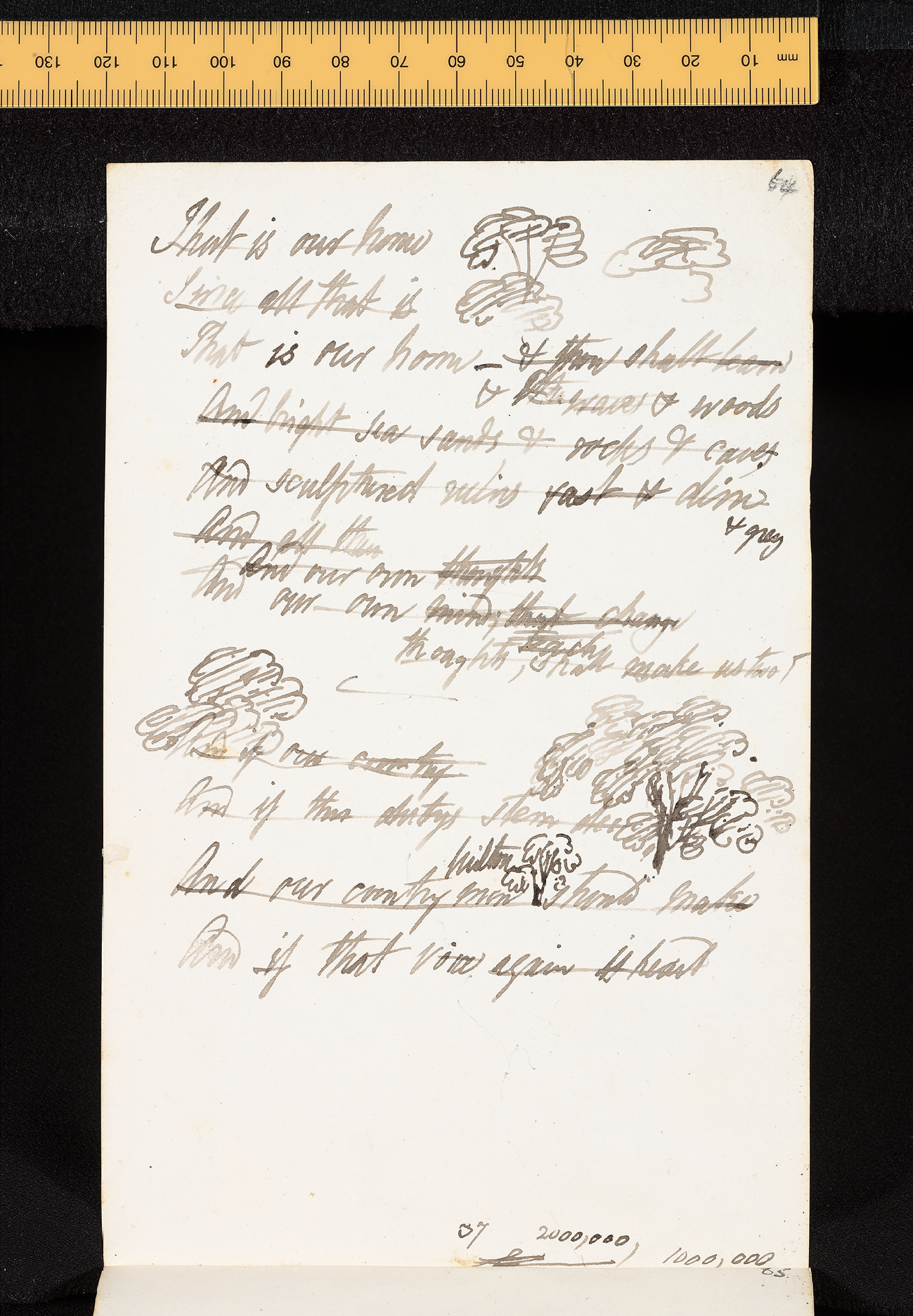

Figure 2.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, Bodleian MS. Shelley adds. e. 16 © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford < https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/e0cec14b-3f7a-43da-9a21-54dfa0b10d1d/>

Shelley’s fleeting, uprooted life contrasts with the long, grounded life of Wordsworth; indeed, Shelley was critical of the older poet’s Tory turncoating and shift from radicalism to conservatism. The poet of poverty and ‘common woes’ celebrated in Lyrical Ballads falls away, in Shelley’s estimation, with the publication of The Excursion in 1814, leaving the younger poet ‘much disapointed’ [sic] (‘To Wordsworth’, 5).11 As G. Kim Blank has it, ‘The Excursion for Shelley represents Wordsworth’s poetic failure’.12 And yet, as the Romantic critic Leigh Hunt noted, Wordsworth and Shelley were ‘two spirits who ought to have agreed’.13 This statement seems especially true in the pair’s proclivity for composing poems featuring trees, and particularly trees involved in the making of place.

In Shelley’s first major work, Alastor; or, The Spirit of Solitude, the young poet pictures a biodiverse treescape wherein place is shaped by arboreal interconnections.

The oak,

Expanding its immense and knotty arms,

Embraces the light beech. The pyramids

Of the tall cedar overarching, frame

Most solemn domes within, and far below,

Like clouds suspended in an emerald sky,

The ash and the acacia floating hang

Tremulous and pale.

(431–438)

‘Few romantic poems convey as much in so small an enclosure of the poetic reach of botanical names’, Theresa M. Kelley writes of this scene.14 Together, the trees’ ‘woven leaves / Make net-work’ (445–46), arboreally echoing the poem’s substance as a ‘woven … net-work’ of allusions. Such Wordsworthian arboreal allusivity is especially evident in Shelley’s evocation of the dying Poet – or ‘wanderer’s’ – resting place: ‘one silent nook’ overseen by a ‘solemn pine’ (626; 572; 571). The Wanderer of Wordsworth’s Excursion remarks,

we die, my Friend,

Nor we alone, but that which each man loved

And prized in his peculiar nook of earth

Dies with him, or is changed15

The Alastor Poet’s deathly resting place seems to combine Wordsworth’s Wanderer’s ‘peculiar nook of earth’ with his Pastor’s account of the ‘tall Pine’ that is both a place of living repose and the grave of ‘a gentle Dalesman’.16 Writing of the poet’s pairing of ‘ash’ and ‘acacia’ in the lines of Alastor quoted above, Nora Crook and Derek Guiton note that Shelley ‘almost never used an image until he was satisfied that it belonged to an authentic part of his own experience and that it was also to be found in myth and great writers of the past’. Thus, while both species of tree grew in ‘Windsor Great Park, said by Mary [Shelley] to be the immediate inspiration of the passage’, the pairing of these species also recalls ‘a list of deciduous trees in Nicholson’s British Encyclopaedia’s section on gardening’; there, Crook and Guiton note, ‘the first two are “acacia, ash” which thus impart a taxonomic nuance to the line, in keeping with the eighteenth-century Miltonising evident in the poem at this point’.17 Wordsworth, as a living poet who is yet ‘morally dead’, is numbered amongst such ‘great writers of the past’ in Alastor.18 Alastor, like its companion piece ‘To Wordsworth’, directly addresses the older poet by way of its slightly misquoted epigraph from The Excursion – ‘“The good die first, / And those whose hearts are dry as summer dust, / Burn to the socket!”’ – through numerous allusions and voicings of Wordsworth’s earlier poetry, and by way of its quasi-allegorical Poet and Narrator figures.19

In Shelley’s dialogic lyric, ‘Two Spirits: An Allegory’, Shelley self-referentially alludes to Alastor by recalling the scene of the Poet’s death, ‘the grey precipice and solemn pine’ (571) in the second spirit’s utterance: ‘Some say there is a precipice / Where one vast pine hangs frozen to ruin’ (33–34). Within the margins of the manuscript, Shelley also alludes to Alastor and intellectually engages with Wordsworth by again writing the slightly misquoted lines from The Excursion used to close the earlier poem’s preface at the top of the page: ‘The good die first—’; ‘Wordsworth was clearly in his thoughts’, Michael O’Neill affirms.20 The root of poetry, poiesis, itself means ‘making’; trees, for Wordsworth as for Shelley, are integral to the making of place.21 John C. Ryan, in describing the plant-human relations of ‘phytopoetics’, ‘underscores the potential for human becoming to harmonize with the poiesis – the dynamic transformation – of vegetal life over time, through the seasons, and grounded in places’.22 Such a harmonising of plants with place propels Shelley’s poetic relationship with Wordsworth.

Shelley’s most condensed evocation of Wordsworthian vegetal place occurs in the Alastor Poet’s journey toward the biodiverse treescape and deathly nook. Approaching the place

Where the embowering trees recede, and leave

A little space of green expanse, the cove

Is closed by meeting banks, whose yellow flowers

Forever gaze on their own drooping eyes,

Reflected in the crystal calm. The wave

Of the boat’s motion marred their pensive task,

Which nought but vagrant bird, or wanton wind,

Or falling spear-grass, or their own decay

Had e’er disturbed before. The Poet longed

To deck with their bright hues his withered hair

(404–413)

The downward gazing yellow flowers are recognisably Narcissus; in this place-image, Shelley recalls Wordsworth’s ‘host of dancing Daffodils; / Along the Lake, beneath the trees’ in whose company the poet ‘gazed—and gazed’.23 Shelley shifts Wordsworth’s gazing from the act of the poet to the act of the yellow flowers, underscoring the mythological origins of Narcissus’s fatal floral transformation.24 Shelley’s addition of ‘falling spear-grass’ to this scene conflates ‘I wandered lonely as a Cloud’ with The Excursion by way of Wordsworthian allusion. Wordsworth’s description of Margaret’s ruined cottage in The Excursion emphasises the vitality of vegetal overgrowth: the ‘plants, and weeds, and flowers, / And silent overgrowings’ that ‘still survived’ Margaret’s death.25 Notably, ‘high spear-grass’ features amidst this vegetal overgrowth. Shelley’s inclusion of daffodils and spear-grass in this scene’s vegetal evocation of Wordsworthian place bespeaks the young poet’s absorption in his older peer’s poetry, despite his failings. Shelley’s transformation of Wordsworth’s ‘high spear-grass’ into ‘falling spear-grass’ may underscore his disappointment in The Excursion and the older poet’s descent from his prior glory. Nonetheless, as Madeleine Callaghan notes, ‘[t]hat Shelley so frequently returned to The Excursion as a point of departure far beyond 1814 for his philosophical, poetic, and intellectual preoccupations suggests its centrality to his poetic thought’.26

Presaging his self-exile to Italy, Shelley’s excursions to the continent in 1814 and 1816 – memorialised in Mary and Percy Shelley’s collaborative travelogue, History of a Six Weeks’ Tour through a Part of France, Switzerland, Germany, and Holland, published in 1817 – may recall Wordsworth’s 1790 tour of revolutionary France, Switzerland, Italy and Germany, synthesised into the walking tour that is described in Descriptive Sketches, published in 1793. ‘Through personification and animism the poet makes a separate (visual) entity of everything his glance encounters’, Geoffrey Hartman writes of Wordsworth’s ‘poem of “place”’.27 ‘Descriptive Sketches, therefore, is not a portrait of nature, or the projection on nature of an idea, but the portrayal of the action of a mind in search (primarily through the eye) of a nature adequate to its idea’, Hartman continues.28 In this early poem, trees are concomitant in the poiesis of place as Wordsworth conjures the ‘chestnut groves’ of Como, and ‘Locarno smiles / Embowered in walnut slopes and citron isles’.29 Shelley’s recollections of his own continental travels in History of a Six Weeks’ Tour also convey such senses of place through visual and verbal portraits of trees. ‘Descriptive Sketches evokes the visual immediacy of an artist’s sketchbook’, Fiona Stafford writes.30 But, while Wordsworth in Descriptive Sketches paints his tree-adorned scenes solely through verse – heroic couplets – Shelley’s manuscripts offer pictures of the poet’s mind in action through hundreds of drawings of trees.

Writing to his friend, Thomas Love Peacock, from Geneva in 1816, Shelley reflects upon his impending return to England:

—like Wordsworth he will never know what love subsisted between himself and [England], until absence shall have made its beauty heartfelt. Our Poets & our Philosophers our mountains & our lakes, the rural lanes & fields which are ours so especially, are ties which unless I become utterly senseless can never be broken asunder.31

Months later, Shelley again writes in mind of England: ‘Tell me of the political state of England—its literature […] I trust entirely to your discretion on the subject of a house. Certainly the Forest engages my preference, because of the sylvan nature of the place’.32 The ‘magnificent and unbounded forests’ of the Alpine landscapes, ‘to which England affords no parallel’, nonetheless repeatedly return Shelley’s thoughts to the scenes of his homeland, of which ‘Our Poets & our Philosophers’ – one might here substitute the words ‘Wordsworth’ and ‘Coleridge’ – are a vital part.33 Musing on the Swiss forest as a site underwritten with literary associations, Shelley describes how ‘the trees themselves were aged, but vigorous, and interspersed with younger ones, which are destined to be their successors, and in future years, when we are dead, to afford a shade to future worshippers of nature, who love the memory of that tenderness and peace of which this was the imaginary abode’.34 Shelley subtly reads his relationship with Wordsworth in treescapes such as these. The shade of Wordsworth as ‘A worshipper of Nature’, as the older poet identifies himself in ‘Tintern Abbey’, is recast in Shelley’s ‘shade to future worshippers of nature’, where the younger poet darkly numbers himself amongst Wordsworth’s future ‘successors’.35

Perhaps surprisingly, it is a flower, rather than a tree, that is outrightly symbolic of Wordsworth for Shelley.36 ‘We have bought some specimens of minerals and plants, and two or three crystal seals, at Mont Blanc, to preserve the remembrance of having approached it’, Shelley writes to Peacock:

There is a cabinet of Historie Naturelle at Chamouni, just as at Keswick, Matlock, and Clifton … The most interesting of my purchases is a large collection of all the seeds of rare alpine plants, with their names written upon the outside of the papers that contain them. These I mean to colonize in my garden in England, and to permit you to make what choice you please from them. They are companions which the Celandine—the classic Celandine, need not despise; they are as wild and more daring than he, and will tell him tales of things even as touching and sublime as the gaze of a vernal poet.37

Shelley’s gendering and personification of the Celandine recall Wordsworth’s self-identification with the English Celandine in his 1807 collection, Poems, In Two Volumes, which featured poems on the namesake flower including ‘To the Small Celandine’ and ‘To the same Flower’. In the former poem, Wordsworth declared: ‘There’s a flower that shall be mine, / ‘Tis the little Celandine’, forming a botanical self-association that Shelley alludes to in his letter.38

_(8746622717).jpg)

Figure 3.

Edward Step, ‘Lesser Celandine. Pilewort. Ranunculus ficaria’ in Wayside and Woodland Blossoms: A Pocket Guide to British Wild-flowers for the Country Rambler (1895).

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Shelley’s letter, written to Peacock in Marlow, is linked to a poem left unpublished in Shelley’s lifetime, ‘Verses Written on Receiving a Celandine in a Letter from England’.

I thought of thee, fair Celandine,

As of a flower aery blue

Yet small—thy leaves methought were wet

With the light of morning dew.

In the same glen thy star did shine

As the primrose and the violet,

And the wild briar bent over thee

And the woodland brook danced under thee.

(1–8)

Like his evocation of a distinctively Wordsworthian place in Alastor through the pairing of daffodils with spear-grass, here, Shelley alludes to Wordsworth’s self-identification with the Celandine by drawing upon the older poet’s own botanical descriptions. In ‘To the Small Celandine’, Wordsworth writes:

Long as there’s a sun that sets

Primroses will have their glory;

Long as there are Violets,

They will have a place in story:

There’s a flower that shall be mine,

’Tis the little Celandine.39

Shelley’s ‘Verses’ transplant Wordsworth’s Celandine amidst its companions – the Primrose and the Violet – along with the flowers’ luminosity. The letter and poem, both composed in the summer of 1816, seem to respond to a letter sent to Shelley on the continent by Peacock, apparently containing a pressed celandine.40 Both letter and poem share the image of Peacock as priest of Nature, where Shelley assigns ‘the functions of a priest’ to Peacock in the former, tasking him with finding the poet a house with a large garden in the ‘sylvan nature’ of the forest, and likens him to ‘that priest of Nature’s care / Who sent thee forth to wither’, in the verses addressed to the Celandine (67–68).41 The satirical tone of Shelley’s verses condemn Wordsworth for being ‘morally dead’, for becoming a poet of profit: ‘He is changed and withered now, / Fallen on a cold and evil time’ (29–30).42 Although Wordsworth is symbolically associated with the withered Celandine in Shelley’s verses, the poets’ arboreal affinities surface as Shelley yearns for his Wordsworth-as-Celandine to return to his ‘woodland state’ (34).

Celandine! Thou art pale and dead,

Changed from thy fresh and woodland state.

Oh! that thy bard were cold, but he

Has lived too long and late.

(33–36)

‘In many ways the terms woodlands and forests are interchangeable’, Owain Jones and Paul Cloke write; ‘But in other ways they do carry distinct resonances that vary across cultures’. For Jones and Cloke, ‘[t]he category of woodland suggests a more intimate, culturalized space than is the case with forest. This is particularly so in Britain’.43 Shelley’s yearning for Wordsworth-as-Celandine’s return to a ‘woodland state’ contrasts with the plucked, pressed flower’s current state, ‘disunited’ from the ‘vernal poet’ (65). Shelley’s repeated choice of ‘woodland’ in ‘Verses Written on Receiving a Celandine’ seems to suggest such a sense of intimacy with Wordsworth as poet, and as a distinctively English poet. ‘Trees span many lifetimes and have always been used as historical markers’, Richard Hayman writes, ‘bringing the past closer to the present’; the ‘woodland state’ of Shelley’s Celandine fosters such a conflation – and yet, a bifurcation – of time and place.44

The list of Alpine plant seeds is a further accompaniment to this pairing of letter and poem, where the ‘rare alpine plants’ that Shelley intends to ‘colonize’ his garden in Marlow are described as companions to the Celandine.45 On the final page of Shelley’s list of Alpine plants, a drawing of a woodland scene appears, where a variety of trees and shrubs cluster into the margins. Shelley’s trees branch throughout his various forms of composition, from the Gilpinesque landscape drawings of trees in his manuscript notebooks, to rhetorical figures within his poems, to descriptions of trees observed in letters and within the list of Alpine seeds that the poet intended to cultivate in his garden in Marlow. Shelley’s ‘woodland state’ emphasises the persisting importance of Wordsworth’s place in Shelley’s arboreal poetics.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Portions of this essay stem from talks given by the author at the English Literature Research Seminar in the Centre for Languages and Literature, Lund University, Sweden in 2024; the ‘Tree Cultures: Words, Woods and Well-Being’ conference at the Linnean Society of London in collaboration with the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, in 2024; and the Wordsworth Summer Conference in 2023. The author wishes to thank the organisers of these events and the editors of this volume.

Amanda Blake Davis is a Lecturer in English Literature at the University of Derby specialising in Romantic poetry, particularly the work of Percy Bysshe Shelley. She is preparing her first monograph, Shelley and Androgyny, alongside a project on Shelley and trees. With Anna Burton, she is co-editing the collection, Romantic Trees: The Literary Arboretum, 1740–1840 (forthcoming, Liverpool University Press). In 2024, Davis and Burton co-organised the one-day event, ‘Tree Cultures at Kew’, at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, with the support of Caroline Cornish. Davis and Burton launched the ‘Tree Cultures Network’ during this event to foster interdisciplinary collaborations in the arboreal humanities.

Email: a.davis2@derby.ac.uk

ORCiD: 0000-0001-7908-8858

1 Percy Bysshe Shelley’s works are quoted from The Major Works, ed. by Z. Leader and M. O’Neill, second edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

2 William Wordsworth’s poetry is quoted from The Major Works, ed. by S. Gill, revised edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), unless stated otherwise. ‘Yew-Trees’, 1; 14.

3 Wordsworth, The Prelude, Book VI, 90–98.

4 Wordsworth, ‘Tintern Abbey’, 10.

5 Quoted in P. Dale and B.C. Yen, Versed in Living Nature: Wordsworth’s Trees (London: Reaktion Books, 2022), p. 79.

6 On Wordsworth’s symbolic and iconographic associations of trees, see in particular T. Fulford, ‘Cowper, Wordsworth, Clare: The politics of trees’, The John Clare Society Journal 14 (1995): 47–59; B.C. Yen, ‘The political iconography of trees in The Excursion’, Textual Practice 31 (7) (2017): 1253–75; and B.C. Yen, ‘The political iconography of trees in Wordsworth’s The Prelude’, The Explicator 74 (1) (2016): 55–60. On Wordsworth’s tree planting, see in particular A. Burton, ‘Planting for “posterity”: Wordsworthian tree planting in the English Lake District’, Nineteenth-Century Contexts 46 (4) (2024): 513–526.

7 A.G. Hill, ‘The “poetry of trees” and Wordsworth’s new vision of pastoral: An unrecorded letter’, Philological Quarterly 81 (2) (2002): 235–45, here p. 235.

8 For recent attention to Shelley’s trees, see A.B. Davis, ‘“—and so this tree— / O that such our death may be—”: Shelley’s last treescapes’, Romanticism 30 (1) (2024): 56–67.

9 M. Gaull, ‘Shelley’s sciences’, in M. O’Neill and A. Howe (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Percy Bysshe Shelley (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 588.

10 C. Duffy, ‘Wild plants and wild passions in Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poems for Jane Williams’, in M. Poetzsch and C. Falke (eds), Wild Romanticism (London and New York, NY: Routledge, 2021), p. 92. Duffy defines this genre as ‘Shelley’s botanical poetry: poems which not only have a plant as their ostensible subject, or which develop extended plant imagery, but which also engage, either explicitly or implicitly, with contemporary botanical discourses and practices’, p. 91.

11 M. Shelley, The Journals of Mary Shelley, P.R. Feldman and D. Scott-Kilvert (eds), 2 vols (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), vol. 1, p. 25.

12 G.K. Blank, Wordsworth’s Influence on Shelley: A Study of Poetic Authority (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1988), p. 207.

13 L. Hunt, ‘Review of Rosalind and Helen, a Modern Eclogue; with other Poems’, The Examiner, 9 May 1819, p. 302.

14 T.M. Kelley, Clandestine Marriage: Botany and Romantic Culture (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), p. 256.

15 William Wordsworth, The Excursion, qtd. in Jared Curtis, (ed.), The Poems of William Wordsworth: Collected Reading Texts from the Cornell Wordsworth, 3 vols (Penrith: Humanities-Ebooks, 2009; repr. 2011), vol. 2, Book I, 502–05.

16 Wordsworth, The Excursion, Book VII, 413; 417.

17 N. Crook and D. Guiton, Shelley’s Venomed Melody (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), pp. 129–30.

18 Shelley, Preface to Alastor, p. 93.

19 The Wordsworthian import of both Poet and Narrator has been much discussed; see, for example, Y.M. Carothers, ‘Alastor: Shelley corrects Wordsworth’, Modern Language Quarterly 42 (1) (1981): 21–47; P. Mueschke and E.L. Griggs, ‘Wordsworth as the prototype of the poet in Shelley’s Alastor’, PMLA 49 (1) (1934): 229–45; E.R. Wasserman, Shelley: A Critical Reading (Baltimore, MD and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1971).

20 M. O’Neill, Shelleyan Reimaginings and Influence: New Relations, second edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023), p. 96.

21 ‘Both “poetics” and “poetry” derive from the classical Greek word poiesis, meaning “making”; the prefix “eco” goes back to “oikos,” which means “household” or “family.” “Ecopoetics” is therefore, as Jonathan Bate proposes in The Song of the Earth, the making of “a dwelling place”’, ‘Introduction’ to J. Fiedorczuk, M. Newell, B. Quetchenbach and O. Tierney (eds), The Routledge Companion to Ecopoetics (New York, NY and London: Routledge, 2024), p. 1.

22 J.C. Ryan, ‘Phytopoetics: Human-plant relations and the Poiesis of vegetal life’, in Fiedorczuk et al. (eds), The Routledge Companion to Ecopoetics, p. 118.

23 Wordsworth, ‘I wandered lonely as a Cloud’, 4–5; 11.

24 On the significance of the Narcissus and Echo myth to Alastor, see S. Fischman, “Like the sound of his own voice”: Gender, audition, and echo in Alastor’, Keats-Shelley Journal 43 (1994): 141–69.

25 Wordsworth, The Excursion, Book I, 964–65.

26 M. Callaghan, ‘Shelley’s Excursion’, Studies in English Literature 60 (4) (2020): 717–37, here p. 733.

27 I borrow this phrase, ‘poem of “place”’, and its contrast to ‘landscape poem’, from Fiona Stafford’s description of ‘Tintern Abbey’. Stafford reads the passage of five years in ‘Tintern Abbey’ alongside the five-year span since the publication of Descriptive Sketches and An Evening Walk, F. Stafford, ‘Wordsworth’s poetry of place’ in R. Gravil and D. Robinson (eds), The Oxford Handbook of William Wordsworth (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), pp. 309–24, here pp. 310 and 311.

28 G.H. Hartman, ‘Wordsworth’s Descriptive Sketches and the growth of a poet’s mind’, PMLA 76 (5) (1961): 519–27, here p. 522.

29 William Wordsworth, Descriptive Sketches, qtd. in J. Curtis (ed.), The Poems of William Wordsworth: Collected Reading Texts from the Cornell Wordsworth, 3 vols, revised edition (Penrith: Humanities-Ebooks, 2011), vol. 1, 81; 176–77.

30 Stafford, ‘Wordsworth’s poetry of place’, p. 315

31 Percy Bysshe Shelley, The Letters of Percy Bysshe Shelley, F.L. Jones (ed.), 2 vols (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1964), vol. 1, p. 475.

32 The Letters of Percy Bysshe Shelley, vol. 1, p. 490.

33 Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Shelley, History of a Six Weeks’ Tour, Jonathan Wordsworth (ed.) (Oxford and New York, NY: Woodstock Books, 1991), pp. 119–20.

34 History of a Six Weeks’ Tour, p. 132.

35 Wordsworth, ‘Tintern Abbey’, 153.

36 Wordsworth’s arboreal, rather than floral, self-association appears in ‘To a Butterfly’ – ‘My trees they are, my Sister’s flowers’, 11 – but elsewhere, as in ‘To the Small Celandine’, Wordsworth identifies with flowers.

37 History of a Six Weeks’ Tour, pp. 170–72.

38 Wordsworth, ‘To the Small Celandine’, 7–8.

39 Ibid.

40 See G.K. Blank, ‘Shelley’s Wordsworth: The desiccated celandine’, English Studies in Africa 29 (2) (1986): 87–96 and M.A. Quinn, ‘Shelley’s “Verses on the Celandine”: An elegiac parody of Wordsworth’s early lyrics’, Keats-Shelley Journal 36 (1987): 88–109. On Shelley’s colouring of his celandine blue, and not yellow, Michael O’Neill notes ‘PBS’s phrase “the classic celandine” in his above-quoted letter to Peacock, a Classical scholar, one might also observe that there is a blue-coloured celandine in Theocritus’s Idyll XIII.41, and gloss the opening lines as follows: “When I received a withered specimen of a Celandine, I thought of an ideal Celandine—classically blue, and unwithered”’, The Complete Poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley, N. Fraistat and N. Crook (eds), 4 vols to date (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), vol. 3, p. 535.

41 The Letters of Percy Bysshe Shelley, vol. 1, p. 490.

42 Shelley, Preface to Alastor, p. 93.

43 O. Jones and P. Cloke, Tree Cultures: The Place of Trees and Trees in their Place, revised edition (London and New York, NY: Routledge, 2020), p. 26.

44 R. Hayman, Trees: Woodlands and Western Civilization (London and New York, NY: Hambledon and London, 2003), p. 1.

45 As noted by Tatsuo Tokoo, ‘this list might have had something to do with ideas for planting the garden of the new house at Marlow in spring 1817’, The Bodleian Shelley Manuscripts, vol. XXIII, ed. by T. Tokoo and B.C. Barker-Benfield with D.H. Reiman (London and New York: Routledge, 2002), p. 74.