Kate Teltscher

Amherstia Nobilis: High priest of the Vegetable World

PLANT PERSPECTIVES 2/2 - 2025: 337–363

doi: 10.3197/whppp.63876246815904

Open Access CC BY 4.0 © The Author

ABSTRACT

The thawka-gyi or Amherstia nobilis (‘Pride of Burma’) was first encountered by Europeans in 1826, after the First Anglo-Burmese War. This article is the first full-length attempt to recover the European cultural and colonial history of Amherstia nobilis. This splendid tree was known only in cultivated form, planted in the vicinity of Buddhist temples. From the earliest sighting, Western botanists called it the world’s most beautiful flowering tree. The tree’s European reputation was established through narrative accounts and illustrations based on Indian botanical paintings. Wealthy British horticulturalists, attracted by the tree’s beauty, rarity and sacred associations, competed to secure specimens and bring it to flower. Western women horticulturalists, writers and artists were particularly drawn to the plant. In tracing the cultural history of Amherstia nobilis, this article highlights the role of both Indian painters and British women in constructing scientific and horticultural knowledge.

KEYWORDS

Amherstia nobilis, Pride of Burma, Myanmar, Nathaniel Wallich, colonial botany, encounter narratives, Indian botanical art, women in horticulture

ntroduction

ntroduction

Over the course of the nineteenth century, the thawka-gyi or Amherstia nobilis, a magnificent flowering tree from Burma (now Myanmar), was transformed for Europeans from remote wonder to hothouse showpiece.1 According to John Crawfurd, the British envoy who first encountered the thawka-gyi in 1826, it was ‘too beautiful an object to be passed unobserved, even by the uninitiated in botany’.2 With its hanging racemes of scarlet flowers, over a foot long, Amherstia nobilis became famous as the world’s most beautiful flowering tree. It was also one of the rarest. The few known individuals were cultivated specimens, planted close to Buddhist temples, where the splendid flowers were presented as offerings at shrines. The thawka-gyi rarely sets viable seeds so the main means of propagation was air layering. Today, the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species lists the tree as Extinct in the Wild.3

This article is the first full-length attempt to recover the European cultural and colonial history of Amherstia nobilis (commonly known as the ‘Pride of Burma’ or ‘Queen of Flowering Trees’).4 The tree’s renown rests on Nathaniel Wallich’s carefully crafted narrative in Plantae Asiaticae Rariores (1830–32), with its magnificent lithographs based on paintings by the Indian artist, Vishnuprasad. As Kapil Raj and Henry Noltie have demonstrated, Indian plant collectors and artists were integral to the production of botanical knowledge in South and South-East Asia.5 Wallich’s account of his early encounter with the plant ‘not in a state of wildness, but of abandoned cultivation’ in a ruined Buddhist monastery garden served to enhance the exotic allure of Amherstia nobilis with its sacred associations.6

In the nineteenth century, botany was one of the few scientific activities available to women, both in Britain and the colonies.7 This article foregrounds the contribution of women horticulturalists, artists and writers in the cultivation and European understanding of Amherstia nobilis. The pursuit of exotic horticulture was framed as patriotic and imperial service: Louisa Lawrence, who succeeded in bringing Amherstia nobilis to flower, presented the first raceme to Queen Victoria. Subsequent specimens were distributed by Kew Gardens to colonial botanic gardens across the globe.

The tree’s rise to fame in Britain coincided with the East India Company’s exploitation of Burmese teak forests. The history of Amherstia nobilis highlights the relationship between the pursuit of exotic specimens and deforestation. The celebration of Amherstia nobilis as the ultimate ornamental tree served to deflect attention away from the Company’s later large-scale extraction of timber from Burma.

Sourcing teak

Like many nineteenth-century botanical novelties, Amherstia nobilis was first encountered in the aftermath of war.8 In 1824, a border incursion by Burmese forces provided the British East India Company with a pretext for the expansion of Company influence in Burma. After two years of fighting and heavy loss of life, the Company managed to defeat the Burmese. Under the terms of the treaty of Yandabo, the Burmese were required to pay an impossibly large indemnity of £1 million in silver to the East India Company, cede Arakan and Tenasserim provinces, accept a British resident at the court of Ava (Inwa) and sign a commercial treaty.

The leader of the Company mission sent to negotiate the trade treaty was John Crawfurd, an experienced diplomat and administrator. Accompanying him was Nathaniel Wallich, the Danish superintendent of the Company’s Botanic Garden at Calcutta. The East India Company, which had already largely exhausted the teak forests in its Indian territories, was keen to identify Burmese sources of timber, particularly teak. To this end, Wallich was tasked with conducting a survey of teak forests on the trip. Since waterways were essential to convey felled timber, Wallich concentrated on areas along the Salween (Thanlwin) and Ataran rivers. The Company instructed Wallich to assess the suitability of the teak both for naval and military purposes (for instance, in the construction of gun carriages). The newly acquired Burmese forests were evaluated as an economic resource and means to strengthen East India Company power in Asia.

In his report, Wallich warned that no forest was inexhaustible. To guard against over-exploitation, he advised that the forests should be the exclusive property of the state, with strict regulations to ensure that only mature trees were felled, and that teak plantations should be established. Such plantations, he assured the Navy Board in 1831, would provide the British Navy with ‘a permanent supply of the very best timber in the world’.9 However, Wallich’s advice went unheeded and, after two years, the forests were thrown open to private enterprise. As Wallich had predicted, within a couple of decades, the easily accessible teak forests were destroyed.10 The dangers of deforestation were apparent from the very start of British involvement in Burma.

Publicising Amherstia nobilis

Newly accessible regions held a special allure for the botanist, providing the opportunity to collect and record species previously unknown to European science. Alongside his study of the forests, Wallich conducted a botanical survey of the area. Wallich employed a team of collectors attached to the Calcutta Botanic Garden to gather plant specimens, including Akkul Mahmud, William Gomez and Henry Bruce.11 To record the plants, five Indian artists accompanied the party, among them the Botanic Garden’s chief painter, Gorachand, who sadly died during the trip, and his successor, Vishnuprasad.

Wallich was delighted by the rich Burmese flora. The ‘botanical treasures are most extensive’, Wallich reported in a letter read out to London’s Linnean Society in February 1828, ‘the number of species having long ago surpassed 2,000’. But one plant was singled out for praise as the ultimate ornamental tree. Wallich had ‘never seen any vegetable production equal to his Amherstia nobilis when in full bloom’, the Linnean Society members were told. ‘It surpasses all the Indian plants.’ 12

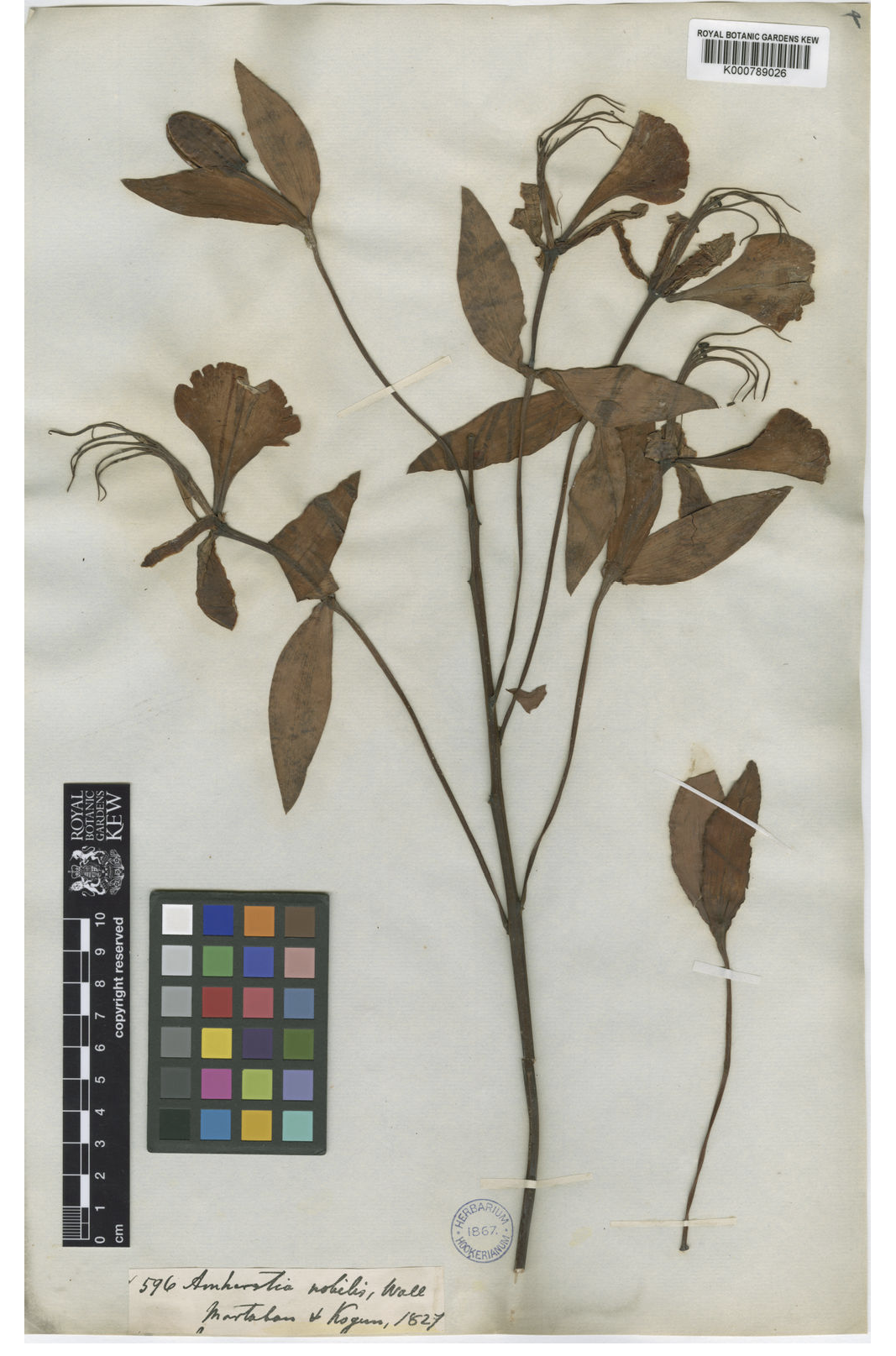

Figure 1.

Amherstia nobilis, Wallich Herbarium, K000789026, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

Wallich himself arrived in London later that year on a period of sick leave. He was accompanied by plant collector William Gomez and an extraordinary haul of dried plant specimens – thirty barrel-loads, weighing twenty tons – collected in India, Burma, Nepal and Singapore. Throughout his career, as David Arnold has argued, Wallich used plants ‘as a form of personal and professional capital’ to gain patronage and promote his social and scientific standing.13 With the help of botanists across Europe, Wallich arranged the collection into sixty duplicate sets. Wallich presented the top set (the ‘Wallich Herbarium’) to the East India Company, which gave the collection to the Linnean Society which, in turn, donated it to Kew. (See Figure 1.)

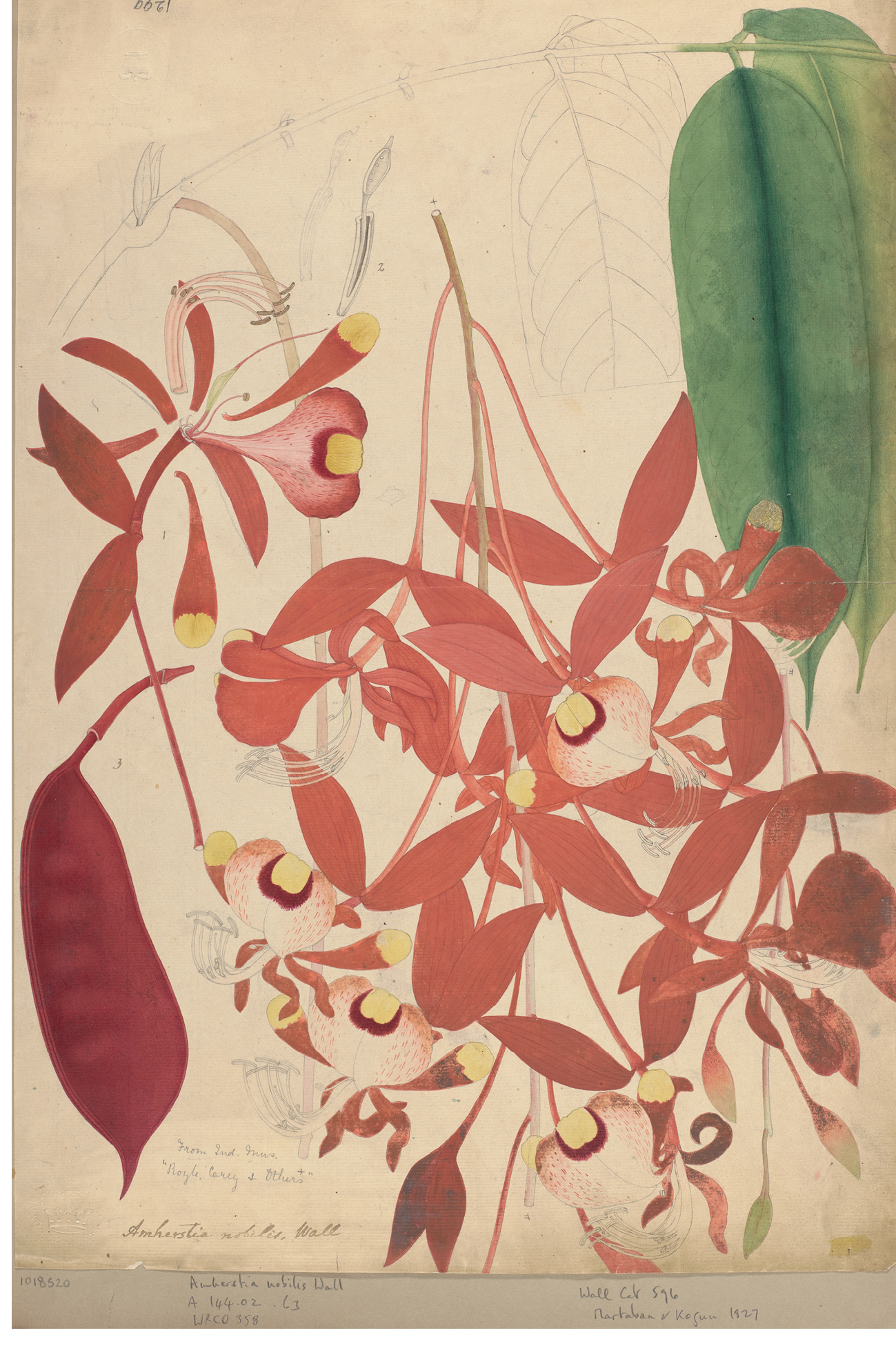

Wallich also brought with him an extensive collection of drawings produced by Indian artists associated with the Calcutta botanic garden. A large part of the ‘Royle, Carey and Others’ collection, initially stored in the East India Company India Museum, now held at Kew, has recently been identified by Henry Noltie as the working drawings used as the basis for the lavish three-volume Plantae Asiaticae Rariores, with over 250 plates, which Wallich published between 1830 and 1832.14 Vishnuprasad’s original paintings remain remarkably vivid today. Probably produced in situ in Burma, the paintings capture the tree’s cascading flowers with vitality and precision. (See Figures 2 and 3.)

Figure 2

Amherstia nobiliis, drawing by Vishnuprasad, WRCO 357, RBG Kew.

Figure 3

Amherstia nobiliis, drawing by Vishnuprasad, WRCO 358, RBG Kew.

Wallich accorded Vishnuprasad’s illustrations of Amherstia nobilis pride of place as the first two plates in the first volume of Plantae Asiaticae Rariores (1830–32). (See Figures 4 and 5.) The publication was the culmination of Wallich’s botanical labours. Dedicated to the Chairman and Directors of the East India Company, the book had a long list of subscribers, headed by members of the royal family and aristocracy, Company servants, European botanists and booksellers and, notably, Indian members of the Agricultural and Horticultural Society of India.15 Individual entries for species comprised botanical illustrations with Latin descriptions, followed by accounts of the plant’s utilitarian or horticultural qualities. The accounts often included a tribute to (or dispute with) fellow botanists. The impressive hand-coloured lithographic plates which, unusually, credit the Indian artists by name, were prepared by the Maltese lithographer, Maxim Gauci, and were hailed in the Gardeners’ Magazine in 1838 as heralding ‘a new era in the art of pictorial illustration’.16

_+Pl.+1.+RBG,+Kew..jpg)

Figure 4.

Amherstia nobilis, hand-coloured lithograph by Maxim Gauci, based on drawing by Vishnuprasad, Nathaniel Wallich, Plantae Asiaticae Rariores 1 (1830): Pl. 1. RBG Kew.

_+Pl.+2,+RBG,+Kew..jpg)

Figure 5.

Amherstia nobilis, hand-coloured lithograph by Maxim Gauci, based on drawing by Vishnuprasad, Nathaniel Wallich, Plantae Asiaticae Rariores 1 (1830): Pl. 2. RBG Kew.

Spectacular in themselves, the impact of the images was enhanced by the accompanying narrative of Wallich’s encounter with Amherstia nobilis. The account was not, in fact, of Wallich’s first sight of the tree which, as he mentions in passing, had occurred in the port city of Martaban (Mottama). Rather than describe a mundane urban specimen, Wallich dwelt on two trees located in the far more romantic setting of a ruined monastery garden, near the Buddhist cave temple of Kogun (Kaw Gon). Wallich’s account of the garden encounter heightened the tree’s exotic appeal. So great was the attraction of the location that, in subsequent retellings of the Amherstia nobilis tale, the monastic garden became the site of first encounter. The trees, Wallich wrote,

were profusely ornamented with pendulous racemes of large vermilion-coloured blossoms, forming superb objects, unequalled in the Flora of the East Indies and, I presume, not surpassed in magnificence and elegance in any part of the world.17

Wallich’s bold assertion of the tree’s world-beating beauty was followed by an equally confident act of naming: ‘I call this tree Amherstia nobilis’.18 Wallich explained that the tree was named in honour of Countess Amherst and Lady Sarah Amherst, both enthusiastic botanists, the wife and daughter of Lord Amherst, the Governor-General of India who was responsible for declaring war on Burma (and who himself had a town and district in Burma named after him). Rather unusually, Amherstia was named after two individuals, both women, with the suggestion that the ladies’ rank dignified the plant, for Amherstia was nobilis, noble.

Although Wallich claimed the right to name the tree (and reap the rewards of Amherst patronage), he noted the local name of Thoka (thawka). Wallich also acknowledged the devotional use of the blossoms, ‘carried daily as offerings to the images in the adjoining caves’.19 Wallich’s account of the blossoms laid at the Kogun shrine linked the tree to the gilded and silver Buddhist statues which, as Sujit Sivasundaram has noted, were favourite items of loot during the Anglo-Burmese war. The tree, as Sivasundaram points out, was commodified as a form of ‘natural historical plunder’.20

Wallich’s attempts to gather information about the tree’s wild origins were unsuccessful. ‘Neither the people here nor at Martaban could give me any distinct account of its native place of growth’, he complained. The tree was ‘not even known by name at the capital of the Burma empire’. This lack of recognition he interpreted, not as evidence of the tree’s limited range, but as ‘a striking instance of the profound ignorance and indifference of that nation concerning all matters connected with the natural productions of their country, notwithstanding the unblushing pretensions of the higher classes’.21 This outburst of contempt seems related to Wallich’s sense of scientific frustration. Wallich was careful to record the geographical locality of plants collected in the wild – an important aspect both of colonial botanical surveys and emergent theories of biogeography. The reluctance to provide information might, of course, have been an act of political resistance on the part of the Ava court. The Burmese monarch traditionally enjoyed rights of ownership over the forest and exercised a monopoly over forest products.22 There would have been good reasons to withhold information about valuable natural resources from envoys of the East India Company.

Despite Wallich’s dismissive view of the current state of Burmese plant knowledge, he did pay a (somewhat condescending) compliment to the past knowledge of Buddhist monks. Observing the pairing of Amherstia nobilis with Saraca asoca (Ashoka) in the monastery garden, Wallich reflected that it

is not a little remarkable, that the priests in these parts should have manifested so good a taste as to select two sorts of trees as ornaments to their objects of worship, belonging to a small but well-marked and extremely beautiful group in the extensive family of Leguminous plants.23

Burmese monks, as Wallich conjectured, might well have considered the two trees as related. In the Burmese language, the same name thawka is used for Amherstia nobilis and Saraca asoca (and for a third species, Saraca indica). The word thawka derives from the Sanskrit aśoka or Pali asoka (the Ashoka tree), which means ‘without sorrow’.24 While both trees are considered as Ashoka trees, sometimes the species are differentiated: Amherstia nobilis is known as thawka-gyi (great Ashoka) and Saraca asoca as thawka-bo (male Ashoka).25 Ashoka trees are regarded as sacred across a range of South Asian cultures. In both Hindu and Buddhist traditions, they are associated with female spirits or yakshis which embody fertility and prosperity. In Buddhist tradition, Mayadevi gave birth to the Buddha while holding on to the branch of a tree often identified as the Ashoka.26 These sacred associations likely account for the joint planting of the two beautiful thawka trees – one regarded as male, the other female – in the vicinity of Buddhist temples.27

In the European context, the monastic setting and Wallich’s assertion that Amherstia nobilis was the most beautiful flowering tree in the world boosted Wallich’s status, flattered the Amherst ladies and enhanced the prestige of East India Company science. Hyperbolic as it was, the claim was often repeated and became accepted in European botanical and horticultural circles. It was swiftly endorsed by the prominent botanist John Lindley, who asserted that ‘The beauty of Dr. Wallich’s Amherstia nobilis … is unequalled in the vegetable kingdom’.28 An anonymous review in The Journal of the Royal Institution (which might have also been authored by John Lindley since he lectured at the Royal Institution) singled out the Amherstia plate for praise, and extravagantly elaborated on the religious association:

The Hindoos offer the flowers at the shrine of Buddha. For splendour of colouring and elegance of form, this plate is unrivalled. It is the high priest of the vegetable world, clothed in an investiture more splendid than that of the most gorgeous religion of mankind.29

With its confused references to both Hinduism and Buddhism, the plant here seems to embody Eastern religion, transformed into a flamboyant, orientalised ‘high priest of the vegetable world’. Carelessly amalgamating Asian religions, the passage evokes the shared sacred associations of Ashoka trees in both Hindu and Buddhist traditions. In European popular scientific circles, the tree itself acquired semi-sacred status. In 1838, the Gardeners’ Magazine called Amherstia nobilis ‘that inconceivably splendid tree … to see which, growing in all its native luxuriance, is really almost worth a pilgrimage to the East’.30

Wallich’s inability to locate the tree in the wild, for all that it frustrated the aims of the botanical survey, served to enhance both his own and the tree’s reputation. Amherstia nobilis knew no other home than that of the temple garden. Amherstia nobilis was both sacred and feminised. ‘Its flowers adorn the altars of the god of the Birmans. Its name recalls the graces united with science [the two Amherst ladies]’, declared the French botanist Jules Emile Planchon. ‘Its whole history is in unison with the grandeur and beauty of its attractions.’31 The narrative of the plant was as spectacular as the plant itself. The celebration of the tree’s beauty – its ornamental uselessness – was in striking contrast to the British preoccupation with Burma’s useful trees, notably teak, which were extracted on enormous scale. In a sense, Amherstia nobilis served as a dazzling distraction from the business of deforestation.

Cultivating Amherstia nobilis

Wallich not only publicised Amherstia nobilis in print, but also cultivated a fine specimen at the Calcutta Botanic Garden. Since Amherstia nobilis rarely sets seeds, and those few are often not viable, Wallich obtained layers from the monastery tree. The process of air layering involved wounding the stem, wrapping it with damp moss to encourage rooting, then separating the layer from the plant. The Calcutta tree was the object of Wallich’s particular care. In a later reminiscence celebrating the tree’s incomparable beauty, a British horticultural journalist recalled visiting the tree in Wallich’s company:

well do we remember the sparkling eye and hilarity of Dr. Wallich as he brought us into the presence of his pet tree. He had had a wooden palisading formed round it to prevent visitors gathering its flowers, and well did the tree merit such care. It was in full bloom, and as the breeze from across the Ganges waved the light pendulous branches, the gentle motions and blendings of the crimson racemes and the long pinnate leaves, rendered it the most brilliant and graceful tree we have ever looked upon.32

Wallich, it was said, had marked out a plot under his pet tree, where he might be buried.33

Wallich brought a couple of young Amherstia nobilis plants with him on his London trip in 1828, but both died during the voyage. This misfortune only served to sharpen the acquisitive urge of British horticulturalists. ‘Ever since the publication of the plant in Dr Wallich’s noble work, the Plantae Asiaticae Rariores’, observed Sir William Hooker, first director of Kew Gardens, ‘the greatest desire has been felt by cultivators to possess it’.34 In 1836, the 6th Duke of Devonshire, the most lavish of horticultural patrons, and his famously talented gardener, Joseph Paxton, set their sights on a specimen for Chatsworth. Amherstia nobilis headed the list for the under-gardener, John Gibson, sent on an orchid-collecting trip to India and Burma. In the event, Gibson never reached Burma, but Wallich provided two Amherstia nobilis layers from his pet tree in Calcutta. Planted in a sealed glass Wardian case, one of the layers survived the voyage. At Chatsworth, Paxton lavished attention on the young tree. It was planted in a ‘kyanized’ tub (treated with a newly patented preservative) and grew well. But, for decades, the tree refused to flower. ‘All the amateurs … are in agonies to see this plant bloom!’ an American journalist who visited Chatsworth in 1847 exclaimed.35

For years, the Chatsworth tree was the only living specimen in Europe. The Duke guarded his prize jealously. On hearing that Amherstia nobilis was advertised for sale by a London nursery, the Duke requested that Lindley investigate. ‘No, No, No, My Lord’, Lindley jovially replied, ‘there is no Amherstia in the King’s Road’. The plant was Brownea grandiceps, an imposter with a far less elevated pedigree. ‘Instead of deriving his origin from the Temple Gardens of Buddha’, the Brownea grandiceps had ‘no more dignified birthplace than the bush round a Demerara sugar plantation’.36 By associating Brownea grandiceps with a sugar plantation and its formerly enslaved workforce, Lindley loaded the plant with racial and cultural contempt. By contrast, Amhsertia nobilis appeared ever more exotic, mystical and exalted.

It was Louisa Lawrence, skilled horticulturalist and wife of the surgeon William Lawrence, who was the first to flower Amherstia nobilis in Britain. Lawrence acquired a specimen from Henry Hardinge, the Governor-General of India, and placed it in her glasshouse at Ealing Park (now in west London). Using fermenting tan-bark to heat the tub, Lawrence’s gardeners coaxed the tree into bloom in 1849. Lawrence offered the first raceme to Queen Victoria; a patriotic and imperial gesture that evoked the Burmese presentation of flowers at Buddhist shrines. The second she sent to William Hooker at Kew, who had his resident artist Walter Hood Fitch make ‘an atlas-folio drawing’ of it, ‘a size which can alone do justice to such a subject’.37 This drawing of Amherstia nobilis, ‘perhaps the most beautiful tree in nature’, together with dried flowers and seed pod, was placed on display at Kew’s Museum of Economic Botany.38 Fitch also prepared a smaller lithograph for Curtis’s Botanical Magazine. (See Figure 6.)

+Tab+4453.+RBG,+Kew.++++_copia.png)

Figure 6.

Amherstia nobilis, hand-coloured lithograph by Walter Hood Fitch, Curtis’s Botanical Magazine 75 (1849). Tab 4453. RBG Kew.

Lawrence won medals for Amherstia nobilis flowers at successive Horticultural Society shows. A wax model of the flower, made by Miss Tayspill, was shown at the Pharmaceutical Society in 1850 and another, created by Emily Temple, was displayed at the Great Exhibition the following year.39 The gardening press described Lawrence’s method of cultivation and bulletins tracked the progress of the blooms (on 15 April 1851, for instance, the fourteen-foot tree had been flowering since Christmas day, and had 43 flower spikes).40 Lawrence’s achievement, according to Planchon, was ‘one of the greatest triumphs which Horticulture has for some years inscribed on her annals’.41

News of Lawrence’s success even reached Burma. In the Natural Productions of Burmah (1850), the American Baptist missionary, translator and naturalist, the Rev. Francis Mason, commented wryly that in Britain ‘every tree is said to be worth fifty pounds. When one flowers, it produces quite a sensation from the Thames to the Tweed’.42 With his linguistic skills, Mason identified that Amherstia nobilis and Saraca asoca were both thawka trees, and that Amherstia nobilis was considered female and Saraca asoca male.43 In an appended poem, Mason’s wife, the missionary Ellen Huntley Bullard Mason, elaborated on the feminized thwka-gyi by personifying the tree as ‘a beautiful bride’, veiled in scarlet and gold, ‘The Queen of proud Ava’s wild bower’, outshining the entire British flora: ‘Nor all the rich flowers/ Of Albion’s bowers/ Can vie with its purpling shade’.44 Mason, who regarded natural history as part of his missionary work, concluded the account with the tree’s name printed in Karen script.

In 1854, the year before her death, Louisa Lawrence donated the Amherstia nobilis specimen to Kew and William Hooker renamed one of the glasshouses, Amherstia House in its honour.45 The fashion for Amherstia nobilis spread amongst wealthy horticulturalists in Britain. For instance, at Harewood House in Yorkshire, the seat of the Lascelles family whose wealth had derived from West Indian plantations worked by enslaved labour, the Earl of Harewood erected an Amherstia House and cultivated the tree from 1858.46

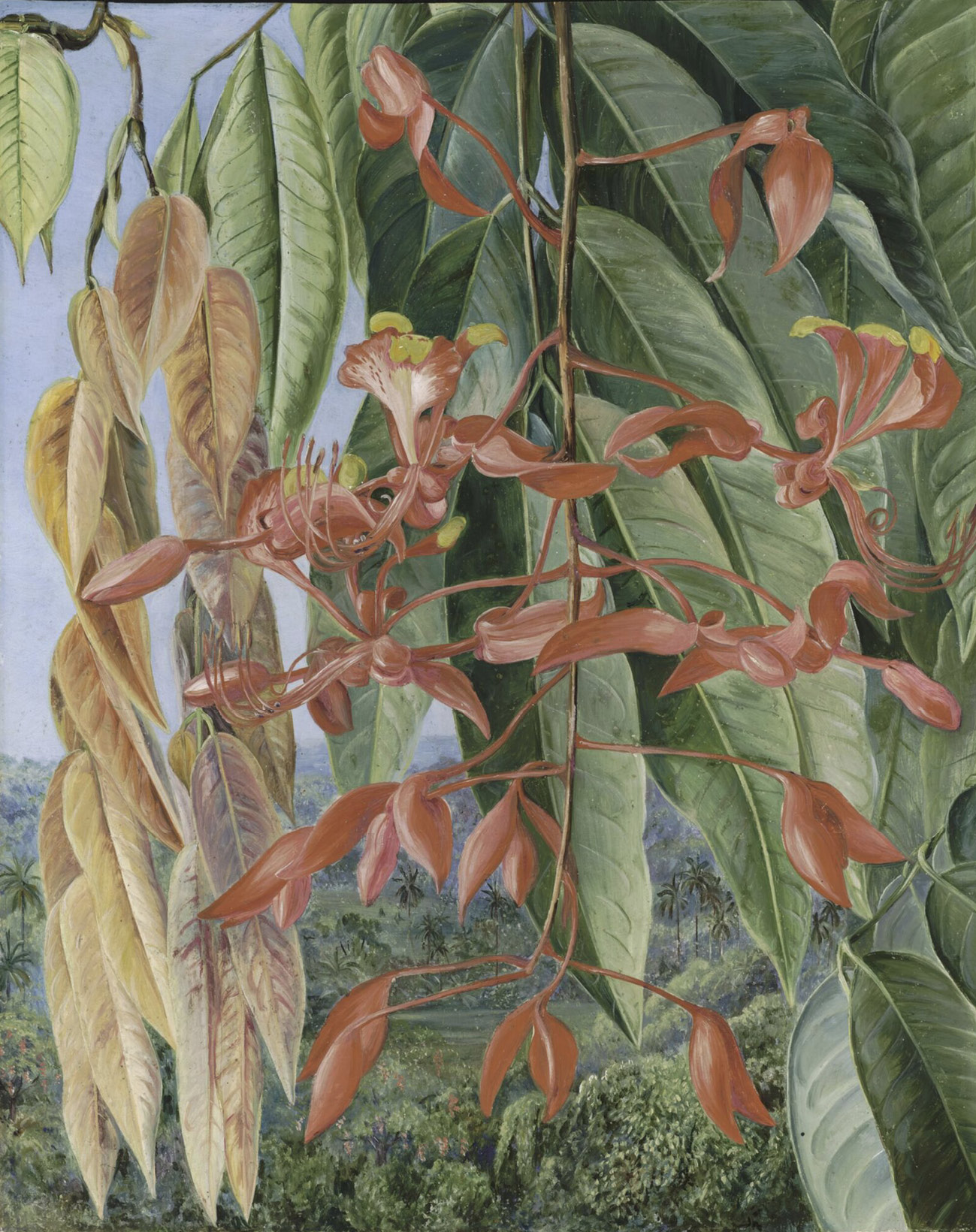

Figure 7.

Marianne North, Amherstia nobilis, North Gallery, MN594. RBG Kew.

Through Kew’s links with colonial botanic gardens, Amherstia nobilis plants were distributed around the globe – to Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Singapore, Jamaica and Trinidad – where they flourished. Hooker considered Amherstia nobilis the arboreal counterpart to the other great botanical sensation of the period, Victoria regia, the giant waterlily, which was first flowered to huge acclaim by Joseph Paxton at Chatsworth in 1849 and later distributed by Kew to colonial gardens around the world. If the Victoria regia ‘bears the most splendid flower of all herbaceous plants, so does this of a Tree’, Hooker wrote in the 1849 edition of his guidebook to Kew Gardens. 47 The flowering of the Amherstia nobilis at Castleton Botanic Gardens in Jamaica was commemorated in the garden’s annual report: ‘One of the most superbly beautiful of trees … the Amherstia nobilis, was in magnificent flower this year, and was worth crossing the globe to see’.48

The year after Amherstia nobilis arrived at Kew, it bloomed. The artist Marianne North, then in her mid-twenties, was in the habit of visiting the Gardens with her father, the Liberal M.P. Frederick North, who was a friend of the director. As North recalled in her memoirs,

once when there, Sir William Hooker gave me a hanging bunch of Amherstia nobilis, one of the grandest flowers in existence. It was the first that had bloomed in England, and made me long more and more to see the tropics.49

According to her autobiographical framing of the incident, the presentation of the exotic flower ignited the young Marianne North’s desire to travel and sparked her subsequent career as botanical painter. Hooker had evidently given North a garbled account of the tree’s religious significance. Travelling from Singapore years later, North encountered the Sanskrit scholar, Arthur Burnell, who ‘contradicted’ her ‘flatly’ when she ‘talked of Amhertstia nobilis as a sacred plant of the Hindus’, as Hooker had informed her.50 Given the symbolic role assigned to Amherstia nobilis in North’s autobiographical account, it is not surprising that the plant should feature in the extraordinary gallery of North’s paintings at Kew. Among the 830 portraits of plants that line the walls of the gallery, no. 594 depicts the ‘Foliage and Flowers of the Burmese Thaw-ka or Soka, painted at Singapore’.51

For the writer, Anne Isabella Thackeray, Amherstia nobilis also functioned as an emblem. It was not a personal symbol, as with North, but rather an allegorical device. ‘The New Flower’ (1866), first published anonymously in the Pall Mall Gazette, was a satirical fairy tale, perhaps modelled on The Rose and the Ring (1855) by her father, William Makepeace Thackeray. The plot of ‘The New Flower’ was based on an 1866 Royal Horticultural Society lecture delivered by the renowned orchid grower, James Bateman, on the unexpected flowering of the Chatsworth Amherstia nobilis after thirty years.

Like North, Bateman endowed Amherstia nobilis with autobiographical significance. He recalled, as a boy, reading a newspaper report that ‘a wonderful flower had been discovered’, then, as a student at Oxford, unexpectedly encountering the same plant as the first plate of Plantae Asiaticae Rariores. ‘Little did he then think that forty years afterwards he should have been called to speak of that very plant’.52 The cause of the tree’s non-flowering, Bateman declared, was the kyanized tub in which it had been planted. The mercuric chloride used as timber preservative had damaged the tree’s health. Once re-potted, the tree flourished and finally flowered. The talk was illustrated with the lithographs from Plantae Asiaticae Rariores, Fitch’s illustration and a splendid raceme from the plant itself. At the end of the meeting, in a reprise of the Burmese ritual, the members resolved to present the raceme to Lady Sarah Williams (née Amherst), the younger of the two Amherst ladies honoured by Wallich in the tree’s botanical name.53

Thackeray refashioned Bateman’s lecture as a fairytale about wealth and privilege. There ‘was once a prince with a beautiful glass palace of his own’, full of the loveliest plants, who was discontented because he had learnt from travellers of a tree ‘more beautiful than anything he had in all his palace which it was almost impossible to procure’.54 Eager to possess the fabled tree, the prince sent a mission to a faraway land to find a monastery garden and the tree whose flowers were offered to images of Buddha. A special tub was prepared which would never rot or decay. When the mission returned in triumph, the tree was planted with great pomp, but for many years, it never flowered. Finally, the expensive pot was identified as the problem. Once replanted in a common tub, the tree started to flourish.

At the end of the story, Thackeray slipped out of fairytale mode to name the protagonists and suggest a political reading of the parable. The day that the Amherstia nobilis had burst into flower was the very day that the Liberal Prime Minister, William Gladstone, introduced the first Reform Bill to extend the franchise to working men.55 By couching the Amherstia nobilis narrative as a satirical fairytale, Thackeray identified the elements that made the tree so desirable: its fabulous beauty, inaccessibility, mystical allure and difficulty of cultivation. At the same time, Thackeray skewered the aristocratic privilege, conceit and extravagance of elite horticulture.

The mystery of Amherstia nobilis

For botanists, one of the most tantalising aspects of Amherstia nobilis was the question of its origins. For nearly two centuries, naturalists tried to locate specimens growing in the wild. In 1830, Wallich had complained that he could not ‘procure the slightest additional information concerning the tree’.56 He surmised that the tree belonged to the forests of the province. In 1858, the Rev. Charles Parish, East India Company chaplain and botanist, returned to the site of Wallich’s early encounter with Amherstia nobilis. He too asserted that the tree was ‘not known to grow wild, nor can the Burmese themselves tell you whence it came originally. They only know that it has been cultivated for very many years by their Pongees or priests’.57 Parish conjectured that the tree originated either in the western provinces of China or the more northern reaches of the river Salween, and that the seeds either floated or were transported downstream.

Six years later, Parish reported confirmation of his river hypothesis. On a boat trip down the river Yoonzalin (Yunzalin), a tributary of the Salween, Parish caught a fleeting glimpse of a single tree. It was in the heat of the day, and Parish had been lying down under cover, when he ‘noticed unexpectedly, on the bank of the river, in one of the wildest spots, a fine Amherstia in full flower, about 30 feet high’.58 Unfortunately for Parish, his sighting was uncorroborated by a fellow European. His military companion, Captain Harrison, was travelling in another boat far behind, and ‘did not notice it, because, not caring for the character of the vegetation, he did not look out from the boat at all’.59

Despite the dream-like quality of the episode, Parish was convinced that he was the first Westerner to see Amherstia nobilis in the wild. It could not have been a cultivated specimen, Parish argued, because the tree was always found in the vicinity of Buddhist temples. This spot was distant from any signs of settlement, and the indigenous Karen people were not Buddhist. In making his assertion, Parish diminished Wallich’s claim to botanical ‘discovery’. In a footnote, Parish somewhat pointedly revised his choice of verb: ‘Wallich discovered it, i.e. first saw it, at a place called Pagât some twenty or thirty miles up the Salween … The trees which he saw are still there … and are manifestly planted trees’.60 To Parish alone fell the glory of having located the tree in the wild. But his fellow cleric, the Rev. Francis Mason, was unconvinced. In an 1876 article published in The Garden, two years after Mason’s death, it was reported that the late Rev. Mason, ‘the best authority on the subject’, had disputed Parish’s assertion. Given that neither the local Karen nor the Shan people recognised the tree, Mason maintained that ‘the home of the Amherstia was still a mystery’.61

The tree continues to be enigmatic to this day. ‘Clearly, this is one of those plants that will remain a mystery’, reflected Benedict Lyte in a 2003 article in Curtis’s Botanical Magazine. ‘There have been no confirmed sightings in the wild since the reports by Reverend Parish’. 62 For Lyte, the narrative of Amherstia nobilis serves as a reminder of the importance of recording accurate information about plants and their precise location. In an encouraging recent development, however, a 2016 survey by the Biodiversity and Nature Conservation Association (BANCA) of the small Kelatha Wildlife Sanctuary in Mon State, Myanmar, found the thawka-gyi growing in a forest area.63 The BANCA 2019 annual report listed 22 individual trees at the site.64

In recent years, thawka-gyi has been the focus of projects in Myanmar to raise community awareness and encourage its cultivation. In 2008–2009, for instance, a community education campaign involved the planting of over 400 saplings around Yangon.65 As David Sayers reported in 2014, trees are available for sale in nurseries.66 In India, R.K. Roy published a 2009 article, ‘Save these rare ornamental trees’, which highlighted the plight of surviving specimens of Amherstia nobilis in Indian historic botanical gardens.67 The tree continues to be cultivated in tropical gardens across the globe, and under glass in European botanic gardens, including Kew. Despite the 22 individual trees identified in the Kelatha report, the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species currently still lists Amherstia nobilis as Extinct in the Wild.68 Unusually, the plant’s status appears essentially unchanged since the nineteenth century.

Conclusion

In tracing the cultural history of thawka-gyi or Amherstia nobilis, this article has recovered the nineteenth-century story of the ultimate ornamental tree. Its history is closely linked to that of British colonial expansion and extraction. From the earliest reports, Amherstia nobilis was claimed as the world’s most beautiful flowering tree, a botanical prize worthy of Britain’s imperial ambition. The tree’s renown was built through spectacular lithographs based on Indian botanical painting and the work of British women in horticulture, literature and art. The nineteenth-century reputation of the tree is perpetuated to this day in the tree’s English popular names: ‘Pride of Burma’ and ‘Queen of Flowering Trees’. Initially sighted in the grounds of a Buddhist temple, the tree’s wild origins remained obscure. The tree’s rarity and sacred association heightened its appeal in Europe. But today, the history of Amherstia nobilis carries a particular resonance. The narrative of a tree known only in gardens foreshadows our current state of nature emergency where some species survive only in cultivated form. At the very moment of first encounter, Amherstia nobilis was already lost.

Acknowledgements

All images are ©The Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. I am grateful to Julia Buckley and Andrew Vymeris for sourcing the images and to Fiona Ainsworth for granting permission to reproduce them.

Many thanks to Kate Armstrong, Jason Carbine, Felix Driver, Christoph Emmrich, Henry Noltie and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. I am also grateful to Henry Noltie for kindly sharing email communication with Trevor Nicholson and the MS of his forthcoming Flora Indica: Recovering Lost Stories from Kew’s Indian Drawings, published to accompany an exhibition which he and Sita Reddy are curating at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew in October 2025.

Kate Teltscher is a cultural historian and writer. She is working on the history of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Her most recent book is Palace of Palms: Tropical Dreams and the Making of Kew (Picador, 2020). She the author of India Inscribed: European and British Writing on India 1600–1800 (Oxford University Press, 1997); and The High Road to China: George Bogle, the Panchen Lama and the First British Expedition to Tibet (Bloomsbury, 2007). She is an Emeritus Fellow at the University of Roehampton, an Honorary Research Associate at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society.

Email: k.teltscher@kew.org

1 Thawka-gyi is written သော်ကကြီး and pronounced ‘thaw-kaar-jee’. It is also sometimes called thawka or athawka. My thanks to Christoph Emmrich for linguistic assistance.

2 J. Crawfurd, Journal of an Embassy from the Governor General of India to the Court of Ava, 2 vols (London: Henry Colburn, 1834), vol. 2, p. 77.

3 ‘Pride of Burma’, International Union for the Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species, assessed 2023: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/226776565/227965606 (accessed 15 December 2024).

4 Previous discussions include D. Arnold, ‘Plant capitalism and company science: The Indian career of Nathaniel Wallich’, Modern Asian Studies 42 (5) (2008): 899–928, at 921; S. Sivasundaram, ‘The oils of Empire’, in H. Curry, N. Jardine, J. Secord and E. Spary (eds), Worlds of Natural History, pp. 379–98 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), pp. 387–88; K. Colquhoun, The Busiest Man in England: A Life of Joseph Paxton (Boston: David T. Godine, 2006), pp. 67, 70–72.

5 K. Raj, Relocating Modern Science: Circulation and the Construction of Knowledge in South Asia and Europe, 1650–1900 (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2007); H. Noltie Robert Wight and the Botanical Drawings of Rungiah and Govindoo, 3 vols (Edinburgh: Royal Botanic Gardens, Edinburgh, 2007); Noltie, Botanical Art from India: The Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh Collection (Edinburgh: Royal Botanic Gardens, Edinburgh, 2017); Noltie, Flora Indica: Recovering Lost Stories from Kew’s Indian Drawings (London: Kew Publishing, 2025).

6 G.E.B., ‘The Amherstia nobilis in India’, The Garden 9 (1876): 209.

7 See A. Shteir, Cultivating Women, Cultivating Science: Flora’s Daughters and Botany in England, 1760–1860 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996); A. Shteir and B. Lightman (eds), Figuring it Out: Science, Gender, and Visual Culture (Hanover, New Hampshire: Dartmouth College Press, 2006); B. Gates, Kindred Nature: Victorian and Edwardian Women Embrace the Living World (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1999); Gates, ‘“Those who drew and those who wrote”: Women and Victorian popular science illustration’, in Shteir and Lightman (eds), Figuring it Out; S. Le-May Sheffield Revealing New Worlds: Three Women Naturalists (London: Routledge, 2001); N. Johnson, Empire, Gender, and Bio-geography: Charlotte Wheeler-Cuffe and Colonial Burma (Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2024).

8 Nineteenth-century plant collection was even practised during military campaigns – see for example William Griffith’s activities during First Anglo-Afghan War (1838–42): L. Fleetwood, ‘Science and war at the limit of empire: William Griffith with the Army of the Indus’, Notes and Records 75 (2021): 285–310.

9 H. Falconer, Report on the Teak Forests of the Tenasserim Provinces (Calcutta: Military Orphan Press, 1852), p. 82.

10 R.L. Bryant, The Political Ecology of Forestry in Burma (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1997), pp. 32–36.

11 H. Noltie and M. Watson, The Collectors of the Wallich (or East India Company) Herbarium. Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh (2021): https://stories.rbge.org.uk/archives/34728 (accessed 11 December 2024).

12 ‘Linnaean Society’, The Philosophical Magazine 3 (1828): 223.

13 D. Arnold, ‘Plant capitalism and company science’.

14 Noltie, Flora Indica.

15 N. Wallich, Plantae Asiaticae Rariores, 3 vols (London: Treuttel & Würtz, 1830–32), vol. 1, pp. 13–15. Indian subscribers included members of the Calcutta intellectual and merchant elite: Dwarkanath Tagore (1794–1846), Ramkamal Sen (1783–1844), Prasanna Kumar Tagore (1801–86) and Radhacanta Deb (1784–1867).

16 H.R.H., ‘The Botanical periodicals and their illustrations’, Gardeners’ Magazine 4 (1838): 171–76, at 172.

17 Wallich, Plantae Asiaticae Rariores, vol. 1, p. 2.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 Sivasundaram, ‘The oils of Empire’, p. 388.

21 Wallich, Plantae Asiaticae Rariores, vol. 1, p. 2.

22 A. Khazeni, The City and the Wilderness: Indo-Persian Encounters in Southeast Asia (Oakland: University of California Press, 2020), pp. 66–68.

23 Wallich Plantae Asiaticae Rariores, vol. 1, pp. 2–3.

24 Thawka is sometimes also called athawka – see A.M. Sawyer and D. Nyun, A Classified List of the Plants of Burma (Rangoon: Government Print and Stationery, 1927), p. 49; F. Mason, The Natural Productions of Burmah (Maulmain: American Mission Press, 1850), Preface.

25 ‘Sorting Saraca Names’, Multilingual Multiscript Plant Name Database: https://www.plantnames.unimelb.edu.au/Sorting/Saraca.html (accessed 6 Feb. 2025); Mason, Natural Productions of Burmah, Preface.

26 B. Bidari, ‘Forest and trees associated with Lord Buddha’, Ancient Nepal 139 (1996): 11–24, at 15–16.

27 Mason, Natural Productions of Burmah, Preface.

28 J. Lindley, Introduction to the Natural System of Botany (London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green, 1830), p. 90.

29 ‘On the Botany of India’, The Journal of the Royal Institution of Great Britain 1 (1831): 360–67, at 364.

30 H.R.H., ‘The Botanical periodicals’, 173.

31 ‘Amherstia Nobilis’, Philadelphia Florist (1853): 203–04, at 204.

32 ‘Scientific Meeting’, The Journal of Horticulture, Cottage Gardener and Country Gentleman 35 (1866): 240–41, at 241.

33 Obituary Notice: ‘Nathaniel Wallich’, The Cottage Gardener 12 (1854): 91–92, at 91.

34 ‘Amherstia nobilis’, Curtis’s Botanical Magazine 75 (1849): Tab 4453.

35 ‘Impressions of Chatsworth’, The Horticulturalist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 1 (1847): 297–302, at 301.

36 ‘A Great Gardener-Architect’, Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society 59 (1934): 477–81, at 479.

37 ‘Amherstia nobilis’ (1849): Tab. 4453.

38 W.J. Hooker, Museum of Economic Botany: Or, a Popular Guide to the Useful and Remarkable Vegetable Products of the Museum of the Royal Gardens of Kew (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1855), p. 38.

39 ‘The Conversazione’, Pharmaceutical Journal and Transactions 9 (1849–50): 551–52, at 551; ‘Official Illustrated Catalogue Advertiser’, in Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue of the Great Exhibition 1851, vol 1. (London: Spicer Brothers, 1851), p. 26.

40 ‘Garden Memoranda’, Gardeners’ Chronicle and Agricultural Gazette 231 (1851): 231.

41 ‘Amherstia Nobilis’ (1853), 204.

42 Mason Natural Productions of Burmah, pp. 61–62.

43 Ibid.: Preface.

44 Ibid.: 62.

45 The tree was transferred to the Palm House after three years, but died following the move, R. Desmond The History of the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, 2nd ed. (Kew: Kew Publishing, 2007), p. 180.

46 Email communication from Trevor Nicholson and Henry Noltie, 15 May 2025.

47 Hooker, Kew Gardens, p. 32.

48 ‘Miscellaneous Notes’, Bulletin of Miscellaneous Information 63 (1892): 71–76, at 74.

49 M. North, Recollections of a Happy Life, 2 vols (London: Macmillan, 1894), vol. 1, p. 31.

50 Ibid., vol. 1, p. 252.

51 Official Guide to the North Gallery, 5th ed. (London: HMSO, 1892), p. 92.

52 ‘Scientific Meeting’, 240.

53 Ibid., 240–41.

54 A. Thackeray, ‘The New Flower’, in Toilers and Spinsters, and Other Essays, pp. 230–35 (London: Smith, Elder & Co, 1874), p. 230.

55 Ibid., p. 232.

56 Wallich, Plantae Asiaticae Rariores, vol. 1, p. 2.

57 ‘Extract from a Letter to Sir Wm. Hooker from C.S. Parish’, Gardeners’ Chronicle 174 (1858): 174.

58 C. Parish, ‘Notes of a trip up the Salween’, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 34 (3) (1865): 135–46, at 145.

59 Ibid.

60 Ibid., 146.

61 G.E.B., ‘The Amherstia nobilis in India’. The Garden 9 (1876): 209.

62 B. Lyte, ‘Amherstia nobilis: Plants in Peril 28’, Curtis’s Botanical Magazine 20 (3) (2003): 172–76, at 174.

63 BANCA, ‘A case study of ecosystem services rendered by Kelatha Wildlife Sanctuary for the local communities’, Yangon: Biodiversity & Nature Conservation Association (2016), p. 19: https://cdn.digitalagencybangkok.com/file/client-cdn/banca/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/a-case-study-of-ecosystem-services-rendered-by-kelatha-wildlife-sanctuary-for-the-local-communities.pdf (accessed 17 December 2024).

64 BANCA, ‘Annual Report 2019, Yangon: Biodiversity & Nature Conservation Association (2019), p. 24: https://cdn.digitalagencybangkok.com/file/client-cdn/banca/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/annual-report.pdf (accessed 17 December 2024).

65 Rufford Foundation, ‘Initiation of Community Conservation Efforts in Myanmar with focus on endemic Queen of Flowering Tree’ (2008): https://www.rufford.org/projects/khun-bala/initiation-of-community-conservation-efforts-in-myanmar-with-focus-on-endemic-queen-of-flowering-tree-pride-of-myanmar/ (accessed 15 December 2024).

66 D. Sayers, ‘Tree nurseries in Myanmar’, International Dendrology Society, Yearbook 2014: 38–40, at p. 40: https://www.dendrology.org/publications/dendrology/tree-nurseries-in-myanmar/ (accessed 19 December 2024).

67 R.K. Roy, ‘Save these rare ornamental trees’, Current Science 97 (2009): 1536–38, at 1537.

68 ‘Pride of Burma’, IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.